“Ryman’s [paintings] are the product of the fingers and hand, not the arm. Gesture, for him, served paint rather than the painter; painting was a question of application rather than of ‘action’... What paint had to say was its own name, and it said it best in measured tones.”

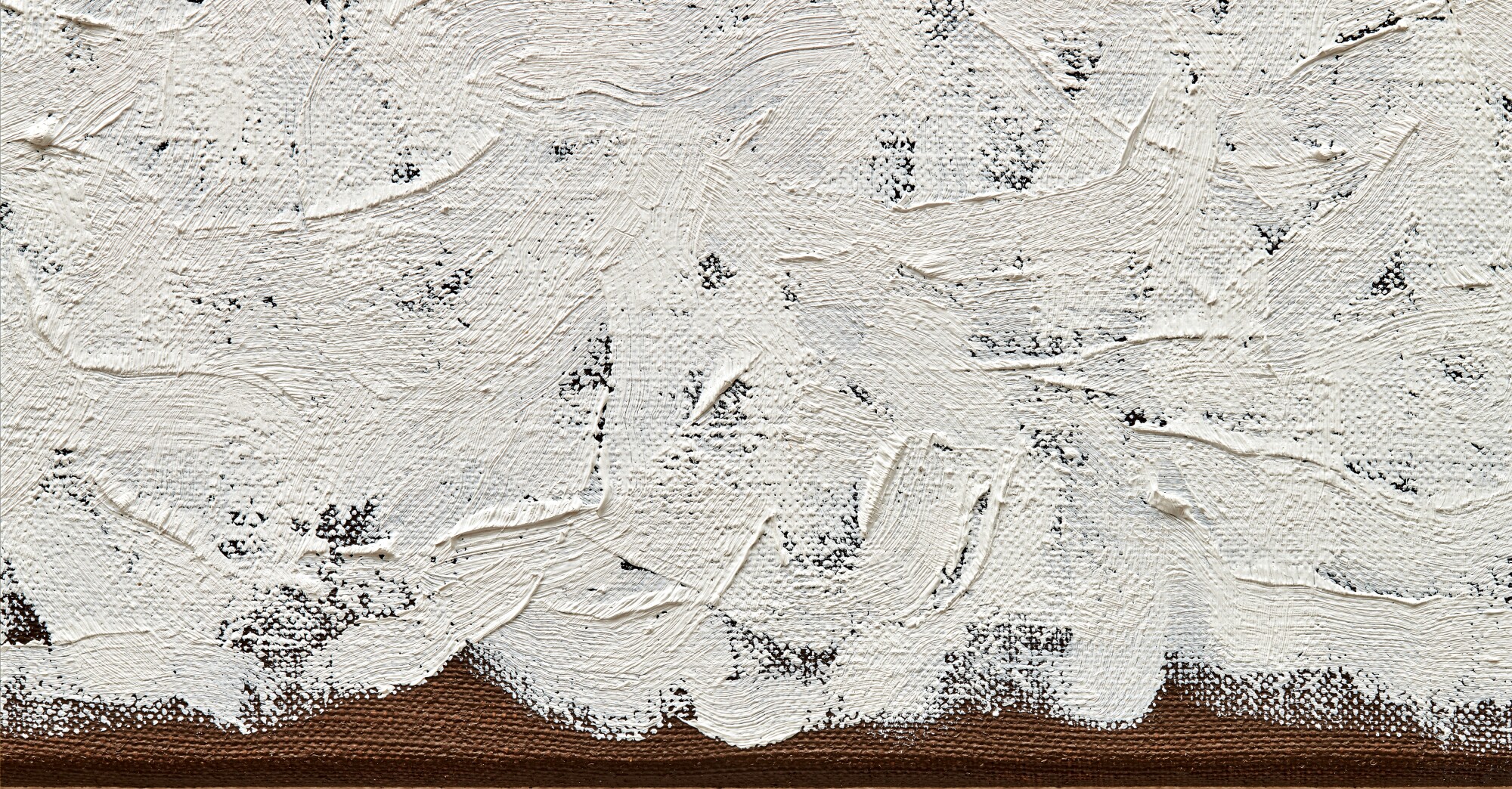

A flurry of painterly bravura, where whorls of delicate impasto peaks give way to smooth serpentine passages of pigment, Branch epitomizes the very best of Robert Ryman’s inimitable oeuvre. An artist of unerring continuity, throughout his career Ryman operated within the self-imposed limitations of a square format and predominantly white pigment, and in doing so undertook an empirical investigation into the essence of painting. Never a question of what to paint, but rather how to paint, Ryman used his square as a starting point to create compositions that reflect the properties of light, redefine the role of the edge, and explore new frontiers of space. At its core, Ryman’s work constitutes an investigation of medium, be that the support or the paint itself, and the resulting work’s interaction with the world around it. Branch epitomizes these concerns; allied to the wall by means of steel fasteners, and shimmering and glittering by the light it catches, it sees the artist make use of the entirety of his painterly arsenal, and incontrovertibly confirms both his painterly genius and his unique contribution to the history of Contemporary Art.

Further distinguished by its emergence from the legendary Crex Collection, where it has remained since its acquisition from Konrad Fischer in the year of execution, Branch represents the very best of Robert Ryman’s inimitable oeuvre.

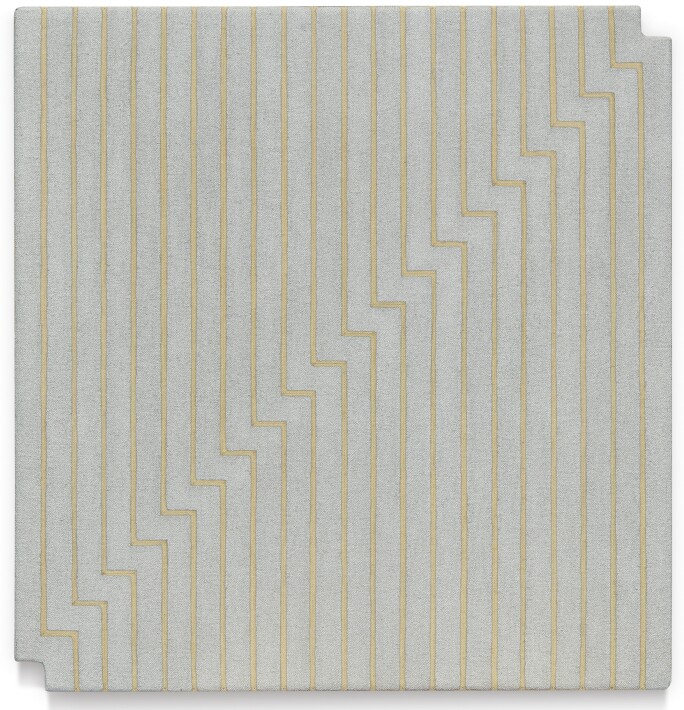

