Pliny | Historia naturalis, the Macclesfield copy, printed on vellum, Rome: Sweynheym and Pannartz, 1470

Auction Closed

December 9, 09:48 PM GMT

Estimate

900,000 - 1,200,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Plinius Secundus, Gaius (Pliny, the Elder)

Historia naturalis. Ed: Johannes Andreas, bishop of Aleria. Rome: Conradus Sweynheym and Arnoldus Pannartz, [between 8 April and 30 August] 1470

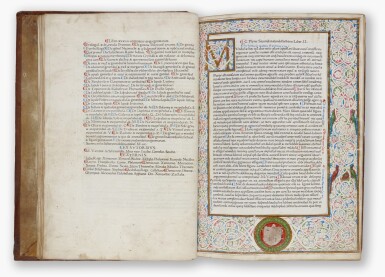

Folio printed on vellum (380 x 270 mm, variable). Roman types, 46 lines (headlines written in black ink as numerals, with occasional words), initial spaces, rubricated throughout in red and blue, marginal headings in blue and red, with chapter numbers added in red, gilt Roman white vine-work initials on red, blue, and green grounds for each book, mostly seven-line (initial for Book VIII eight-lines) with blue and white marginal flourishes, initial for Book II a large M incorporated into the elaborate border decoration, Book XVII with added gilt French seven-line initial N on blue ground, similar French two-line initials in preliminary leaves; a very little light, scattered soiling, abrasion to arms incorporated into the illumination on 3/1r. Late sixteenth-century French blind-stamped calf, covers with central olive-wreath ornament within a frame of blind-ruled fillets, spine in seven compartments, second gilt-lettered with title, others with blind fleurs-de-lys, gilt edges; minor restoration to head and foot of spine and other extremities, some light scuffing.

Collation, Contents, and Manuscript Leaves

110 212 (fos. 1–22): fo 1 blank; dedication; prelims; contents table = liber I

3–610 7–118 (fos. 23–102): libri II–VIII

12–1710 18–208 (fos. 103–186): libri IX–XVII)

21–2710 28–298 3010 (fos. 187–282): libri XVIII-XXVII

31–3710 38–398 4010 (fos. 283–378; without the final two blanks): libri XXVIII–XXXVII

The present Macclesfield copy—one of three of the edition printed on vellum—contains twenty-five leaves in exactly contemporary manuscript: they are gatherings 21–2210, plus leaves 1r–5v of gathering 2310, thus leaves 187–211 of the edition. They are illuminated, rubricated, and annotated uniformly with the printed leaves and, most significantly, in quire 23, fos. 6–10 are printed. Thus, quire 23 is unlike anything known elsewhere: it has five sheets, and the first half of all five were unprinted, while the second half were printed. This is essentially incontrovertible proof that the manuscript leaves were supplied in the Sweynheym and Pannartz shop, and they are rubricated by the same hand that ornamented the printed leaves. The text of the manuscript leaves is almost all of libri XVIII–XIX, which begin on 187r, and XX ends on (printed) 212v = 23/6v.

Second edition, printed in about 300 copies, little more than six months after the first, error-riddled, edition printed by Johannes de Spira in Venice (Goff P786; ISTC ip00786000), but set from an independent and superior manuscript source, edited by Giovanni Andrea Bussi, Bishop of Aleria (1417–1475). Bussi’s edition had been planned before the Venice edition appeared, as he references it in his edition of Aulus Gellius printed by Sweynheym and Pannartz and dated 11 April 1469 (Goff G118; ISTC ig00118000).

(Should it seem ungenerous to describe the first edition as “error-ridden,” Davies wrote, “According to Sabbadini, who sampled Pliny's preface in a number of fifteenth-century redactions, de Spira's edition is without critical ambitions, and what might seem to be editorial interventions turn out to be gross errors of the printers or of their manuscript. The Venice edition had the further drawback that the printer had no Greek type and was therefore obliged to leave blank spaces or render the few words in Greek in nonsensical roman letters, which could only draw attention to the defectiveness of the text. We learn from another book that the Pliny was produced in no more than one hundred copies, and indeed it seems to have had no influence on subsequent editions: no humanist used it as a base text upon which to propose emendations; no one concerned with such matters appears to have owned this particular edition; as a text it was never reprinted” [p. 242]).

The printer’s copy for the second half of the Rome edition, libri XVIII–XXXVII, is in the Vatican (Ms. Vat. lat. 5991); the presumed companion manuscript for the first half has not been found. ISTC notes that “Bussi completed the ‘recognitio’ of the printer's copy of Books 18–37 on 8 April (MS Vat. lat. 5991; see P. Casciano in Scritture, biblioteche e stampa a Roma I, Città del Vaticano, 1980, p. 384) and Franciscus Philelphus enquired about the price on 25 July 1470 (L.A. Sheppard in The Library, ser. IV, 16 [1935], p. 7)." It should be noted that that libri XVIII–XXXVII equal exactly quires 21–40, essentially the second half of the work, the composition of which again is divided in half: fos. 187–282 and 283–378.

