"I first used a palette knife, then a piece of wood, then my bare hands, and then my bare feet. In order to place a massive amount of paint on canvas all at once, I had to remove the canvas from the wood frame and affix it directly to the floor. Should I have used a conventional upright canvas placed on an easel, the mass of paint would have created something like a flood-induced landslide or an avalanche on winter mountains. In order to prevent myself from slipping on the paint, I needed to have a piece of rope from the ceiling so that I could hold onto it. Thus began my foot painting, or painting with feet by sliding over canvas."

A

s one of the finest works by the artist to come to auction, Kaien’s (1999) mesmerising dynamism and vigour is as striking as Kazuo Shiraga's most acclaimed early works. Shiraga’s tendency towards minimalistic colour in the early part of his career makes the present work a uniquely superlative piece for its resplendent use of azure and deep black punctuated by moments of fierce red. Created 40 years after the artist first swung across a canvas to kick and heave paint with his feet, Kaien remains as striking and powerful in its dynamic gesture as the artist’s earliest examples of abstract expression. Despite the thrilling visual tension of the contrasting colours that are seemingly enthralled in a visceral struggle, Shiraga’s wide, loose strokes hold a natural elegance, reminiscent of the classical Japanese tradition of calligraphy. Significantly, the present work was exhibited at some of Shiraga’s most acclaimed exhibitions at the turn of the millennium, including the Hyogo Prefecture Museum of Modern Art, Kobe, Annely Juda Fine Art, London and Tokyo Gallery.

Exhibiting a charged, exuberant and exhilarating colour palette, Kaien, the Japanese for 'the depths of the ocean’, recalls the fathomless depth of the sea in its mysterious evocation of the forces of nature. Touches of white at the peripheries of the expansive nearly two-metre piece, like seafoam across a tempestuous sea, are quickly overtaken by transparent shades of blue and powerful strokes of inky black that consume the centre. Buried within this mass of electrifying colour lie delicate interjections of red and violet that create moments of spatial depth and tension within the canvas, as well as drawing attention to the consummate skill and dexterity behind the artist’s acclaimed ‘foot painting’.

白髮一雄在工作室,1963年所攝

Born in 1924 in Amagasaki, Hyogo Prefecture to the family of a kimono business owner, Shiraga was exposed to traditional Japanese art from a young age: calligraphy and antiques, classical theatre and cinema, ukiyo-e prints and ancient Chinese literature. After studying traditional Japanese painting in Kyoto, Shiraga began to move away from the figurative style and pursue a more emotional direction of art, which, in the early 1950s, was marked by a desire to challenge artistic forms. Shiraga’s artistic legacy is rooted in this aspirational post-war period, with Shiraga becoming a renowned representative of Gutai, one of the most highly acclaimed of the new art movements of the time. Informed by the memory of wartime violence, Gutai aimed at the creation of innovative art.

It was in 1954 that Shiraga turned away from the conventional practice of painting with a brush, instead, fastening himself to a rope and using his feet to spread thick visceral layers of paint across his canvas surfaces in vital, gestural movements. Such uninhibited actions allowed the artist to immerse himself within his canvas as opposed to merely pouring or painting from above; by merging body with matter in a cathartic synthesis, Shiraga set himself apart from the gesturality of Western Abstract Expressionism and thrashed out an impassioned path of primal expression. Like no other artist before him, Shiraga’s performative abstractions were vehemently inspirited with movement—“not just the movement of his body […] but also the assertion of matter itself” (Ming Tiampo, ‘Not just beauty, but something horrible’, in Lévy Gorvy, Ed., Body and Matter: The Art of Kazuo Shiraga and Satoru Hoshino, New York 2015, pp. 21-22).

