R aúl Martínez created the one of the most defining visual lexicons of Contemporary Art produced in the Americas. His legacy reveals the communicative possibilities of art via its articulation of the new realities of Cuba in the wake of the 1959 Revolution. Among his body of work, 9 repeticiones de Fidel y microfonos, is situated among the most provocative works of the global Pop Art movement.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 brought an abrupt and seismic revision to the political, socio-economic and cultural life of the island, when the guerilla movement led by Fidel Castro succeeded in toppling the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. The artistic production of the 1960s and 1970s that followed serves as a visual, historic documentary of the pervasive influence of the Revolution. The status of the image as a powerful arbiter of messaging became more urgent and prominent as mass consumer culture, global political tensions (i.e. the Cold War and the Vietnam War) and social movements (including the American Civil Rights and global Feminist movements) shaped the iconography of the era. Whether as a tool for state propaganda or to subvert official discourses, “artists and graphic designers in Cuba took hold of visual strategies associated with POP art.” (Jennifer Josten, “Revolutionary Currents: Pop Design Between Cuba, Mexico and California”, in POP AMÉRICA 1965-1975 (exhibition catalogue), Durham, 2019, p. 73).

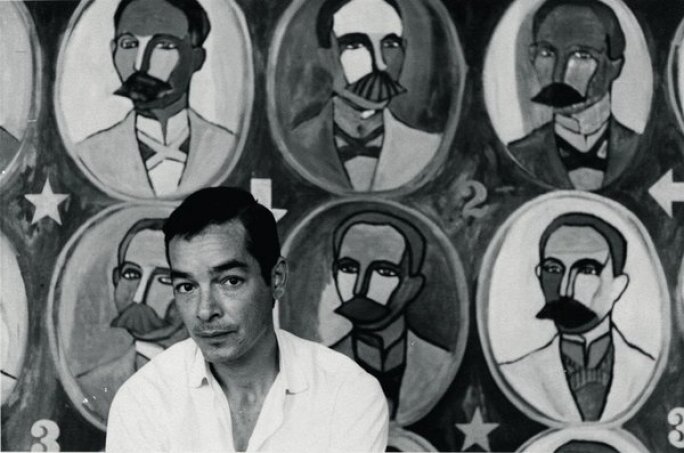

An energetic and ceaseless experimenter, Martínez’s oeuvre includes painting, photography, poster, magazine and billboard design; his productive output is regarded as a catalyst for the rise of Pop art in Cuba. After studying first at Havana’s famed Academia San Alejandro, he later went to Chicago’s Institute of Design in 1952 where he embraced the tenets of founder and former Bauhaus master Lázló Moholy-Nagy. Martínez’s return to Cuba in 1953 marked the rapid evolution of his creative production. While working as a publicist and design director for an advertising agency, Martínez took on his own independent artistic explorations, first with abstraction, then moving towards a more narrative figuration. In the midst of formulating his visual vocabulary, the sweeping nationalization programs of the 1959 Revolution took effect; Martínez immediately began working for the state as a commercial artist.

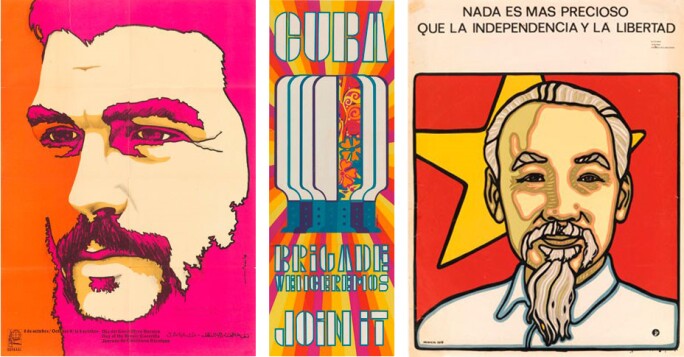

The Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC) and the Organización de Solidaridad con los Pueblos de Asia, África y América Latina (OSPAAL) were among the first cultural organizations created shortly after the victory of the Revolution. Both the ICAIC and OSPAAL were tools used by the new political regime to communicate Fidel Castro’s vision of a socialist society, producing wide-release films and printing hundreds of posters distributed throughout the island. While “Andy Warhol is often credited with popularizing silkscreen (also known as serigraphy) as an artistic medium when Marilyn Monroe’s tragic death in 1962 led to his first serial reproductions,” the technique had in fact “already been pressed into use by 1961” for the ICAIC and OSPAAL posters (ibid, p. 73.) The course of Cuba’s poster movement rapidly shifted towards Pop as a result of these visual design innovations.

