‘An Indian painter, brought up a strict Roman Catholic under Portuguese colonial rule, later a member of the Communist Party and now [1961] living in London: these are the barest details about one of the most gifted and original modern artists. Those writers on art who even today look upon all new painting as the result of age-old cultural roots, must be rather baffled by such a history, for it bears witness to a great number of contradictory influences which make nonsense of conventional ideas of tradition’.

John the Baptist, the forerunner of Christ, was famously rendered by the art greats of the sixteenth to nineteenth century - Titian, El Greco, Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Goya. Typically depicted in the wilderness in which he is known to have wandered and preached as a young man, the prophet is oft shown clad in just animal skins and stood in evangelizing postures. In the current lot, we see the baptist through the brutalizing lens of the Indian modern master Francis Newton Souza. With a crudely delineated and stylized form, this radical reimagining of the preacher, to borrow Edwin Mullins’ words, boldly upturns all ‘conventional ideas of tradition’. (ibid.)

Right: Current lot

Painted in 1963, the current lot was exhibited at Souza’s 1964 solo show at Grosvenor Gallery, London: The Human and the Divine Predicament. The catalogue was introduced by Mullins, the acclaimed art critic and author of the seminal Souza monograph, published just two years prior. Described by Mullins as ‘a brilliant anthology’ of the artist’s recent works, ‘a show of disguises and disparities’ (E. Mullins, The Human and the Divine Predicament, New Paintings by F. N. Souza, 1964, Grosvenor Gallery, London, unpaginated), this exhibition included some of Souza’s now most iconic and recognizable works. The show centered on the artist’s two seminal themes, ‘Sin and sensuality’ (ibid.), with the erotic curves of his female nudes depicted alongside the disfigured and stark forms of Souza’s saints and sinners of the Catholic faith. Since then, a number of paintings from the exhibition have featured at auction and achieved notable results, including the famed largescale work The Deposition, which sold in excess of $1.9 million at Sotheby’s London in 2016.

The pervading influence of Catholicism on the artistic iconography of Souza can be seen throughout his career, but his most significant and emotively charged religious works were executed in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Arguably, the most famous of all is The Crucifixion (1959), part of the Tate Gallery’s permanent collection, in which Souza represents the violent image of Christ upon the cross - “the impaled image of a Man supposed to the Son of God, scourged and dripping with matted hair tangled in plaited thorns”. (F. N. Souza, ‘A Fragment of Autobiography,’ F.N. Souza: Words & Lines, Villiers Publications Ltd., London, 1959, p. 10) Unlike in The Crucifixion or The Deposition, which are rendered with gestural paint strokes and vibrant palette, John the Baptist is duochromatic, with a coarsely applied ground of ochre pigment and the stark black outlines of the figure. Raw and stripped back, this strikingly austere representation recalls the ascetic character of the preacher himself. Set apart further still, he has not been deformed with the same monstrous stylization seen in the aforementioned works. The baptist retains the quintessential boldness of line for which Souza is famed, but is furnished with a dignity not often granted to the painter’s subjects.

Sotheby’s London, 27 November 2007, lot 411

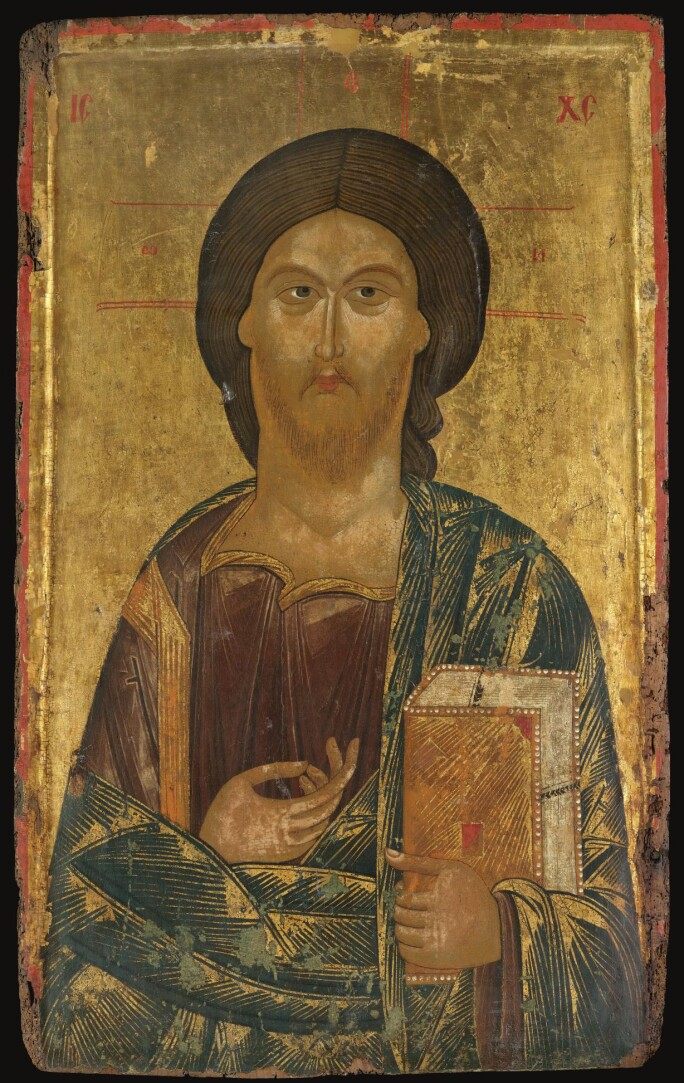

The influence of religion on Souza’s choice of subject and imagery converged with his knowledge and appreciation of broader artistic traditions. In the current lot, the posture of John the Baptist evokes the Byzantine iconography of Christ Pantocrator, with his right hand extended in blessing and his left holding a closed gospel. Meanwhile, in style, the rendering of the human figure can be related to both the expressive monochromatic studies of Goya or the bold and grotesque stylization of Picasso. Mullins notes Souza’s connections with these particular styles and artists, writing ‘He has never quite severed his links with Indian bazaar painting, with Indian erotic sculpture, and with South Indian bronzes… There still remains, too, a profound debt to Byzantium and to the Romanesque art of Spain, and there are further debts to El Greco, Goya, Picasso, Van Gogh and Soutine.’ (Mullins, The Human and the Divine Predicament)

This multitude of influences undoubtedly coalesced to inform Souza’s masterful understanding of form, color and expression. To say the artist was merely imitative would, however, do injustice to the unique virtuosity of this Indian master. To this end, the celebrated art critic and writer, John Berger, succinctly summates the genius of both the artist and his art:

‘he straddles several traditions but serves none.’