I n May 2017, Jean-Michel Basquiat' s painting, Untitled (1982), sold to Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa for $110.5 million at Sotheby's in New York – the fifth-highest price ever paid for an art work at auction.

In many ways, this was a breathtaking result; only Picasso, Modigliani, Bacon and Munch had produced pieces more lucrative. On the other hand, it was simply confirmation of a tendency that has long been evident: that the late New Yorker – who evolved from graffiti on the streets of Lower Manhattan to Neo-Expressionist canvases – is the hottest property in art right now.

His works are collected by the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio and Johnny Depp. The clothing company Uniqlo and footwear company Reebok have reproduced Basquiat's imagery – on their T-shirts and trainers respectively. Hip hop artists such as Kanye West and Jay-Z have rapped about him, the latter going so far as to proclaim himself “the new Jean-Michel” in his 2013 song, Picasso Baby.

There have also been recent blockbuster exhibitions in major cities, including Paris, Toronto and Rio de Janeiro. Finally, this autumn, London sees its first ever Basquiat retrospective too: Boom for Real, at the Barbican Centre.

How are we to explain the immense popularity, though? Yes, Basquiat was a star in his own lifetime – renowned for painting in Armani suits, dating Madonna and hanging out with Andy Warhol – but the current adulation is on another level. In part, it's a product of the myth that has built up around Basquiat since his death from a drug overdose in 1988.

Roughly told, the myth involves his running away from an abusive father to live on the streets, where he started making the much-noticed graffiti art that would launch his career. He'd go on to produce a succession of brilliant paintings in the space of a few years, before his untimely death, aged 27.

Like Van Gogh, he was active for an intense, solitary decade – and the nagging sense persists of what might have been, had he survived. Perhaps not a lot, but the fascination with Basquiat – as with so many artists who die young – is that, tantalisingly, we'll never know.

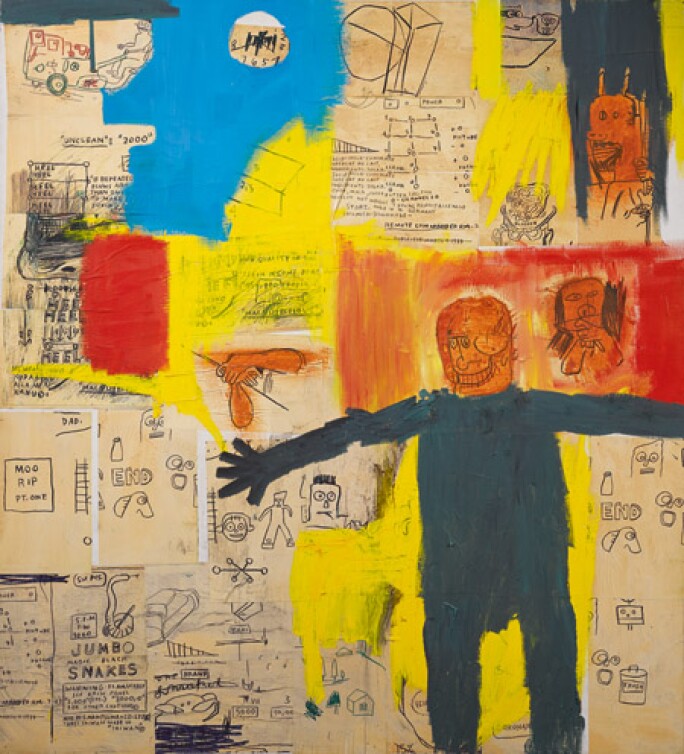

Then there are his roots in street art – and the way a street aesthetic (scrawled text, stick figures, obscure symbols and striking colours) even pervaded his canvases. Where once it was considered an illegal eyesore, fast forward a few decades and street art now has a strong case for being the most important artistic movement of the 21st Century.

From São Paolo to Sydney, it's reclaiming and redefining urban spaces everywhere. To coincide with Boom for Real, one of its leading practitioners, Banksy, has even painted two works in homage to Basquiat on the walls of a tunnel outside the Barbican. A work by Banksy is also offered for sale in the Contemporary Art Evening Auction.

Another factor to consider is that Basquiat tried his hand at a number of art forms other than his own (music, most notably) – which has meant he's remembered, and cited as an influence, beyond just the art world. In his early days, he played in a post-punk band called Gray in underground New York venues, for instance; while in 1983, he produced the classic hip-hop single Beat Bop for Rammellzee and K-Rob.

Basquiat certainly didn't see why being an artist should mean permanently being stuck with a paintbrush in your hand. This open-minded attitude points to a further way that he heralded the 21st-Century: what the Barbican curators, Dieter Buchhart and Eleanor Nairne, call his 'interdisciplinarity'. In other words, the way he drew on an array of different source material for his paintings. These sources ranged from cornflake packaging and Beat poetry to Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings – and, in the case of Remote Commander (1984), also offered for sale on October 5, the volume and picture-quality settings on a TV remote control.

The curators suggest that: "by sampling from everything he perceived", he anticipated the way we all consume information on the internet and the free-associative hodgepodge that is our browser history at the end of each day.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, then, is in tune with a host of 2017's cultural trends. It's too much a stretch to say he inspired them all, of course – but one could surely argue that he was ahead of his time and the rest of the world is merely now catching up. Almost 30 years since his passing, Basquiat – culturally speaking – has never been more alive.