When I was a child, I often dreamed of strange people that were geometric forms… I was fascinated by colour and in my dreams these personages were very colourful.

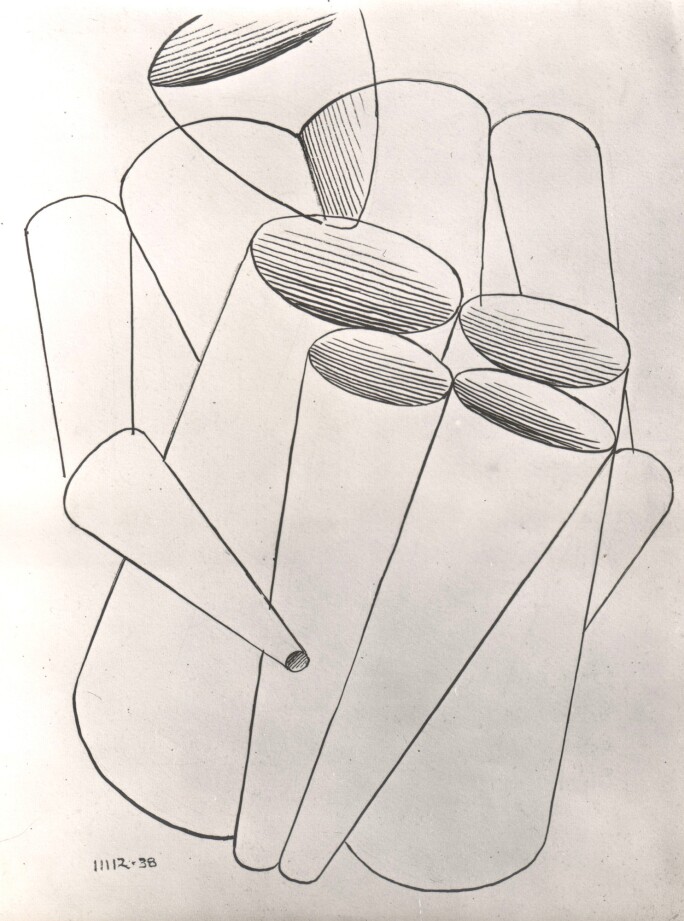

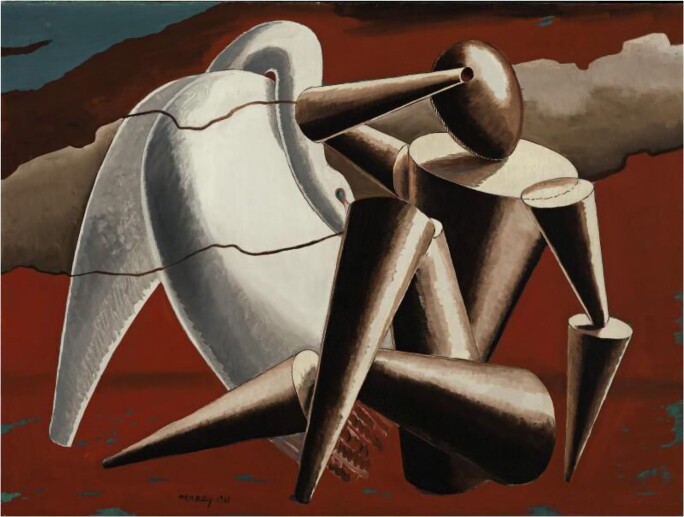

Intriguing and enigmatic, Personnage is a remarkable culmination of Man Ray’s Surrealist paintings of the late 1930s. By 1939, when Personnage was painted after an ink study of 1938, Man Ray had already begun to paint again after abruptly ending a successful career in 1937 as the leading society and fashion photographer. His decision is evident in a letter to his sister, where he writes, “For the past year I’ve been dropping photography and going seriously back to painting” (January 10, 1939, letter to Elsie Ray Siegler), and in 1937 he published La Photographie n’est pas l’art, a portfolio of twelve photographic images that displayed the diversity of Man Ray’s innovative and experimental photography. He sought to distance himself from this highly profitable but creatively limiting activity and devote himself to his true passion as a painter.