Sold by Sotheby's New York, November 2018 for US$1.9 million

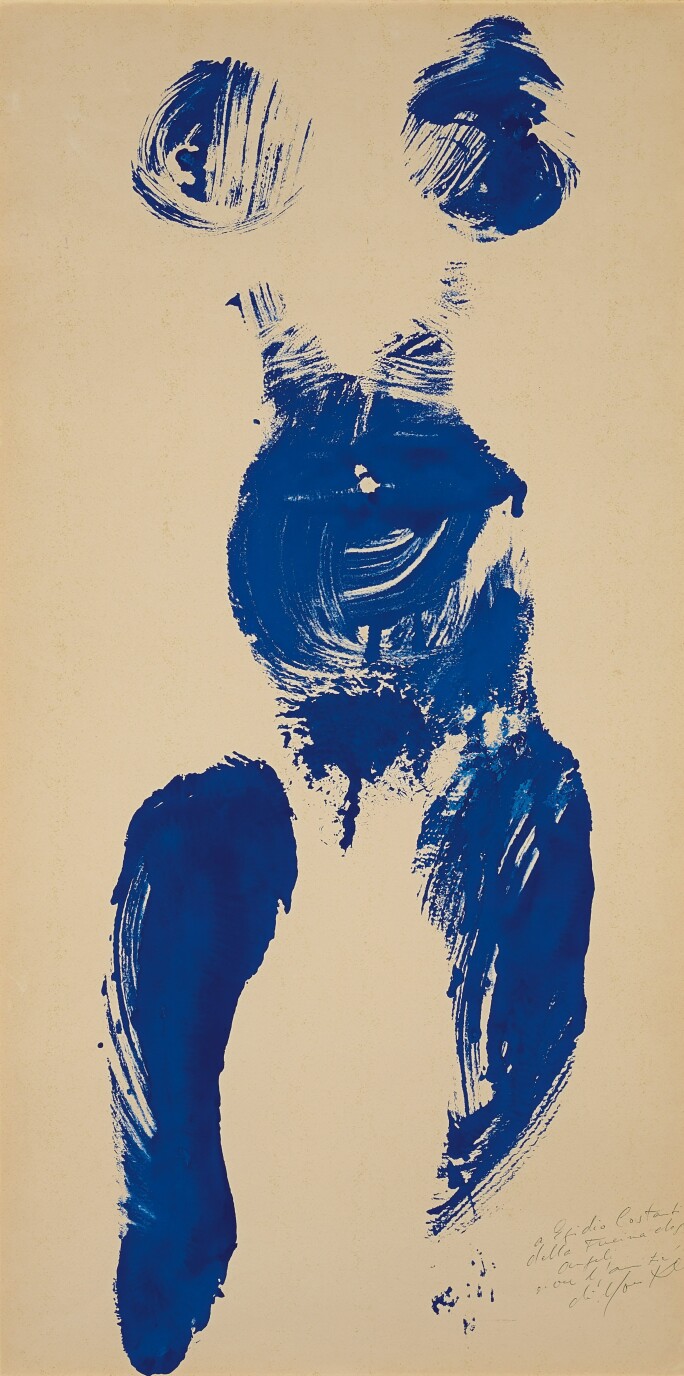

伊夫・克萊因,《無題人體測量學(ANT 163)》,1960年作

2018年11月在紐約蘇富比以190萬美元成交

While Shiraga's drastic act of discarding the paintbrush in favour of the human body aligned him with celebrated Western artists such as Yves Klein, who utilised naked women as ‘human paintbrushes’ in his Anthropometries of 1961, Shiraga’s art utilised his irreducible corporeality to battle with and awaken the raw vitality of matter itself. Such a paradigm epitomised the mission of the post-war Gutai artists who, literally uniting ‘instrument’ (gu) with ‘body’ (tai), rose fearlessly from the rubble of post-Hiroshima Japan to advocate a reinvigorating philosophy of ‘concreteness’ in their war-torn country. Shiraga once said that his art “needs not just beauty, but something horrible” (Kazuo Shiraga, interview with Ming Tiampo, Ashiya, Japan, 1998); by engaging with, and transcending, violence, Shiraga was able to “wrestl[e] with the demons that haunted him and his generation, at the same time opening the possibility of hope for the years ahead” (Exh. Cat., New York, Lévy Gorvy, Body and Matter: The Art of Kazuo Shiraga and Satoru Hoshino, 2015, p. 23).

