True Connoisseurship: the Collection of Ezra and Cecile Zilkha

Milton Avery

Mender

Auction Closed

December 11, 04:21 PM GMT

Estimate

800,000 - 1,200,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

True Connoisseurship: the Collection of Ezra and Cecile Zilkha

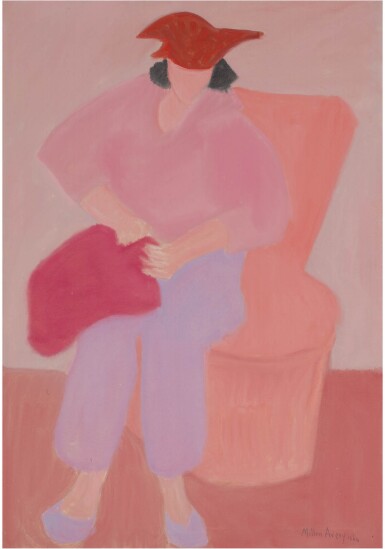

Milton Avery

1885 - 1965

Mender

signed Milton Avery and dated 1960 (lower right); also inscribed "Mender"/by/Milton Avery/40x38/1960 (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

40 by 28 1/4 inches

(101.6 by 71.8 cm)

This lot is accompanied by a letter of authenticity from the Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation, New York.

Acquired by the present owner from the above, 1961

New York, Grace Borgenicht Gallery, Milton Avery: Figure Paintings 1960, January 1961

“I like to seize the one sharp instant in nature, to imprison it by means of ordered shapes and space relationships. To this end I eliminate and simplify, leaving apparently nothing but color and pattern. I am not seeking pure abstraction; rather, the purity and essence of the idea – expressed in its simplest form.” – Milton Avery

Painted in 1960, Mender exemplifies Milton Avery’s mature style, which emerged in the 1950s. While he had long been concerned with reducing figural and landscape elements into simplified forms, Avery pushed this tendency even further during this period, omitting all components and details he found unnecessary. Avery explained this mounting impulse by saying, “I always take something out of my pictures. I strip the design to essentials; the facts do not interest me as much as the essence of nature” (quoted in Chris Ritter, “A Milton Avery Profile," Art Digest, vol. 27, December 1, 1952, p. 28).

Mender most likely depicts Avery’s beloved wife Sally, who, along with their daughter March, served as the artist’s most important subject and muse. Both women served as frequent sources of inspiration for Avery and images of them pervade his prolific oeuvre. In Mender, Avery simplifies Sally’s figure to only the purest lines and volumes of her form, rejecting all extraneous details or embellishments. Here Avery eschews conventional notions of both color and compositional design: the picture plane is largely flat, and each element is delineated as an independent area of color. Rendering his subject through a two-dimensional design, Avery leaves the realm of purely realistic representation to distill the abstract qualities he saw as inherently present in the forms and figures of the world around him. He is not concerned with portraying the physical likeness of his subject but instead aims to capture her very essence.

“I do not use linear perspective,” Avery remarked, “but achieve depth by color—the function of one color with another. I strip the design to the essentials; the facts do not interest me as much as the essence of nature” (as quoted in Robert Hobbs, Milton Avery: The Late Paintings, New York, 2001, p. 51). Through this process of simplification, Avery eliminates facial details entirely. Of this formal reduction, art historian Robert Hobbs observes, “...in his quest for purity of formal means and the essence of expression, facial features became too dominant as focal points and too illustrative, thus interrupting the viewer’s understanding of an entire composition as the embodiment of a mood expressed in terms of the medium of paint” (Milton Avery, New York, 1990, p. 129).

In its reductive palette of tonal color, Mender presages the works of such iconic painters as Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko (Fig. 1) and the proponents of the Color Field movement, who would go on to push his innovative ideas fully into the non-objective. Today, Avery is considered among the earliest American practitioners of chromatic abstraction. In a commemorative essay addressing the impact of Avery’s influential body of work, Rothko concluded, “There have been several others in our generation who have celebrated the world around them, but none with that inevitability where the poetry penetrated every pore of the canvas to the very last touch of the brush. For Avery was a great poet-inventor who had invented sonorities never seen nor heard before. From these we have learned much and will learn more for a long time to come” (as quoted in Adelyn Dohme Breeskin, Milton Avery, Washington, D.C., 1969, n.p.).

You May Also Like