A landmark literary rediscovery: the manuscript of Hemingway's longest and most-anthologized story

Hemingway biographer Michael Reynolds exuberantly announced the rediscovery of this manuscript when the family papers of Jane Mason were rediscovered and sold in the late 1990s: “Just when Hemingwayites thought it was safe to make critical judgements about the old man, these forty years interred, he continues to confuse us with messages from the grave. We thought we had seen all the manuscripts that would ever surface. With the exception of the infamous ‘lost manuscripts’ of 1922, all the novels and non-fiction manuscripts were accounted for. We had seen most of the first drafts of the stories, with the exception of ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber’ and ‘The Light of the World.’ The first is his most well known and often reprinted story… To have them here come to light is probably the most important event of the Hemingway Centennial which has been filled with Hemingway surprises” (introduction, Christie’s, “The Mason Family Discoveries,” Printed Books & Manuscripts, 19 May 2000).

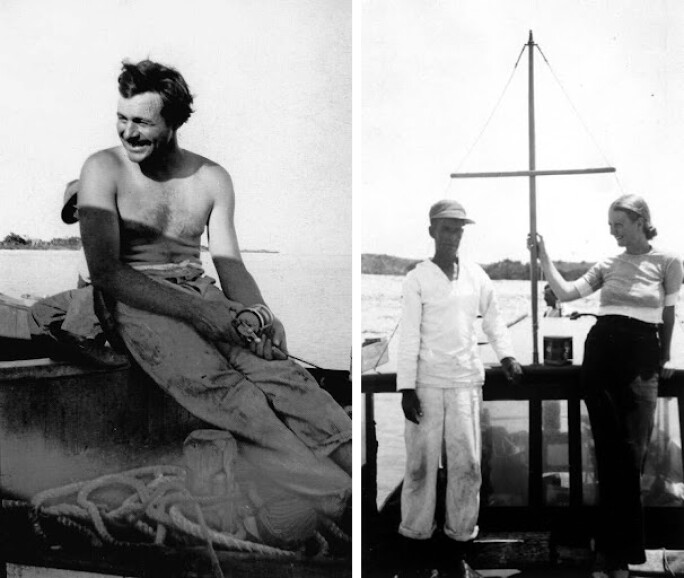

Hemingway had met the 22-year old Jane Mason in 1931 when returning to the United States on the Ile de France. They were attracted to each other, but both were married at the time: he to Pauline (his second wife), and she to Grant Mason, the head of Pan American Airways in Cuba. Their correspondence, also sold in the 2000 auction, revealed that they became fast friends and indeed Jane proved to be a muse for the author. She was the model for the deadly wife Margot in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and for Helene Bradley in To Have and Have Not. Aline Salierno Mason, Jane Mason’s granddaughter, discovered the Hemingway letters and manuscripts in old family steamer trunks, and wrote an account of their friendship, “To Love and Love Not,” published in the July 1999 issue of Vanity Fair. A selection of their correspondence was sold at Christie’s on 10 December 1999, prior to the more important offerings sold the following May.

RIGHT: Carlos Gutierrez and Jane Mason aboard Joe Russell’s boat “Anita”, 1933. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

“The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” “tells us more than we usually get from a Hemingway story. Breaking every ‘rule’ of short fiction, Hemingway shifts the point of view from the white hunter, to Francis, to the wounded lion. We know what everyone but the wife. Margot, thinks about the husband’s cowardly performance. Thus when her shot to ‘save’ Francis from the charging buffalo hits him ‘two inches up and a little to one side of the base of his skull,’ readers have never been able to resolve her intentions. This story was the centerpiece of the feminist attacks of the 1980s and has become central to second generation gender studies that are rehabilitating Hemingway’s reputation” (Reynolds).

