Pacific Art from the Collection of Harry A. Franklin

Pacific Art from the Collection of Harry A. Franklin

MAORI GABLE FIGURE (TEKOTEKO)

Auction Closed

May 13, 03:32 PM GMT

Estimate

500,000 - 700,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

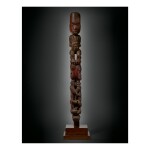

MAORI GABLE FIGURE (TEKOTEKO)

New Zealand, probably Bay of Plenty

Wood, obsidian, pigments

Height: 37 ¾ in (96 cm)

on a base by the Japanese wood artist Kichizô Inagaki (1876-1951), Paris

A MAORI MASTERPIECE

This fascinating and powerful Maori sculpture is a highly distinctive work of individual genius, created by a great Arawa artist from the North Island of New Zealand, who was presumably working in the 18th or very early 19th century at the behest of an important chief.

The majority of major Maori wood sculptures were created to appear as part of culturally important structures, and one of the defining achievements of Maori art is that it combines this practical, architectural purpose with sculpture of the highest order. The magnificent object presented here originally belonged in this context, as a tekoteko, or gable figure, which was placed at the apex of one of the buildings in the marae, the wahi tapu or sacred space of the village. The scale of the present tekoteko suggests that it once adorned a storehouse, or pataka, of the late 18th or early 19th century type, when such buildings were of small size. In the early 19thcentury the small pataka was a distinctive feature of many Maori settlements, and whilst not all had an elaborately carved storehouse, or pataka whakairo, one would certainly be found in any village of consequence. The pataka was the property of the chief and was a sign of his authority and prestige. Elsdon Best notes that "the carved pataka seems to have been an object on which the leading chiefs lavished the best and most skilled labour at their command; and whatever might be the position of the ordinary food and store houses in the marae, a good position was always selected, in full view of the chief's dwelling, for the prized pataka whakairo" [1]. The carved pataka was not used for the storage of common goods, but rather for the most prized foods, such as preserved birds, or huahua manu, and valuable treasures, or taonga, objects rich in mana, such as weapons, fine cloaks, or articles made from precious pounamu, greenstone.

Ancestors, tupuna, are essential to Maori culture and art, and depictions of the human figure – the most important aspect of Maori sculpture – almost invariably depict ancestors [2]. The human image, or tiki, depicted at the top of this tekoteko represents an important male ancestor who stands, as was customary, "upright in full frontal view" [3]. This important ancestor was placed on the pataka to guard the building and its contents, which were tapu, or sacred, and subject to many prohibitions. As with all Maori ancestor images, the head is of the greatest significance, being tapu and the seat of great mana. It is notable here for its elegant, tapered, elongated form, which is characteristic of Arawa sculpture from the Bay of Plenty in the North Island. Its powerful expression conveys the authority and intensity which is characteristic of the best Maori ancestor sculptures, whilst the clarity and purity of its form is redolent of certain God or ancestor images from western Polynesia.

The head of the ancestor figure also draws our attention to another of the most extraordinary and distinctive aspects of this sculpture, which is the use of obsidian, tuhua, or mata-tuhua, for the inlays of the eyes. The tekoteko's concentrated stare is given a special intensity by the deep, dark, gleam of the volcanic glass, capable of both absorbing and reflecting light. Obsidian was much valued by Maori but its use in sculpture is exceptionally rare [4]. It appears to be another indication of the sculpture's Arawa origin since, as the historian James Belich remarks, "the most important early source [of obsidian] was Tuhua, or Mayor Island, in the Bay of Plenty […]" [5], the island from which this precious material derives its Maori name [6].

Whilst ancestor figures were intended to be seen frontally, the present example illustrates that the great Maori sculptors had full command of sculptural depth and understood the use of positive and negative space. Here, the ancestor figure is carved fully in the round, with the torso of characteristic arched form, with a hollowed, concave lower back, and well-defined legs, arms, and hands. The sculptor has created rounded, fully sculptural forms which flow effortlessly from one surface to the other. In contrast with the austere character of the head, the body is adorned with a series of aqueous spirals which lend the hieratic pose a sense of fluidity. These spirals are carved in high relief, bulging away from the surface, in a manner characteristic of early Maori sculpture, when relief carving was far more sculptural than pictorial in character. The hands of the figure are carved in the talon-like three finger style, the significance of which has long attracted speculation [7]. Neich notes that most commentators have come to regard the number of fingers as "a stylistic decision, guided by certain regional preferences and stylistic considerations" [8].