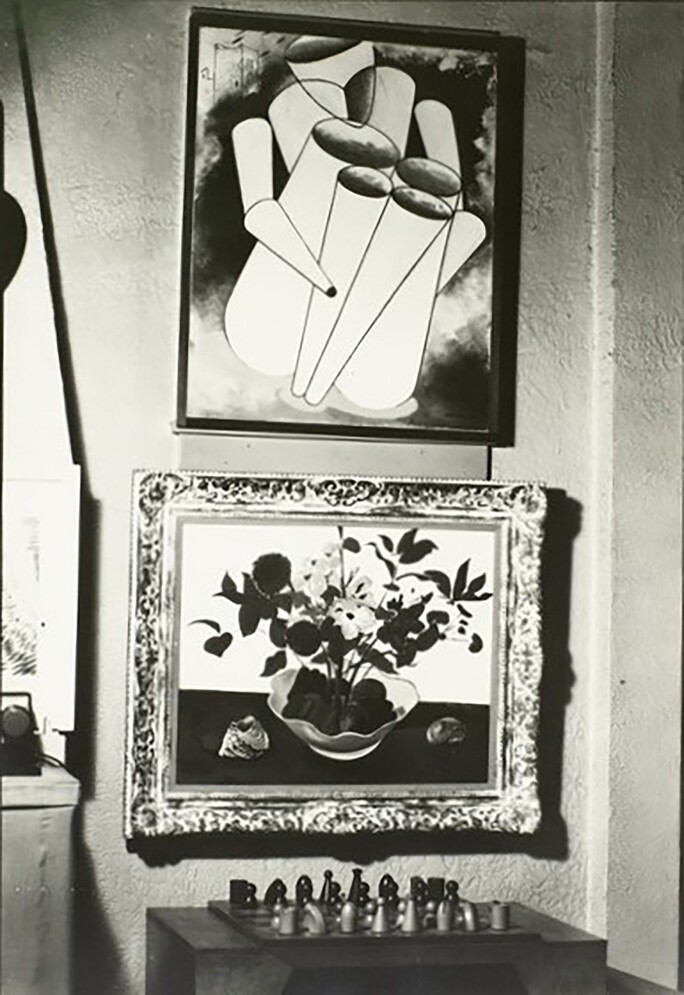

Personnage, a compelling result of the artist’s renewed focus, represents his lifelong interest in geometry. The crouching figure, composed of conic and cylindrical forms, arranged to create an anatomical entity, appears to cast its own blue shadow, which can be interpreted as the mathematical symbol for infinity. These mannequin-like figures, reminiscent of De Chirico’s earlier Metaphysical figures, appear in other paintings and drawings by Man Ray during this period, such as Le Beau Temps (1939), Antipolis (1939) and Acrobat (1940-45). In these paintings the limbs, the upper abdomen and the head are condensed to simplified geometrical forms, with straight and curved lines, representing figures without any clear indication as to their gender. In Le Beau Temps, Man Ray depicts both figures using geometry in its various forms. In La Jumelle (1939), Man Ray creates a human with conic geometrical legs. Later in 1941, once settled in Hollywood, Man Ray uses a similar geometrical figure to create the mythological composition Leda and the Swan, in a setting bathed in blood, a reference to the ongoing war.

Such transformations from geometry to living beings, and vice versa, are prime examples of Man Ray’s exploration and investigation of dehumanisation or objectification. In all these images, Man Ray dehumanises and objectifies man and creates the geometrical human.

Man Ray’s fascination with dehumanisation and objectification began some years earlier: in his 1926 film Emak Bakia, he experimented for the first time with abstract geometrical objects in movement, following his first chess set of 1920, where some of the chess pieces were represented by geometrical objects. In 1926, he created a photographic composition of a mannequin figure resting with simple geometrical forms. Such mannequin figures were to appear in his compositions throughout his career. In 1935, he made a series of photographs of 19th century mathematical objects at the Institut Henri Poincaré in Paris, used to teach algebraic formulae to mathematical students. These highly successful and intriguing photographs were published and exhibited and became the subject of an in-depth article written by André Breton and Christian Zervos, titled “Crise de l’Objet”, published in Cahiers d’Art 1-2 in 1936.

In Personnage, as in the preceding works, seemingly inanimate structures acquire organic vitality and human qualities as a result of Man Ray’s vision and imagination. While the main figure is a geometrical abstraction, the background displays a castle tower in ruins, adding a mysterious dimension to the composition. The tower is part of the Château Lacoste, which Man Ray visited and photographed in 1936. That castle was once home to the Marquis de Sade, whose audacious writings deeply inspired Man Ray and the Surrealists which in consequence resulted in the incorporation of sexuality into Surrealism of the 1930s.

The personage’s self-protecting posture seated and isolated in a barren, fiery landscape, might also reflect Man Ray’s growing fear of the imminent war, and indeed the red dot that replaces the figure’s right hand could have been deliberately painted in that colour implying the impending bloodshed of war.

Personnage brings together many of Man Ray’s innovative disciplines and experimentations combining Sade with dehumanization, objectification and transformation by way of science and geometry, thus making the present painting one of Man Ray’s greatest Surrealist achievements.

Andrew Strauss

MAN RAY EXPERTISE COMMITTEE