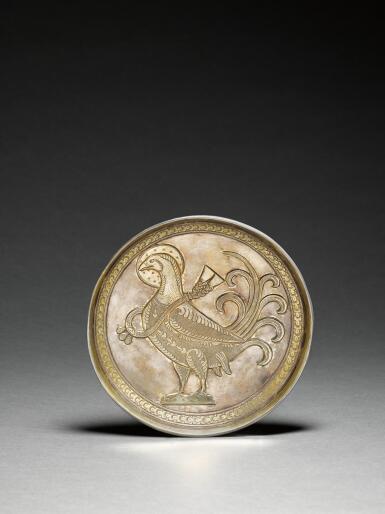

An early Islamic or post-Sassanian silver gilt dish depicting a bird, Persia, 6th-8th century

Auction Closed

April 30, 03:48 PM GMT

Estimate

100,000 - 150,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

of shallow rounded form on a short foot, with a large nimbate bird standing in profile wearing a diadem with 3 drop pendants around the neck, within a frieze of lobed motifs, the foot with stippled inscription, with stand

21.5cm. diam.

Ex-collection Kojiro Ishiguro (1916-92), Japan, pre-1960s, by repute

Ex-private collection, UK, 1960s

David Aaron Ltd., London, 2017

Ex-Wyvern Collection, acquired 25 May 2017, inv. no.2411

Acquired by the present owner, 2023

Epic Iran: 5000 Years of Culture, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 13 February- 13 August 2021

M. Aimone, The Wyvern Collection, Byzantine and Sasanian Silver, Enamels and Works of Art, London and New York, 2020, pp.224-6, no.60

J. Curtis, I. Sarikhani Sandmann, and T. Stanley, Epic Iran: 5000 Years of Culture, London, 2021, p.128

The wonderfully preserved plate, exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum’s major exhibition on Persian art, depicts a handsome bird emblematic of Sassanian dynastic iconography. It can be situated within a period of continuation of such imagery following the Umayyad conquest of the Sassanian empire.

The nimbate bird on this plate stands proudly and is embellished with imagery perpetuating the iconography of Sassanian royalty long after its political demise: a garland with three drop pendants, and a beaded halo. This iconography was not confined to metalwork but can be found on textile; see a silk shirt with a repeat pattern of standing pheasants sold in these rooms, 4 October 2011, lot 11, and another textile from the Jouarre Abbey collection, Seine-et-Marne, France (Epic Iran: 5000 years of culture, London, 2021, no.110). Comparable representations are found in fresco fragments from the Qyzil monastery in Chinese Turkestan, now in The Hermitage, St Petersburg, and the Museum für Indische Kunst, Berlin (illustrated in Beurdeley, 1985, p.117, no.117).

The chronology of works typically labelled as post-Sassanian has been challenged by Julian Raby in a recent study on an Umayyad buck, sold in these rooms, 23 October 2024, lot 122. He notes that this dynastic periodisation assumes that stylistic changes corresponded with change in rule, thus neglects continuations in craftsmanship and imagery. As a result, there is a relative paucity of objects identifiable as Umayyad, with only few examples bearing identificatory inscriptions, which appears puzzling when considered in relation to their renowned architectural achievements.

The remarkable Dome of the Rock bears testament to the Sassanian influence in Umayyad architecture. Alain George relates forms found within the spandrels of the inner octagon, bejewelled vases with wings, to a type of pre-Islamic crown found on Sassanian coins and metalwork, and later in Umayyad coins (2018, p.40). This usage suggests a conscious effort a “gesture of appropriation, [which] would have been all the more potent in early Islamic Jerusalem, at the hands of the polity that had recently brought about the final demise of the Sasanians” (George, op.cit., p.43). On a practical level, Sassanian artists now working under the Umayyads would also be working in their habitual repertoire.

Indeed, the three-pendant necklace, mentioned above, also figures on Umayyad coins issued by the governors of Iran (Aimone 2020, p.225). Watercolours of ninth century Samarra by Ernst Herzfeld further indicate the present of a familiar bird enclosed within a roundel border seen in this plate, and on the above-mentioned silks. One might also relate the stance of the bird to the magnificent animal aquamaniles such as an eagle in the State Hermitage Museum which bears an inscription in Arabic (inv. no.ИР-1567). While the precise chronology of plates such as ours remains to be clarified, it participates at some level within this period of continuation which saw the Umayyads and the ‘Abbasids draw on established Sassanian iconography to construct their own dynastic image.

A dish depicting a simurgh within a comparable frieze of tri-lobed motifs is in the British Museum (inv. no.124095), and another decorated with an archer on horseback was sold in these rooms, 24 April 2013, lot 115.

You May Also Like