Executed in 1891, Gardeuse d’oies is one of the finest examples of Pissarro’s mature œuvre from the period when the artist began emerging from his brief but consequential involvement with the Neo-Impressionist movement. A tranquil scene depicting a young goose girl resting under a tree in a sun-filled meadow, the present work exemplifies Pissarro’s gradual shift away from the strictures of Neo-Impressionism to embrace, once again, a more spontaneous and liberated approach to painting. At the same time, with Gardeuse d’oies Pissarro continued to explore one of the subjects central to his artistic career, that of peasants depicted in their everyday surroundings.

In 1884 Pissarro moved to the village of Éragny-sur-Epte and the rich surrounding countryside would prove a source of inspiration for much of the rest of his career. Pissarro’s first years at Éragny coincided with him adopting a number of Neo-Impressionist techniques in his paintings, with the artist driven by a desire to propel his work forward and away from classic Impressionism, which in his view had by then outgrown itself.

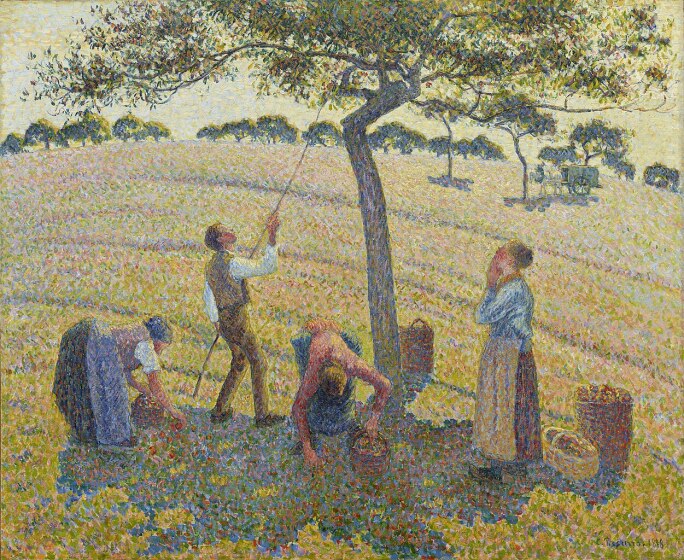

A younger generation of artists, which included Paul Signac and Georges Seurat – whom Pissarro first met in 1885 – sought to reinterpret perception as a “physiological and psychological process that took place between the picture and the viewer” (Christoph Becker in Exh. Cat., Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Camille Pissarro, 1999, p. 102) (fig. 1). They began painting “using spots of unmixed colours, which were dotted individually over the almost white ground, creating the impression of a shimmering pictorial surface” (ibid.). This scientific approach to the application of colour placed the emphasis on the act of viewing. Having embraced this groundbreaking method of working Pissarro produced some of his most striking and innovative canvases (figs. 2-4).

Right: Fig. 3, Camille Pissarro, Les Glaneuses, 1889, oil on canvas, Kunstmuseum Basel

Yet, Pissarro’s embrace of Neo-Impressionism was never doctrinal, particularly when it came to its most “extreme” form, Pointillism, and already in 1888 he wrote to his son Lucien: “How does one obtain the qualities of purity and simplicity of the dot, with the fullness, suppleness, liberty, spontaneity and freshness of sensation of our impressionist art? […] The dot is meager, lacking in body, diaphanous, more monotonous than simple, even in the Seurats, particularly in the Seurats…” (artist quoted in Exh. Cat., Sidney, Art Gallery of New South Wales and Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, Camille Pissarro, 2005, p. 149).

From 1890 onwards, Pissarro’s work started shifting away from Neo-Impressionism (fig. 5). As Joachim Pissarro notes, “The death of Seurat in March 1891 signified the end of Pointillism for Pissarro. At this juncture a number of things changed in his art. He again started using a wet-on-wet technique (as opposed to the Neo-Impressionist method of waiting until each color dried before applying another). This new decision to allow freshly applied colors to interact on the surface offered Pissarro more freedom and room for improvisation. A renewed flexibility and a greater sense of rhythm and movement infused his art during the last decade of his life. This became immediately visible in the figure paintings that he evolved throughout the 1890s” (J. Pissarro in Exh. Cat., Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Innovator, 1994, p. 172).

Gardeuse d’oies is an outstanding example of this subtle shift in Pissarro’s technique. While continuing to embrace a vibrant palette of yellows, greens, blues and pinks he adopted during his Neo-Impressionist years, Pissarro’s brushstroke application here is visibly freer, more spontaneous, resulting in a composition that exudes a sense of movement and masterfully evokes a sensation of a breezy summer’s day with the dappled light dancing across the meadow.

The present work is also a superb rendition of the theme that preoccupied Pissarro for the large part of his career, and which distinguished him from the other Impressionist painters – that of the peasant women and men depicted in their everyday surroundings. While offering a similarly pastoral interpretation of the theme to that of the Impressionists’ predecessors, artists of the Barbizon school (fig. 6), Pissarro’s treatment of this subject had a different angle, focused on expressing a profound respect for these people’s work and the recognition of their life as filled with purpose, dignity and beauty.

As Richard Bretell notes in regard to this, “Rather than peasants, they are more accurately rural workers whose labor in the fields is balanced both by plentiful leisure time and by their participation in the small-scale capitalist economy of French agricultural markets. We never see gleaners taking the dregs of the harvest after the master has housed the grain, nor do we see bodies broken down by work. Instead, they are strong and hardy rather than graceful and conventionally beautiful. Pissarro was perhaps the first great painter of French rural life who actually revealed a kind of relaxed beauty in fieldwork, which he associated with women as much as with men” (R. Bretell in Exh. Cat., Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and Williamstown, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Pissarro’s People, 2011-12, p. 171).

The painting’s first owner was the French author and polemicist Octave Mirbeau, whose crucial cultural legacy lies in his incessant support of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists, including Monet, Gauguin and Pissarro (fig. 7). Upon receiving the present work as a gift from the artist in October 1891, Mirbeau sent him a letter which with a wonderfully poetic sensibility evoked the effect Gardeuse d’oies had on him:

“My very dear friend, the crate arrived only today, in perfect condition. How can I thank you? Upon my word, I wouldn’t know how, my dear Pissarro. What I do know is that I will come round to embrace you. The painting is admirable. It is of course one of the most perfect you have ever done. It caught my eye the other day at your place, and stuck in my mind. That torrent of geese in the shadows steeped with atmosphere, the tranquility of that undulating landscape, the noble outlines of those trees, the crouching girl bathed in air, and the background, that patch of sky between the trees. So distant, so pure, this is of course one of the most stunning conquests of art over nature. The soul of nature is in all this, quivering and so loftily musical... What a poet you are, my dear Pissarro, and what a hard worker! […] What breathes from your canvases is universal life, planetary life; in their reality there is always a splendid reaching out towards infinity. My wife is enthralled with your canvas. She said to me, ‘All the same, it's a jolly lot more painterly than Monet, and more intellectually profound to boot. There’s often an old trace of Romanticism in Monet. Pissarro is absolute perfection.’ And I agreed”

One of the finest paintings by Pissarro from his mature period to come to the market in the recent years, Gardeuse d’oies will be presented at public auction for the first time since 1932, having formed part of the same distinguished private American collection for the past twenty-five years. In the late 1950s, the painting belonged to Sir Simon Marks, 1st Baron Marks of Broughton, one of the founders of Marks and Spencer.