As for the superiority of the text of the Rome edition to the just-earlier Venetian, Davies states that Bussi consulted three manuscript, not just one; that he embraced “a range of activities from looking over a piece of work to revision, correction and tidying up—in short, everything involved in what we call editing”; that he reviewed and amended his own work; that he filled in lacunae from other manuscripts he consulted in addition to his principal three; that he usually transliterated the Greek words in the manuscript, “which must have spared the printers some trouble”; that he even did a great deal of copy-editing: adding or correcting punctuation, capitalization, and other accidentals.

“The ‘Natural History’ of Pliny the Elder is more than a natural history: it is an encyclopaedia of all the knowledge of the ancient world. The famous story of Pliny’s death while trying to observe the eruption of Vesuvius at closer quarters than was prudent is often, and justly, cited as an example of the devoted curiosity on which the furthering of knowledge depends. … He was a compiler rather than an original thinker, and the importance of this book depends more on his exhaustive reading (he quotes over four hundred authorities, Greek and Latin) than on his original work. All the spare time allowed him by a busy administrative career was devoted to reading; he began long before daybreak, his nephew the younger Pliny recorded, and grudged every minute not spent in study; no book was so bad, he used to say, as not to contain something of value. When he died the ‘Natural History’ (the sole extant work out of one hundred and two volumes from his pen) was still incomplete. It comprises thirty-seven books dealing with mathematics and physics, geography and astronomy, medicine and zoology, anthropology and physiology, philosophy and history, agriculture and mineralogy, the arts and letters. … The Historia soon became a standard book of reference: abstracts and abridgements appeared by the third century. Bede owned a copy, Alcuin sent the early books to Charlemagne, and Dicuil, the Irish geographer, quotes him in the ninth century. It was the basis of Isidore’s Etymologiae (see lot 7) and such medieval encyclopaedias as the Speculum Majus of Vincent of Beauvais and the Catholicon of Balbus” (Printing and the Mind of Man).

Paul Quarrie, FSA, described this copy of the Sweynheym and Pannartz Pliny as “the grandest printed book in the Macclesfield Library,” which is by consensus considered to be the greatest English family library to be sold in over a century. The Macclesfield copy is one of three printed on vellum, and was presumably printed for a French ecclesiastic, the side notes and headlines being in French hands. (An obvious, if inconclusive, candidate would be Cardinal Guillaume d’Estouteville, who campaigned for the papacy after the death of Paul II in 1471.) Of the two other vellum copies, that at the Bibliothèque nationale de France was the dedication copy to Paul II, while there is no evidence for the early ownership of vellum copy at the John Rylands Library. Even the paper issue is very rare on the market: only two copies are recorded in the auction records since 1962: from the libraries of Giannalisa Feltrinelli (1997) and Joseph A. Freilich (2001).

A spectacular copy of the first authoritative edition of Pliny, a work uniting the “learning of classical and Hellenistic Greece with the old traditions of Rome … [and with] new knowledge brought back from the ends of the world by Roman traders and armies” (Murphy, p. 13).

REFERENCES

BMC IV 9 (IC.17140); Goff P787; GW M34306; ISTC ip00787000; Osler (IM) 4; Printing and the Mind of Man 5; cf. Martin Davies, “Making Sense of Pliny in the Quattrocento,” in Renaissance Studies 9, no. 2 (June 1995):240–257; cf. Trevor Murphy, Pliny the Elder's Natural History: The Empire in the Encyclopedia (Oxford University Press, 2004)

PROVENANCE

A first, almost certainly French owner (scratched and now illegible arms incorporated into the illumination on 3/1r [fo. 23], the beginning of book II, the text proper) — François Grudé Sieur de la Croix du Maine (1552–1592, historian and bibliographer); presented, 1587, to — Nicolas Michel, sieur Després (d. 1597, physician and scholar); bequeathed to — the Sieur de Savigny; presented, 1616, to — the Jesuit College at Caen; presented, 1704, to — Nicolas Joseph Foucault, marquis de Magny (1643–1721; armorial bookplate) [the preceding five provenances recorded in an inscription on the front vellum flyleaf]; acquired, at an unknown time and perhaps during Foucault’s lifetime, by — Thomas Parker, the first Earl of Macclesfield (1667–1732); by descent to — George Parker, the second Earl of Macclesfield (1697–1764); by descent to — Thomas Parker the third Earl of Macclesfield (1723–1795); by descent to — successive Earls of Macclesfield until sold, Sotheby’s London, 25 October 2005, “The Library of the Earls of Macclesfield removed from Shirburn Castle, Part Six: Science P–Z plus Addenda,” lot 1647 (North Library armorial bookplate with press mark 67.I.10)

We are very grateful to Paul Needham for his consultation on this lot.

You May Also Like