One critic who explored these new approaches to Hemingway was Nina Baym, whose paper "Actually, I Felt Sorry for the Lion" in New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway stoked these debates for some time (Jackson J. Benson, editor, Durham: Duke UP, 1990. 112-20). Taking issue with critics who read Margot as an example of the stereotypical “bitch,” Baym describes a bond between the lion and Margot, arguing that the latter is innocent because of her identification with the lion as a victim of male domination and cruelty. The scholar George Cheatham demonstrated that this debate was far from over a decade after the publication of Baym’s paper: “In a recent revisionist reading, for example, Nina Baym argues two points in what she calls a critique of the ‘long-lived and monolithic’ critical view that ‘Hemingway's work is deeply antiwoman in its values’... Baym asserts first that ‘The Short Happy Life’ is marked by five speaking subject positions – an omniscient narrator, Francis Macomber, Margot Macomber, Robert Wilson, and the lion. The text thus illustrates what she calls ‘faceted narration’, a ‘play of narrative voices and points of view’, and thus, Baym continues, Margot Macomber's voice is not suppressed in Hemingway's text, despite Robert Wilson's final anxious attempt to silence her” (George Cheatham, “Margot Macomber’s Voice in Hemingway’s ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,’” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 83, no. 3/4, 2000, pp. 739–64).

Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum | Public domain via Wikipedia

Kenneth S. Lynn, in his biography of Hemingway, dedicated 5 pages to “The Short Happy Life” and illuminated its complex relationship with readers: “Except for ‘Big Two-Hearted River,’ no other work by Hemingway has been read so unrigorously so many times as ‘Macomber,’ and not merely because of the author’s own comments about it” (Lynn, Hemingway, New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1988, pp. 432-3). Lynn calls it “a fable about the perils of self-overcoming” in which “the doubt-haunted Macomber represents the Hemingway for whom the dark had always been peopled and always would be. Near the end of the fable, the doubter succeeds in winning the approval of the brute. He becomes, in short, the sort of man he is not, and pays for it with his life” (ibid, p. 436). A decade after he wrote it, Hemingway hid behind his own myth and, speaking with an interviewer, burdened the story with a misogynistic gloss. As later criticism evolved, it thankfully has been resurrected and appreciated for the much deeper and darker resonances, placing it among the handful of Hemingway stories that remain vital to the study of 20th century American letters.

“The last time a Hemingway autograph manuscript of this importance appeared at auction was in 1958 when the holograph manuscript of Death in the Afternoon was purchased for the University of Texas (for $13,000). As has been noted, with the discovery of the autograph manuscripts of "The Light of the World" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" all are now accounted for and the appearance of another is remote indeed. This is it!”