Centre: Antonio Fernández Reboiro, Cuba brigate venceremos join it, 1969

Right: René Mederos, Ho Chi Minh, 1969

As art historian and professor Jennifer Josten observes in her recently published analysis of the development of Pop throughout the Americas: “while Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and others adapted the language of mass consumer culture to paintings for the New York art market, artists allied with progressive social movements [such as in Cuba] deployed similar devices – particularly the serially repeated, high contrast photographic image and the heavily outlined cartoon figure – in mass-produced posters that demanded an end to neo-imperialist policies and practices throughout the world [and] to articulate messages of affirmation and international solidarity” (ibid, p. 73.)

The 1959 Revolution would not only have significant impact on the development of Martínez’s unique version of Pop Art, its events would feed the entirety of his imagery from the mid-1960s onwards. Using photography to explore social themes, he began capturing the changing rhythms of daily life provoked by the social reordering of the new political regime. He added words and collaged photographs onto painted surfaces of canvas, akin to his North American peer Robert Rauschenberg. It was then that Martínez realized that the mass-produced, public poster was “revolutionary Cuba’s truest art form” and applied this theory to his easel painting (ibid., p. 73).

Beginning in 1966, Martínez translated the design sensibilities of his commercial practice to portraiture. Employing quintessential elements of Pop Art, he creates a grid-like pattern of serialized images of political figures such as José Martí, Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. Like Andy Warhol, Raúl Martínez used the faces of instantly recognizable cultural icons—in this case political heroes of the international counter-culture movements— immortalizing their mythical status with their endless multiplication across the canvas. Calling these works Landscapes of the Revolution, he “considered them as reflections of the totally changing environment around him” (Corina Matamoros, Raúl Martínez, la gran familia, Havana, 2012, p. 221).

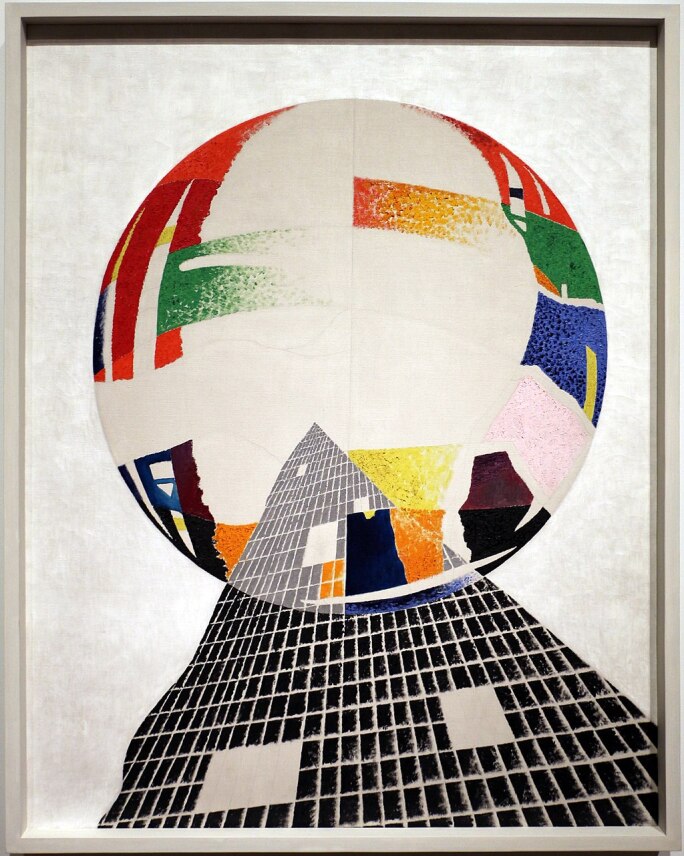

Right: the present work

9 repeticiones de Fidel y micrófonos is emblematic of Martínez’s vision of Pop Art, giving the illusion of political propaganda with its vivid colors and graphic imagery of the populist utopia championed by the Revolution. Dressed in military fatigues, Fidel Castro appears in front of a crowd of microphones, delivering a speech to an unseen audience. A masterful orator, Castro’s speeches were extensively photographed and televised on the island, allowing him to wield extraordinary influence in advancing his socialist message.

The architectonic composition in 9 repeticiones de Fidel y micrófonos is evocative of political posters “where the need for the accurate portrayal of the hero hypnotically dominates the composition” (ibid, p. 222). Making slight “variations to each of his repeated figures by hand” (op. cit., p. 75) (unlike Warhol who applied silkscreen directly to canvas), he invites the viewer on a seemingly impossible quest to identify subtle differences and similarities between the poses, colors, and forms of each of the nine images – perhaps suggesting the variability and, ultimately, fallability of the subject. . . (In these subversive variances Martínez ironically levies control away from the Revolution’s leader. What seems to be as a celebration of Castro and his socialist utopian message is equally an arousal of distrust and a candid, even confrontational, questioning of the new socio-political system.

Works by Raúl Martínez in Important Museum Collections