Below the ancestor figure appears another highly distinctive aspect of this tekoteko; the depiction of an "embracing" couple, as this iconographical form is generally referred to in the literature. Neich notes that such figures "placed side by side with their arms about each other are a fairly infrequent motif in the total field of Maori carving [… but] an examination of all the known examples […] soon makes it clear that the motif is distinctively Arawa" [9], providing further evidence for the Arawa attribution. We may note that this rare iconography is seldom depicted on a tekoteko, and more commonly appeared on carved support posts or panels, amo or poupou. Neich notes that whilst some sculptures "actually show the figures in sexual congress, others simply show the genitalia, while most do not show any sexual organs" [10]. It is to this first and rarest group that the present tekoteko belongs. Here the couple hold each other's necks with one arm, their heads turned away from one another, looking out to left and right. The heads are very similar in form to that of the ancestor figure, and their highly elongated bodies are decorated with similar, deeply carved motifs. The arm of the male clutches the body of the female, whilst her elongated left arm reaches down behind her leg. The deep openwork carving and layered body parts are again characteristic of the highly sculptural, rather than pictorial, quality of this type of early Maori sculpture.

Neich notes that male and female couples depicted in the "embracing" iconography represented "high-ranking ancestors, symbolising the beginning of important new descent lines and at the same time the joining of two antecedent descent lines" [11]. Several early sources attest to the iconography's long history on the North Island. Not intended as erotic in their original context, they nevertheless struck certain prurient European visitors as such. One observer, Richard Cruise, visited the Bay of Islands in 1820, and saw at Waikare a pataka whakairo carved with "indecent figures" [12]. Visual depictions of the iconography also appear at around the same date. Allowing for the stylization common to early nineteenth century illustrations of Polynesian objects, we note that the engraving of a tekoteko (identified simply as "idole") in Jules Dumont d'Urville's Voyage de la corvette l'Astrolabe (see fig. 1) [13], depicts the "embracing" iconography in a manner which closely resembles its appearance here. Presumably that intriguing sculpture, which we have been unable to trace, was seen during the Astrolabe's travel around the North Island in 1827. Amongst other works, similar iconography can be seen in the panels of a pataka depicted in Augustus Earle's watercolour A tabood store-house at Range-hue, Bay of Islands, New Zealand, circa 1827, in the collection of the National Library of Australia, Canberra (Rex Nan Kivell Collection, inv. no. NK12/81).

More interesting than Richard Cruise's brief observation on the iconography of the pataka he saw at Waikare is his description of how such prestigious objects came to be made. Discussing the same pataka, Cruise notes that "the carving is a work of much labour and ingenuity; and artists competent to its execution are rare. Wevere [a Maori chief] pointed out to us the man who was then employed in completing the decorations of his store-house, and told us, that he had brought him from the river Thames [Waihou] (a distance of two hundred miles from the Wycaddy [Waikare]), for that purpose" [14]. This historic information corresponds with the work of later scholars; Deidre Brown, discussing a pare, or door lintel in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, notes that although acquired in the Bay of Islands, it was possibly carved by "Bay of Plenty tohunga whakairo" [15], and Roger Neich observes that "several of the northern storehouses recorded in 1827 in the paintings of Augustus Earle were built by experts from the Bay of Plenty, captured and enslaved by the northern raiders too busy with warfare to build their own" [16].

At the very bottom of the sculpture, beneath the couple, appears a downward-looking head, its mouth open, tongue sticking out in a gesture of challenge. The head retains traces of red ochre, kokowai, which is also visible in other places, along with areas of green pigment. The latter was doubtless applied later in the figure's history, probably to preserve the sculpture – the exposed ancestor figure in particular – against the depredations of the weather. The sigificance the green pigment may have had is not known to us, but it is tempting to draw a link between it and the great prestige accorded to pounamu, or greeenstone. The deep symbolic importance of kokowai, which is made from red ochre mixed with shark-liver oil, is well known. The colour red, kura, could mean a treasure, something precious, or an especially able chief. "As a consequence of this powerful charge of meaning, red paint on carvings [and] chiefly possessions […] marked them as charged with the dangerous power of tapu, to be avoided by common people" [17].

Three Icons: Oldman, Breton, Rubinstein

Beyond its own inherent importance as a major Maori sculpture, this tekoteko is notable for its illustrious provenance, having found favour with three of the most iconic names in the history of collecting. Whilst we have no remaining trace of its original provenance, by the first quarter of the 20th century the tekoteko was in the possession of William Oldman, the legendary dealer and collector, who assembled the greatest ever private collection of Polynesian art [18]. In a photograph taken in Oldman's house, in Clapham, south London (see fig. 2), the tekoteko can be seen alongside other Maori sculptures, some of which were brought to England by Captain James Wilson of the missionary ship Duff in 1798 [19]. Whilst we do not have a precise record of when Oldman acquired the tekoteko, it is likely that he bought it in the United Kingdom, presumably at auction or from the family of the person who first brought it from New Zealand.

By the 1920s the tekoteko was in the collection of André Breton, leader of the Surrealist movement and one of the great collectors of Oceanic art. Breton acquired his first object, an Easter Island sculpture, in 1908, when he was 12 years old [20]. His parents were scandalized. Although his earliest collecting encompassed the African art which was the sine qua non of contemporary taste, his eye turned – or returned – more towards Oceanic art, which for the Surrealists more fully embodied the ideals of their movement. By the 1920s Breton was acquiring objects on trips abroad in the company of his friends Louis Aragon and Paul Eluard. London was a favoured haunt. The guide to the British Museum collections was their bible, and William Oldman's house a place of pilgrimage; Elizabeth Cowling notes that Oldman was "the source of many of the Oceanic pieces in their collections" [21]. Breton himself said that many of these trips were undertaken in "the hope of discovering, at the cost of constant searching from morning to night, some rare Oceanic object" [22].