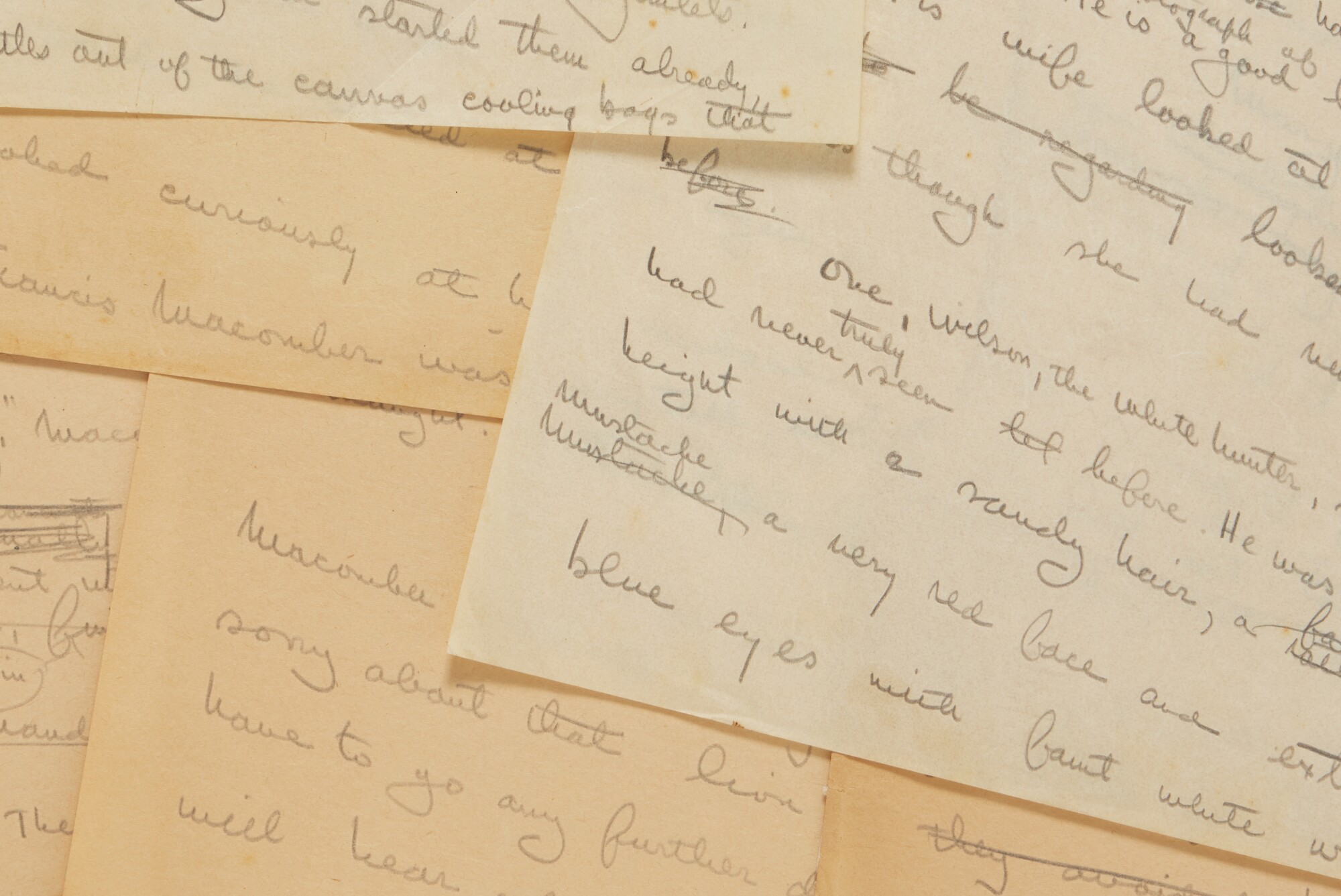

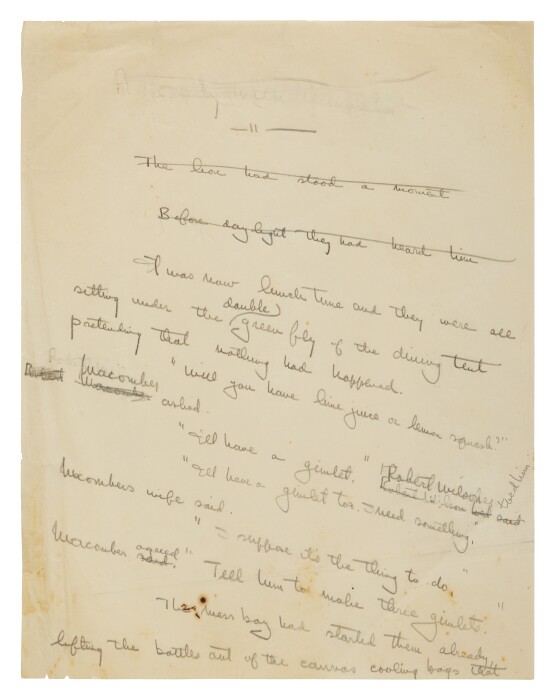

Hemingway wrote only two stories set in Africa and developed them at roughly the same time, with their rough ideas sketched in fall 1934 and their ultimate forms taking shape in spring 1936. “Macomber” and "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" were written at the height of his artistic powers, and Hemingway’s final printed text closely follows the manuscript. Whole pages are written with little or no revisions and the majority of changes involve descriptions of landscape or of characters: at pages 21-22 nearly a page of manuscript is crossed out; in several other places whole sentences are scored through and throughout the manuscript single words and phrases are altered. Two false starts are crossed out; and in the early pages Macomber's name changes from "Robert" to "Donald" before finally settling on "Francis" (perhaps a volley in his long standing rivalry with F. Scott Fitzgerald). There are extensive insertions – interlinear and continuing into margins – presumably added the next day after Hemingway read over his work. All of his writing –both first draft, revision, and insertion – is very readable.

