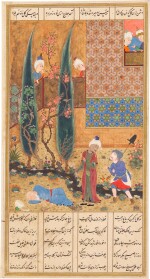

An illustrated leaf from the Makhzan al-Asrar of Nizami: The Disputing Physicians, Persia, Tabriz, Safavid, circa 1525-35

Auction Closed

October 27, 03:41 PM GMT

Estimate

30,000 - 50,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

pen and ink, gouache heightened with gold on paper, 6 lines of text in black nasta'liq script arranged in four columns above and below the painting, gold and black intercolumnar rules, the text panel within narrow gold border, the reverse with 22 lines of text similarly arranged, title in larger gold script in a rectangular text panel against gold foliate scrolls

21.6 by 11.5cm.

This illustrated folio depicts the popular story from Nizami’s Makhzan al-Asrar (part of the Khamsa) in which two competing physicians quarrel over which is superior and agree to settle their differences by way of a duel. The first physician brews a deadly potion and offers it to the second, who drinks it, followed by an antidote of his own making. He survives. The second physician then picks a flower and whispers a spell over it before offering it to the first physician, who is so terrified of the enchantment that he falls down dead.

Here the artist has set the scene in an enclosed garden outside a building. The two physicians are in the foreground, the dead one lying on the ground with his turban adrift, the fatal enchanted flower having fallen from his hand. Beside the physicians is a gardener, while onlookers observe the dramatic scene from a window and behind the garden fence.

The miniature was attributed by S.C. Welch to the royal Safavid artist Mir Musavvir (private communication to the previous owner), and an analysis of the style and compositional elements of the present work generally supports this attribution. Overall the style relates to manuscripts produced at the royal atelier of Shah Tahmasp at Tabriz between 1525 and 1540 when the atelier was at its zenith and producing such outstanding manuscripts as the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh and the Shah Tahmasp Khamsa of Nizami of 1539-43. Detailed comparisons of several elements in the present work reveal close similarities to the style associated with works signed by or attributed to Mir Musavvir in the royal Shahnama manuscript. Compositional structures of similar design are found on ff.60v, 61v, 89v, 698v (see Canby 2011, nos.67, 68 94, 272). The pale palette of pink, terracotta and sandy browns, especially the particular colours used for the architectural decoration, are found on ff.10r, 60v, 61v, 89v, 698v (see Canby 2011, nos.23, 67, 68, 94, 272). The specific patterns used for the architectural decoration, including the mashrabiyya design on the garden fence, the triangular key fret in the background behind the garden fence, the stars with hexagons on the lower part of the building, the triangular knot motifs with internal hexagons on the upper part of the building, and the square plain bricks or paving outside the building, can be found on ff.10r, 28v, 60v, 61v, 89v, 698v (see Canby 2011, nos.23, 35, 67, 68, 94, 272). Finally, the faces of the figures are very similar to those found on ff.10r, 28v, 60v, 61v, 70v, 89v, 109r, 127v, 130r, 655v (see Canby 2011, nos.23, 35, 67, 68, 77, 94, 102, 113, 114, 268). Overall, the closest comparison is with f.60v, which is the miniature that actually bears Mir Musavvir’s signature (Canby 2011, no.67).

In several of the closest comparisons listed above, Mir Musavvir may have been assisted by Qasim ibn Ali, another of the royal artists in Shah Tahmaps’s atelier and one with whom he frequently collaborated. Furthermore, several of the miniatures attributed to Qasim Ali working under Mir Musavvir’s guidance also show similarities to certain features in the present miniature (e.g. Canby 2011, nos.135, 136 139, 140, 145, 154 and 236). Thus it may be that the present miniature was also a product of their collaboration.

The present folio is trimmed to just outside the text area, which measures 21.6 by 11.5cm, meaning that the complete page would probably have measured approximately 30 by 20cm. The style and relatively small scale of the present work point to a date of production around 1525-35, when several other manuscripts of a similar scale and type were produced in Tabriz. These include a small Shahnameh of Firdausi in the National Library of Russia (see Loukonine and Ivanov 2003, no.172, pp.151, 155), a manuscript of the Khalnama of Arifi copied by Shah Tahmasp himself and illustrated by court artists (National Library of Russia, see Loukonine and Ivanov 2003, no.173, pp.156-7), and the well-known Diwan of Hafiz, now dated to 1531-33 (Harvard Art Museums and Metropolitan Museum of Art, see Welch 1979, nos.40-44). These manuscripts were produced under royal patronage, but are on a smaller, more intimate scale than Shah Tahmasp’s great Shahnameh or Khamsa manuscripts. It is probable that the present leaf is from a dispersed manuscript produced in a similar context, possibly from a complete work of Nizami’s Khamsa, or from a single edition of the Makhzan al-Asrar. Apparently, no other folios from this manuscript are currently known.

Mir Musavvir was one of the greatest of early Safavid royal artists and the second director of the royal Shahnameh project. His work was admired equally with that of Sultan Muhammad and Aqa Mirak, and the Safavid artist and biographer Dust Muhammad considered these three artists to be on the same level of excellence. S.C. Welch described him as 'the most intellectual' of the major artists and one whose work was full of balance and harmony (Dickson and Welch 1981, vol.I, pp.87-88). Qadi Ahmad described him as "a portraitist whose work was flawless… who produced paintings of the utmost charm and elegance". He was the father of the painter Mir Sayyid Ali, and when the Mughal emperor Humayun was at the Safavid court in the summer of 1544 he offered Shah Tahmasp a large sum of money to buy Mir Musavvir’s services. The historian Taqi of Isfahan noted that Mir Musavvir "encompassed all the arts, such that decorative painting and illumination were raised to their heights on banners of his lofty fame; and he had a special flair for figural painting, being quick yet meticulous" (Dickson and Welch 1981, vol.I, pp.87-88).

You May Also Like