The exact date at which Breton acquired the tekoteko from Oldman is not known, but in 1929 it was published as belonging to Breton in Henri Clouzot's brief article on Maori art in the special Oceanic art edition of the modernist periodical Cahiers d'art. By 1931, financial difficulties compelled Breton and his friend Paul Eluard to sell their collections. An auction was organized by Charles Ratton. The presentation of the collection has become iconic; as Peltier writes, the cover of the catalogue (see fig. 3) "broke with tradition by its typography and by the substitution of the words 'sculpture from Oceania, Africa, and America' for 'primitive arts', a change that […] sought to introduce these objects into a 'universal museum'" [23]. The tekoteko was bought at the auction by Paul Chadourne on behalf of the legendary collector Helena Rubinstein. Doctor and Dadaist, Chadourne lent objects to the seminal exhibitions at the galerie du théâtre Pigalle in Paris in 1930 and African Negro Art at the Museum of Modern Art in 1935. In the early 1930s he acted as an advisor and intermediary for Rubinstein, buying objects for her at auction, and negotiating her acquisition of the important collection of Bamana and Senufo objects collected by Frédérick Henri Lem [24].

The tekoteko was installed by Rubinstein in her famous apartment at 24 quai de Béthune on the île Saint-Louis in Paris. The apartment was designed by the architect and decorator Louis Süe, and when work finished in 1937 Rubinstein commissioned a series of photographs from Dora Maar, the photographer, painter, and poet. Maar's photograph of the living room (see fig. 4) shows the tekoteko standing sentinel opposite Brancusi's 1928 sculpture Négresse blanche II (now in the Art Institute of Chicago, inv. no. 1966.4). These two sculptures, made more than a hundred years apart in vastly disparate places and contexts, were united by their appeal to one of the twentieth century's great art collectors, and by their shared status as great sculptures, both rich in significance and layers of meaning.

Notes

1 Best, Maori Storehouses and Kindred Structures, Wellington, 1974, p. 13

2 With the exception of the so-called "god sticks", tiki wananga, and occasionally pare, or panels, from important buildings.

3 Neich in Starzecka, ed., Maori Art and Culture, London, 1996, p. 91

4 The inlays are unquestionably original to the sculpture, with the eyesockets having been deeply carved to accommodate them.

5 Belich, Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders, Honolulu, 2001, p. 42

6 Although tuhua was widely traded, just as pounamu from the South Island made its way north, the singular character of its use in this sculpture suggests an origin more local to its source.

7 For a list of most interpretations see Mead, Te Toi Whakairo: The Art of Maori Carving, Auckland, 1986, p. 244

8 Neich in Starzecka, ed., Maori: Art and Culture, London, 1996, p. 86

9 Neich, Carved Histories: Rotorua Ngati Tarawhai Woodcarving, Auckland, 2001, p. 280

10 Ibid., p. 281

11 Neich, Carved Histories: Rotorua Ngati Tarawhai Woodcarving, Auckland, 2001, p. 281

12 Cruise, Journal of a Ten Months' Residence in New Zealand, London, 1823, p. 27

13 Jules Dumont d'Urville, Voyage de la corvette l'Astrolabe […], Paris, 1833, pl. 59

14 Ibid.

15 Brown, Tai Tokerau Whakairo Rakau: Northland Maori Wood Carving, Auckland, 2011, p. 106

16 Neich in Starzecka, ed., Maori: Art and Culture, London, 1996, p. 102

17 Neich in Starzecka, ed., Maori: Art and Culture, London, 1996, p. 76

18 Most of Oldman’s private collection was bought in 1948 by the Government of New Zealand. It is now divided between several museums, with the majority of the Maori material in the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington.

19 As Terence Barrow notes, "The Duff did not call at New Zealand, but 'curios' were often exchanged by sailors, and it is probable Captain Wilson or his men [acquired objects] from another ship at some point of call." Barrow, Maori Wood Sculpture of New Zealand, Auckland, 1974, p. 71

20 de La Beaumelle et al., André Breton. La beauté convulsive

, Paris, 1991, p. 427

21 Cowling, "The Eskimos, the American Indians and the Surrealists", Art

History

, Vol. 1, No. 4, December 1978, p. 487

22 Cited by Cowling,"'L'œil sauvage': Oceanic Art and the Surrealists", in Greub, ed., Art of Northwest New Guinea: from Geelvink Bay, Humboldt Bay, and Lake Sentani, New York, 1992, p. 180

23 Peltier, "From Oceania" in Rubin, ed., "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, New York, 1984, vol. 1, p. 114

24 See Leloup, Statuaire Dogon, Strasbourg, 1994, p. 73, for a discussion of Chadourne's assistance in Rubinstein's purchase of Lem's collection.