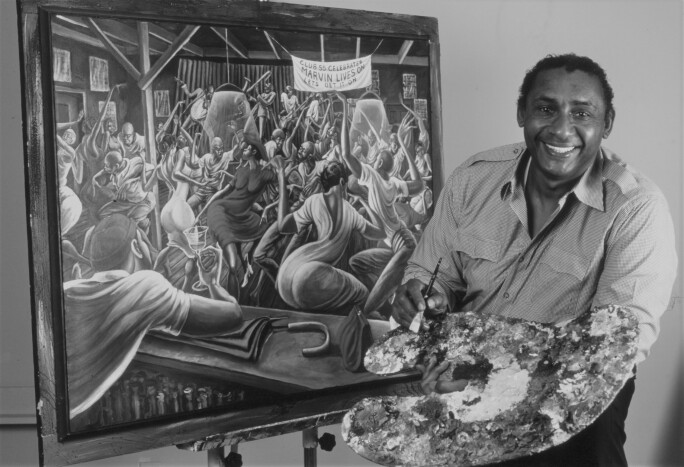

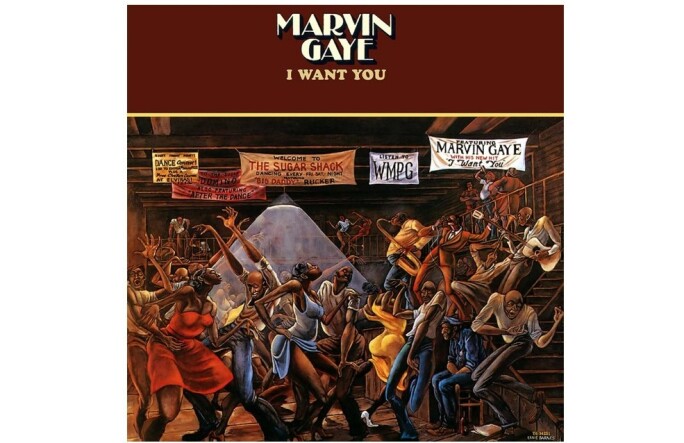

V ibrating with soulful vigor and an inimitable dynamism, Ernie Barnes’ Club 55 is a striking presentation of Black joy which pays homage to music legend Marvin Gaye. Featuring a banner commemorating Gaye’s revolutionary 1973 album Let’s Get It On, the present work epitomizes Barnes’s celebrated legacy for capturing some of the most vivacious depictions of twentieth-century Black life. Displayed in the foreground wearing his iconic red beanie, Gaye raises a glass to dancing crowds and a spirited jazz band rendered in Barnes’ quintessential neo-Mannerist, elongated style of figuration. Begun in 1990 and completed in 1994, the present work was commissioned by Motown Records to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of Gaye's death. The work was later acquired by Motown Records chairman Jheryl Busby. Black musical heritage embodies a central motif across Barnes' celebrated body of work, and the subject matter and provenance of Club 55 is thus testament to his deep reverence for music. Referencing Highway 55 that runs through Barnes's hometown of Durham, North Carolina, and alluding to important early works such as The Sugar Shack and the cover art Barnes created for Gaye's 1976 album I Want You, Club 55 pulsates with the energy and spirit of one of the greatest American painters of the post-war period.

“My work reflects the social contradictions inherent in the myth of deprived peoples... This is the spiritual currency of the ghetto: taking the worst of times and turning them into the best.”

Barnes’ fascination with depicting the purity of bodies in motion began after witnessing a dance at the Durham Armory as a child. Having snuck into the venue, Barnes was immediately enthralled by the sounds and sights of the steamy hall: individuals overwhelmingly carefree with limbs passionately reaching out in every direction to a reverberating beat. This spirit is ever present in Club 55. Overhead lights illuminate a dance floor packed with elongated, sinuous figures as a jazz band passionately plays above them. The music is reflected in the very color of the composition itself, each element more vivid than the next. From Gaye’s bright red beanie to a dancer's electric yellow dress, Barnes translates a moment in time with pure mastery of color and form. Club 55 is housed in its original artist’s frame made of distressed wood, which honors his father and is reminiscent of the picket fence that lined the family's home in Durham.