In Shiraga’s creative process, the artist's feet, body, and mind all become vehicles of the artist's intuition, spontaneity, and emotions. These powerful forces rage against the limits of the painting’s frame in the present work, with the oil pigment and the artist’s technique coming together to rein in the instinctive wildness of these forces which threaten to break free. Shirga’s deft handling of pigment and freeing up of the subconscious guides the abstract shapes on the canvas to create the cyclical dynamics of motion, enticing the viewers' gaze. These opposing forces, together give this work its writhing energy and its profundity. Two broad, powerful lines in black stand vertically to form the geometric framework of the composition, reflecting a choice by Shiraga about the arrangement of the pictorial elements. Yet, these two core lines bend and turn, with traces of other layered colours emerging from the deeper recesses of pigment buried beneath the surface; these finer variations in detail result from the artist using his feet as his paintbrush. This innate sense of structure is derived from Shiraga’s mature control over composition as guided by a complex understanding of form and execution accrued over forty years of artistic excellence.

In his post-Gutai years, Shiraga not only received training in Buddhism but also re-engaged with traditional ink and brush calligraphy to complement his technique and breadth of style. Such a re-embracing of his Eastern roots lends Shiraga’s feet-strokes the essence and soul of masterful ink brushwork, gracing his by-then universally acclaimed canvases with transcendent traces of his Eastern origins. This is evident in his post-Gutai works such as Kaien in which a certain elegant lyricism arises from the loose natural strokes, recalling the classical Japanese tradition of calligraphy and the thrashing physicality of the sea.

一開始我用調色刀繪畫,然后轉用木塊,再是赤手,最後直接赤腳作畫。爲了能在畫布上一次性塗上大量顔料,我要先將畫布從木框架取下,再平鋪在地板上。若我用傳統方法,將畫布垂直於畫架上作畫,顔料就會如洪水引致的山泥傾瀉,或冬日雪山的雪崩般坍塌下來。以防在顔料上滑倒,我從天花板垂挂一條繩索,讓自己抓緊,盪於空中。就是這樣,我發明了足繪,開始以足蘸顔料,在畫布上滑行作畫。

《海

炎》(1999年作)堪稱白髮一雄迄今上拍畫作中極為精美的作品之一。畫作洋溢的迷人動感魄力,與藝術家廣受讚譽的早期作品一樣令人驚艷。白髮一雄早期傾向以極簡的顔色作畫,與之相比,本作用上大量天藍色和深黑色,當中更見幾抹强烈的紅色作點綴,凸顯了這幅頂級鉅作的與衆不同。四十年前,白髮一雄將自己懸吊在畫布上方來回擺蕩,用足踢抹及摔摜顔料作畫,開創先河。創於四十年後的《海炎》與藝術家最早期的抽象表現主義作品一樣,呈現出充滿力量,攝人心魄的激情動態。畫中對比鮮明的顔色似乎陷入了交纏搏鬥,在畫布上形成强烈的視覺張力。儘管如此,白髮一雄寬闊鬆散的筆觸,卻又散發著自然的優雅氣息,讓人想起日本古典書法傳統。本作曾在千禧年前後多個備受好評的白髮一雄展覽中展出,其中包括日本神戶市兵庫縣立美術館、英國倫敦的Annely Juda Fine Art畫廊以及東京畫廊的展覽。

《海炎》在日文中原意為「大海的深度」,畫中澎拜激烈,生機勃勃的色彩,讓人回想起深不見底的大海,憶起深邃神祕的大自然力量。作品近兩米高,畫布邊緣可見幾抹白色,像洶湧大海上瞬間即逝的泡沫一樣,迅速被清澈的藍色和剛勁有力的墨黑色取締,盤據中央。這團氣勢磅礴的色彩之中又存在幾撮隱隱若現的紅、紫色,在畫布上拉出空間深度,帶來張力,可見白髮一雄這些著名的「足繪」背後,是藝術家精湛嫻熟的非凡技巧。

