Image: © Bernd Jansen

Artwork: © Jörg Immendorff 2021

During the 1960s Jörg Immendorff cultivated a name for himself as an artist-agitator. Driven by the potential of social transformation through art, an approach to ‘art-making’ very much influenced by his mentor and professor at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Joseph Beuys, Immendorff channelled the political landscape of late twentieth-century history into works that span performance, protest, and painting. Conceived and exhibited in 1979, Teilbau Bleckede belongs to a seminal body of work focused on the political and emotional division of Germany during the Cold War era. Very much related to the important Café Deutschland series of 1977-1983 – works in which the opposing ideologies of East and West Germany are staged within highly symbolic and theatrical compositions – this painting explores the turbulent politics of its time, a moment in history in which the possibility of a reunified Germany seemed a distant reality.

“Because Germany in the late 1970s still found itself deeply mired in the Cold War, an ice age prevails in these images, one filled with ice floes and fields of snow."

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Image: © 2021The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

Artwork: © Jörg Immendorff 2021

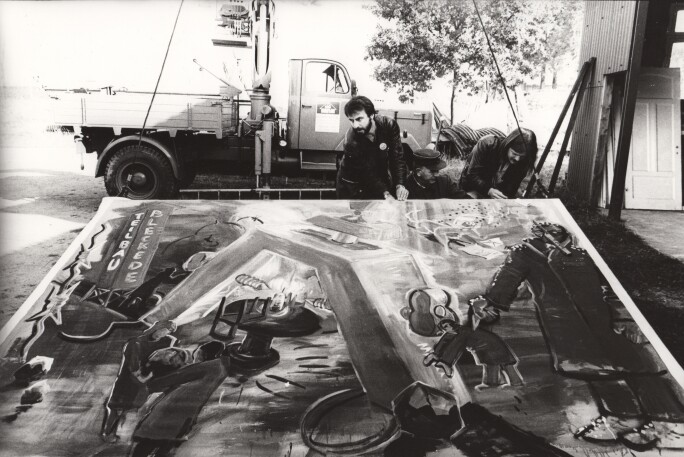

Born into a newly divided country in 1945, Immendorff grew up in Bleckede, a town close to Lüneburg in Lower Saxony. Following the demarcation of Allied and Soviet zones after the Second World War, Bleckede became a divided town. The river Elbe, which demarcated the East-West border, runs through Bleckede and so the town was carved into British and Soviet territories; anyone who lived too close to the inner border between the occupied zones was evacuated and their houses demolished. For those living there, this brutal division would have palpably affected day-to-day life, and, as evinced by the present work, undoubtedly made a lasting emotional impact on the young Immendorff. Teilbau Bleckede was originally created as part of a double-sided painting-installation that was erected on the banks of the river Elbe in October 1979. Mounted with their backs to one another and hoisted up onto a former crane pedestal, part I pointed west and part II pointed east – one faced the FDR and the other faced the GDR. Owing to weather damage, part II is no longer extant, although the captioned wooden plaque that Immendorff mounted to the crane’s base is today preserved in the Bleckede municipal archives. Executed in icy tones of white and grey, and accented with passages of yellow, black and red – the colours of the German flag no less – a number of diminutive figures carry out physical tasks under the domineering presence of a heavy set, perhaps military garbed, figure. The barbed wire and watch-tower structure containing the work’s title underlines the forcefully imposed schism of a country that had literally been torn in two. The snow flurries, burning candle, upturned chair, and the vice-like gate that dominates the centre of the composition are here coded signs and symbols that evoke a country bitterly entrenched in a political ice-age as the Cold War raged on. This painting delivers a thought-provoking response to collective turmoil and a melancholic sense of loss; the important and significant moment of its installation in Immendorff’s hometown offers a powerful statement on the political and psychological schism of a nation coming to terms with its identity following the Second World War. Articulated in a representational style evocative of the East-German endorsed Socialist Realism, Immendorff stages the ideological conflicts of his time in a painterly manner deemed retrograde and suspect by his West German contemporaries and Dusseldorf Academy mentor Joseph Beuys.

Image: © Bernd Jansen

Artwork: © Jörg Immendorff 2021

Having originally studied set design, Immendorff commenced his formal artistic training under Beuys in 1964 at a time when the elder artist was at the very height of his influence and critical success. Under Beuys’s tutelage, Immendorff almost immediately began making ground-breaking works: socially engaged events, objects, and paintings that challenged a traditional fine art practice and were geared towards political change. Deeply affected by the Beuysian notion that art can play a wider role in society, Immendorff, who would later be expelled for Maoist activism, became one of Beuys’s most assiduous acolytes: among many notable alumni he was the only student from whom Beuys ever bought a painting, and he notably served as one of the artist’s assistants during the legendary performance How One Explains Painting to the Dead Hare (1965). The late 1960s thus brought forth several important protest/event-led pieces, including the LIDL works and actions. Fuelled by anti-Vietnam war sentiment and named after the sound of a baby’s rattle, LIDL, to quote Arthur C. Danto, “used regressive conduct as a means of cultural protest” (A. C. Danto, ‘Jörg Immendorff: German Artist’, Artforum, April 2001, online). As the 1960s turned into the 1970s, however, Immendorff was increasingly drawn to a more traditional form of expression – painting.

Image: © Bernd Jansen

Artwork: © Jörg Immendorff 2021

Forming a love-hate dialogue that was in-keeping with his anti-establishment and iconoclastic practice, Immendorff launched a critique of painting that espoused the medium itself. Described by art historian Peter-Klaus Schuster as “anti-pictorial allegory – an instance of programmatic painting against painting”, Immendorff’s early paintings issued paradoxical leftist instruction: those depicted (often artists cooped up in studios working on canvases) are urged to drop sticks, head to the street and take up the political struggle (P. Schuster, ‘A “Raphael without Hands”: On Immendorf’s Perplexing Artistic Strategies’ in: Exh. Cat., Berlin, Neue Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Jörg Immendorff: Male Lago, 2005, p. 52). For Immendorff, painting was a means to educate and enact in the real world, not exist in an aesthetic realm utterly unto itself. With the present work and the series of vital paintings executed during the period of Germany’s divided state, Immendorff sought a form of political-educational agitation, “to live and change consciousness”; as the artist once explained: “This I would call social and political work” (J. Immendorff, B. H. D. Buchloh, trans., HIER UND JETZT: DAS TUN, WAS ZU TUN IST, Cologne and New York 1973, p. 218).