“There is a great humanity in Barnes’ vision. The more obvious interpretation is that he is intent upon portraying the deep significance of mankind. But on a subtle level he is a purveyor of what Joseph Campbell calls “bliss,” that rapturous state of being attainable by those who commit their intelligence and their imagination to an ideal.”

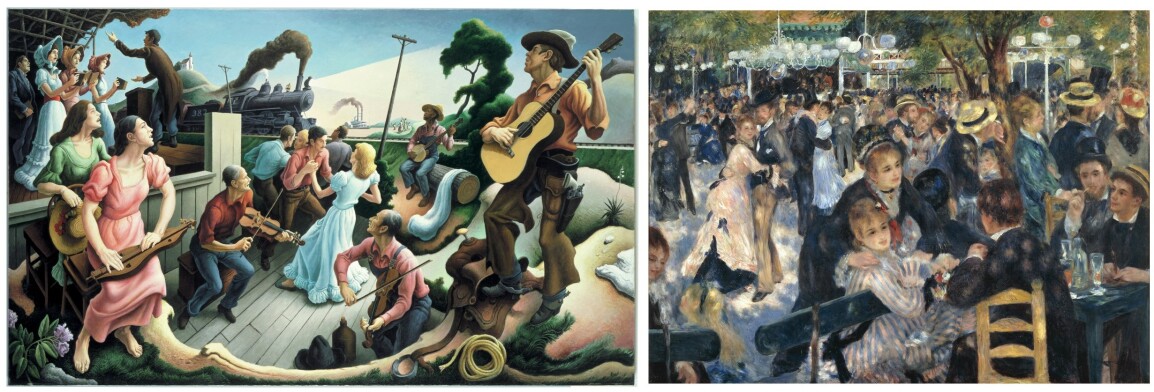

Barnes debuted Club 55 in the acclaimed 1990 exhibition The Beauty of the Ghetto in New York. In response to the Black Is Beautiful cultural movement, the show proposed that “beauty and art are not confined to museums or aristocratic marble halls. Rather… art, life and vitality are bred of struggle and utilized potential, not geography” (Joan D’Arcy, “The Artist,” in Exh. Cat., New York, Grand Central Art Galleries, The Beauty of the Ghetto: An Exhibition of Neo-Mannerist Paintings by Ernie Barnes, October - November 1990, p. 8). Raised in the American South during the Jim Crow era, Barnes was legally banned from entering museums as a child, and instead developed a self-taught knowledge of art history through books and catalogues. By 1965, after a six-year stint as a professional football player in the NFL, Barnes committed to his career as an artist, developing a distinct style that combined the dramatic palette and figuration of European Mannerists like El Greco and Tintoretto with the vibrant genre scenes of American artists such as Charles White and Thomas Hart Benton.

Resplendent with rich colors and boldly expressionistic, Club 55 sees Ernie Barnes extend the aesthetic and narrative tradition of American Realism to convey a resounding portrait of Black musicality. The present work is further elevated with a tactile sculptural quality, with its border of weathered wooden planks that brings life to the floorboards rendered within, transporting the viewer into the rustic interiority of the animated dance hall. The dancers in Club 55 keep their eyes closed, a feature that also functions as a consistent stylistic decision in Barnes’s portraiture to express his negotiation of the racism he has observed first-hand: “I tend to paint everyone, most everyone, with their eyes closed because I feel that we are blind to one another’s humanity, so if we could see the gifts, strengths, and potentials within every human being, then our eyes would open” (The artist quoted in a television interview with Ed Gordon, Personal Diaries, BET, 1990). Barnes’s exuberant depiction of Black life, where figures twist and intertwine, celebrates the sensation of Motown music and the very essence of the artist’s lifelong goal: To affirm the beauty of Blackness through an inescapable, brilliant energy.