Right: Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1970 The Museum of Modern Art, New York Art © Cy Twombly Foundation

Ryman’s assertion that the content of painting came from the paint itself and not the pictorial outcome revolutionized the characteristically modernist understanding of painting for painting’s sake. Following the fertile period of artistic development in New York after the Second World War, the predominant mode of painting that emerged was one that broke entirely with European traditions—gigantically scaled, gesturally uninhibited, and chromatically varied, this method of expressionism was one which brought the optical properties of color to the fore. Ryman broke free of this influence, finding in the enclosed square format ideal retreat from concerns of proportionality, and with his use white pigment an emphasis on light and materiality, rather than color. While the surface of Branch proposes a similar additive gestural syntax to the oil-encrusted abstraction of Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and other of Ryman’s Abstract Expressionist influences, Ryman’s work completely eschews the notion of action painting. As explained by Robert Storr, “Ryman’s are the product of the fingers and hand, not the arm. Gesture, for him, served paint rather than the painter; painting was a question of application rather than of ‘action.’ Contrary, then, to Harold Rosenberg’s view of abstraction as an exercise in the rhetoric of self-affirmation, Ryman understood it even at that formative state as a problem of material syntax. What paint had to say was its own name, and it said it best in measured tones.” (Robert Storr, Exh. Cat., London, Tate Gallery (and travelling), Robert Ryman, 1993, p. 15)