Hemingway wrestled with the title. As seen in this image, he erased a drafted title, "A Comedy with Animals," at the top of the first page. In one letter he also refers to the manuscript as “The Happy Ending.”

Throughout the manuscript, whole pages are written with little or no revisions and the majority of changes involve descriptions of landscape or of characters. There are several places where whole sentences are scored through, such as the two false starts crossed out here on the first page.

In the early pages Macomber's name changes from "Robert" to "Donald" before finally settling on "Francis."

“Macomber” is one of Hemingway’s most impressive performances as a writer, with his lean style belying narrative and linguistic shifts of gymnastic proportions. Shifting points of view and temporal changes show Hemingway at work (replaced words are in brackets) in one remarkable passage: "He heard the [roar cara-wong] ca-ra-wong! of Wilson's big rifle, and again in a second crashing [roar] carawong! and turning saw the lion, horrible looking now, with half his head seeming to be gone crawling toward Wilson in the edge of the tall grass while the red faced man worked the bolt on the short ugly rifle and aimed carefully as another blasting carawong! came from the muzzle and the [great, pitiful] crawling, heavy, yellow bulk of the lion stiffened and the huge, mutilated head slid forward and Macomber, standing by himself, in the [field] clearing where he had run holding a loaded rifle, while two black men and a white man looked back at him in contempt, knew the lion was dead."