白髮一雄出生於 1924 年,在兵庫縣尼崎市一個和服商人家庭長大,從小接觸日本傳統藝術、書法、古董、古典戲劇電影、浮世繪和中國古代文學。在京都學習日本傳統繪畫後,白髮一雄開始擺脫具像風格,向更富情感的藝術創作發展。在1950 年代初期,這代表挑戰傳統的藝術形式。白髮一雄的藝術之路扎根於百廢待興的戰後時期,他成爲具體派的著名代表。具體派為當時最受好評的新藝術運動之一,經歷過二戰期間的黑暗暴力,團體致力於突破藝術傳統,大膽創新。

1954 年,白髮一雄摒棄用畫筆作畫的傳統規限。反之,他將自己綁在繩子上,以足蘸濃稠的顏料,再豪邁地將顔料一層層踢抹、摔摜於畫布上。他並不滿足於把顏料潑或畫在畫布表面,而是藉著這種大膽狂放的創作方式,將自身沉浸到作品中去,透過身體和材料將內心的思想以激烈的方式宣洩出來。如此一來,他將自己與西方抽象表現主義的動勢繪畫區分開來,開闢了一種狂野原始的藝術表達方式。與在他之前的藝術家不同,白髮一雄的抽象藝術表演充滿激烈狂亂的動作,它們——「不只是身體的動作…… 物質亦隨之騷動起來。」(白髮一雄,摘自蔡宇鳴撰,〈Not just beauty, but something horrible〉,《身體與物質:白髮一雄與星野曉的藝術》展覽圖錄,紐約, 2015年,頁21-22)

雖然白髮一雄以人體取代畫筆的激進行為,讓外界將他與伊夫・克萊因(Yves Klein)等著名西方藝術家相提並論(伊夫・克萊因在 1961 年的《Anthropometries》中,利用裸體女性作為「人體畫筆」),但白髮一雄在藝術創作中,卻利用他整個身體與材料本身角力,並且喚醒材料原始的生命力。這種創作方式展現了戰後具體派藝術家的使命,他們將「工具」(gu)與「身體」(tai)融合在一起,從日本廣島原爆後的廢墟中毫不怯懦地站起來,在飽受戰火摧殘的國土上宣揚一種重新振作的「具體」哲學。白髮一雄曾說,他的藝術「不僅需要美感,還需具備一些令人震驚的元素」(摘自白髮一雄與蔡宇鳴對談,日本蘆屋市,1998 年);白髮一雄通過與暴力交涉並且超越暴力,「與纏繞他和他那一代人的夢魘搏鬥,同時為未來的歲月帶來希望」(《身體與物質:白髮一雄與星野曉的藝術》展覽圖錄,紐約,2015年,頁23)。

在白髮一雄的創作過程中,他的腳、身軀與心是無意識的載體,呈現直覺、隨興與心之所向,它們如一股強勁力道、嘶吼著想衝破畫框的限制。油畫顏料和藝術家的技巧結合起來,將想衝破畫框的能量拉回來,制衡它本能性的狂野。他巧妙處理顔料,並容許潛意識自由釋放,引導畫布上的抽象形狀作出循環動態,吸引觀衆注視,這些對立的力量共同賦予這部作品能量和深度。《海炎》畫面上兩道粗獷的黑色直立大筆,剛健如整體構圖之骨幹,反應白髮一雄對畫面安排的考量;然而此骨幹卻又蘊含彎曲的轉折與蜿蜒的色彩漸層軌跡,這則是用腳作為畫筆所產生的細膩變化。這種與生俱來的結構感,來自白髮一雄對形態和作畫技巧所具之深入理解,從而能成熟掌握畫面構圖,是他積累了四十多年的卓越藝術成果。

離開具體藝術協會後,白髮一雄不僅學佛,也重新開始學習傳統水墨書法,以拓展藝術風格和技巧。這段回歸本源的經歷,為他那標誌性的足繪藝術增添了幾分水墨神韻,點明了他的東方本源。這點在他的後具體時期作品中顯而易見,如《海炎》中鬆散的自然筆觸流露出優雅抒情,讓人想起日本古典書法傳統,以及大海澎湃萬千的磅礴氣勢。