Market Precedent

All Art © 2020 Robert Ryman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The color white has the physical properties that enabled Ryman the most freedom to experiment within the perfect formal arena of the square. The characteristics of white paint that were alluring to Ryman are innumerable: its tone, transparency, vibrancy, richness, and cohesion all provoked grand inspiration for the artist. While Ryman is compared often to Kasimir Malevich or Josef Albers in his utilization of the monochromatic square, his painterly concerns align more closely to with those of Jasper Johns—repelling associations with conceptual art, his pictures rather are embroiled in the corporeal properties of the paint instead of the theoretical capitulations of such influential modernists. Ryman’s paintings do not stand in service to an idea—they stand in service to the surface.

Private Collection. Sold Sotheby’s New York, May 2019 for $4.1 million

For Ryman, the circumstances under which the picture is experienced are as essential as the elements that compose it. In the present work, the steel fasteners that attach the work to the wall emphasize its sculptural quality. By lifting the painting off the wall, an inch into the room, the fasteners serve, in Ryman’s words, to bring the "wall plane into the painting. When the painting is removed from the wall it loses its composition and ceases to exist. Without the fasteners it is not complete." (the artist in conversation with Robert Storr in: Exh. Cat., Vienna. Galerie Nächt St. Stephen, Abstract Painting of America and Europe, 1988, p. 219) Ryman's treatment of edges has a similar function. The exposure of the support and the absence of paint on one or more edges, as in Branch, serve to unify the whole by emphasizing its construction. As Christel Sauer noted in 1991, “Considerations regarding the size and depth of the painting, that is, the effects of the painting in space are closely related to decisions concerning materials and their reaction on the incidence of light. Very early on, Ryman concerned himself with the question of where the borders of the painting are and how its transition to the wall and the room is constituted.'' (Exh. Cat., Paris, Espace d'Art Contemporain (and travelling), Ryman, 1991, p. 25)

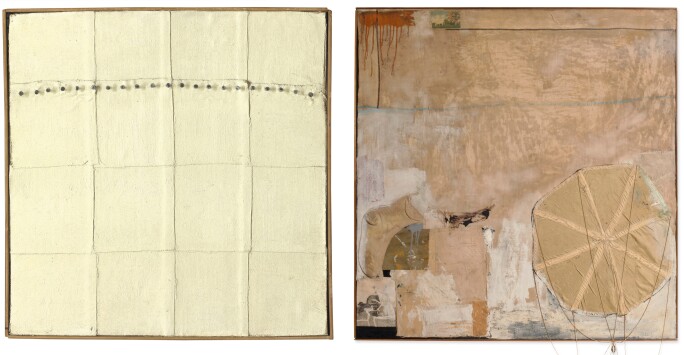

Right: Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled, c. 1955. The Art Institute of Chicago Art © 2020 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Branch sits at the apex of Ryman’s extraordinary oeuvre. Bristling, shimmering impasto peaks give way to smooth, chalky troughs of pigment, and throughout, the brown pigment that Ryman used to prime the canvas lends warmth to the painting, subtly showing through between the infinite cross-hatchings of white. The hanging fixtures activate not only the protruding surface but the room around it, and together the pigment, surface and hanging apparatus constitute not only an investigation into the nature of the painterly medium, but a pioneering exploration of the very limits of painting as a genre. With successive strokes of white serving as overlapping crescendos, Branch incorporates all the defining elements of Ryman’s artistic theory, resulting in a painting that is truly breathtaking to behold.