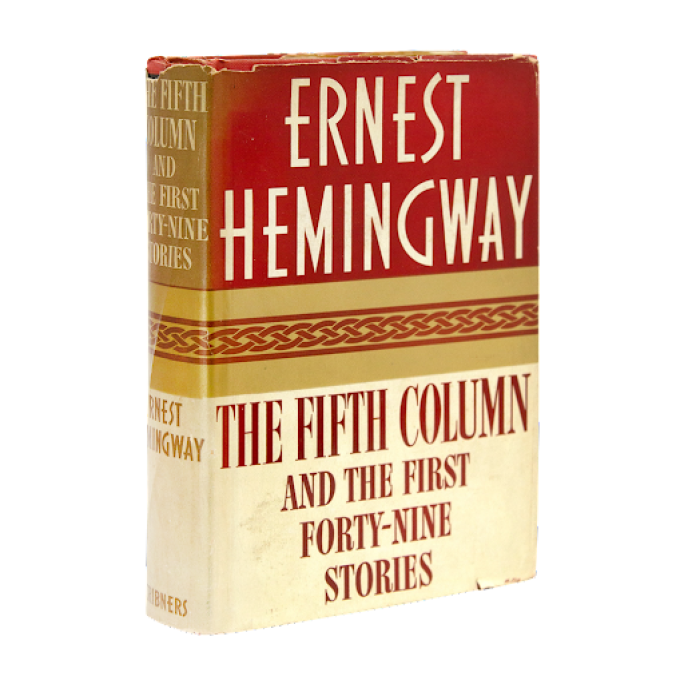

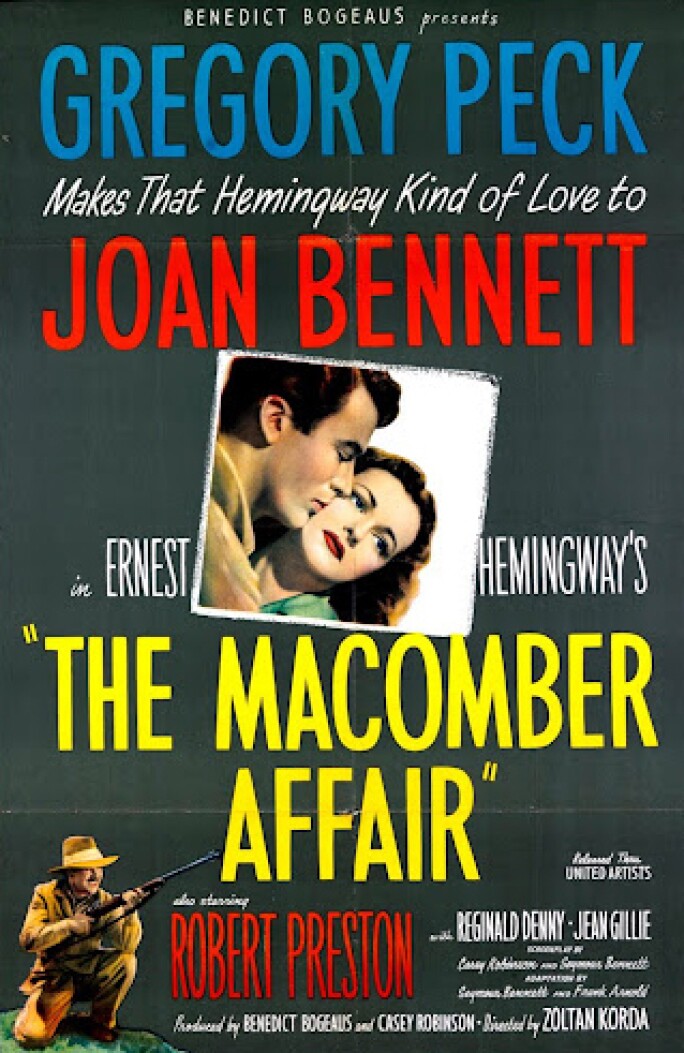

Aside from Francis’s name, Hemingway also wrestled with the title. He erased "A Comedy with Animals" at the top of the first page, and in one letter he refers to it as “The Happy Ending.” It is his longest story both in length of manuscript ("Big Two-Hearted River" is next) and printed text (beating "The Undefeated" by some three pages). "Macomber" was first published in Cosmopolitan (September 1936) and was then the opening story in the collection The Fifth Column and the First Forty-nine Stories (1938). It remains his most often reprinted story, a fact that Hemingway seemed prescient of in a letter to Max Perkins when he wanted to protect it: “In regard to the question of the Garden City Publishing Company reprinting ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,’ I am all against giving them permission to reprint it in a 69¢ edition. We, that is Scribner’s, and I, have never made any money from those four stories which headed off the collection I published [1938]. Sooner or later if we hang on to them they will make some money because the book they were published in never had any sale. I remember myself trying to buy a copy in Scribner’s just a couple of months after it was published and there not being one in the store” (8 July 1942, Selected Letters, p. 534). The Macomber Affair, a movie based on the work and with a script more faithful to Hemingway's text than most, was released in 1947.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0039591/mediaviewer/rm335232512/?ref_=tt_ov_i

Regarding other manuscripts of the story, Young and Mann 81 A-D list four autograph manuscript fragments, totaling 16 pages, of "an extremely early draft" at the John F. Kennedy Library; and Hanneman F6a locates a "corrected typescript, signed, 39 pages," at The Morris Library, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. "With the three stories of 1936 – 'The Capital of the World,' 'The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,' and 'The Snows of Kilimanjaro' – Hemingway 'reaches the threshold of his final phrase as a tragic writer' and crosses it into For Whom the Bell Tolls. All three stories approach the formal structure and emotional intensity of classic tragedy with characters who risk death in obedience to some primary drive and achieve something of a tragic transcendence" (Paul Smith in New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, p. 378).

When it last appeared at auction in 2003, legendary bookman Bart Auerbach noted that “The last time a Hemingway autograph manuscript of this importance appeared at auction was in 1958 when the holograph manuscript of Death in the Afternoon was purchased for the University of Texas (for $13,000). As has been noted, with the discovery of the autograph manuscripts of "The Light of the World" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" all are now accounted for and the appearance of another is remote indeed. This is it!” In the twenty years since, nothing of this significance has appeared on the market again. Truly a once in a generation opportunity.

PROVENANCE:

Antony Mason (Christie's New York, 19 May 2000, lot 302)