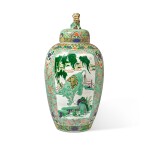

A Large Chinese Green-Ground Famille-Verte 'Animals' Jar and Cover, Qing Dynasty, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

清康熙 綠地五彩開光瑞獸圖大蓋罐

Auction Closed

April 20, 12:24 AM GMT

Estimate

40,000 - 60,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

A Large Chinese Green-Ground Famille-Verte 'Animals' Jar and Cover

Qing Dynasty, Kangxi Period (1662-1722)

清康熙 綠地五彩開光瑞獸圖大蓋罐

(2)

25 in. (63.5 cm.) high

Collection of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (1874-1960), New York

Collection of Vice-President Nelson A. Rockefeller (1908-1979), New York

Collection of Winston F.C. Guest (1906-1982), New York

Ralph M. Chait Galleries, New York

Wolf Family Collection No. 0784 (acquired from the above on February 22, 1985)

Superbly enameled, the present jar and cover represent the quintessence of famille verte decoration. In the 1680s, following the Kangxi Emperor’s (r. 1662-1722) victory over the last of the Ming rebellions, the reestablishment of the kilns at Jingdezhen, damaged during the uprising, was a priority. The Kangxi Emperor was keenly aware of the historic and cultural significance of Chinese porcelain and strove to not only revitalize the kilns but encouraged technical innovations to surpass past achievements, thus conferring prestige to the newly established Qing dynasty. During the Kangxi period, the porcelain clay was refined, producing a silkier, whiter, thinner yet more durable body than seen in late Ming examples.

Furthermore, continuing a practice initiated during the Wanli period, the Kangxi Emperor met regularly with a select group of Jesuit priests within the imperial palace to gain a comprehensive understanding of European advances in astronomy, mathematics, and areas of the arts, glass being of paramount interest. The Emperor requested a specialist be sent from Europe. The German Jesuit Kilian Stumpf, skilled in glassmaking, arrived in 1695 and within months of his arrival had set up a workshop inside the imperial palace. Access to European enamel and glass techniques sparked advances in enameling porcelain. A brighter, glassier, more jewel-toned palette of overglaze enamels was a welcome early byproduct of this cultural exchange. The range of exceptionally lustrous greens inspired the term famille verte, coined in 1862 by the French scholars Albert Jacquemart and Edmond Le Blant to describe the colorful decoration that includes iron red, yellow, aubergine, black, and a new addition, overglaze blue created using European imported smalt. By 1700 famille verte was being produced in Jingdezhen. The tonal ranges of famille verte are skillfully and brilliantly represented on the present jar and cover. The intense depth of the green-enameled tree leaves contrasts effectively with the varying greens of landscapes and the pale green ground. The swirling polychrome clouds illustrate the deft touch of the enamellers to control tone and translucence. The overglaze blue is richly applied to the rockwork and flowers along the base, adding weight and depth to the composition.

The three large reserves painted around the body each contain auspicious animal imagery. One depicts a winged qilin galloping above the ground, its head reared back issuing flame-like vapor. The appearance of a qilin brings good luck and prosperity. The creature defends the just and only appears in an area which is controlled by a wise and benevolent leader. Another depicts an elephant (xiang) which, like so many other examples in Chinese iconography, is a homonym for the word happiness. Elephants, therefore, are associated with good fortune. The contrived interpretation of the animal, with its ample folds of loose skin and large, deep-set eyes, reveals not just an unfamiliarity with actual elephants, but the widespread acceptance of artistically derived imagery with Buddhist associations. The lotus flowers painted on the saddlecloth echo the Buddhist connection. The third mythical animal, a male Buddhist lion, rollicks in the foreground, its head gazing upwards towards a beribboned ball. Famed as protector of Buddha, the Buddhist lion is a symbol of protection and strength.

There appear to be only three other examples of similar jars and covers, and all are in museum collections. Two, from the collection of Augustus the Strong (r. 1670-1733), are in the Zwinger, Dresden (inventory nos. PO 3027 and PO 6323), and the third, which was also formerly in the collection of Augustus the Strong in Dresden, illustrated in Walter Bondy, Kang-Hsi, Munich, 1931, p. 143, and then in the collection of Leonard Gow, illustrated in R. L. Hobson, Catalogue of the Leonard Gow Collection of Chinese Porcelain, London, 1931, pl. XXXII, is currently in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia (accession no. 1955-50-75a,b).

Like much of the porcelain in the Wolf Collection, the present lot boasts a superlative provenance. Peter Ralli was a successful merchant and banker. An avid collector, Ralli begain purchasing fine Chinese porcelains around 1900, many with impressive provenance including pieces from the collections of Sir William Bennett, Alfred Trapnell, and Richard Bennett. He was also drawn to porcelains that had duplicates in Dresden, such as the present piece. For more on Ralli, see Roy Davids and Dominick Jellinek, Provenance: Collectors, Dealers & Scholars: Chinese Ceramics in Britain & America, Oxon, 2011, p. 368. Born into wealth, Winston Guest was a first cousin to Winston Churchill. A client of Ralph M. Chait in New York, Guest collected Qing dynasty porcelain and like, Ralli, sought pieces with strong provenance including porcelains from the collections of Edward R. Bacon, J.P. Morgan and, as in the present lot, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who himself owned pieces from Morgan.

You May Also Like