The mid-18th century was a golden age of English woodcarving, during which the increasing prosperity of the aristocratic and mercantile classes gave rise to an abundance of commissions to furnish either freshly constructed or newly renovated interiors of both town and country houses. This period also witnessed two of the most important aesthetic trends of 18th century English design, the rococo and chinoiserie, come into full fruition, amply demonstrated by the virtuoso carving and complex composition of this magnificent overmantel mirror.

The rococo style originated in France in the 1720s, its name deriving from the French term rocaille, meaning rock or shellwork, and drew its inspiration from the flora and fauna of the natural world. It was introduced to England in the 1730s through French immigrants like the draughtsman Hubert-François Gravelot and the Huguenot silversmith Paul de Lamerie, and by the 1740s had been taken up by the furniture designers Henry Copland and Matthias Lock, who began publishing engravings later collated in the 1752 New Book of Ornaments that proved highly influential in disseminating the new style in the production of mirrors, frames, tables and wall sconces.

The taste for chinoiserie was part of a European-wide fascination with exotic Chinese art that had begun in the seventeenth century with the importation of Chinese porcelain, lacquer, silk and later wallpaper through the East India trading companies. European artists integrated Chinese-inspired elements into their own designs for objects and interiors, and the fashion for such exotic motifs had reached an apogee by the 1750s, when it became almost obligatory for any residence of standing to have a Chinese bedroom or salon, and the bluestocking Elizabeth Montagu would write in 1749 that ‘we must all seek the barbarous gaudy gout of the Chinese’.

The artist most closely associated with the mid-century rococo style is the cabinetmaker Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779), whose 1754 compendium of designs The Gentleman and Cabinetmaker’s Director came to epitomize the new taste. His patterns for ‘Pier Glass Frames’ in plates 141-147 [fig. 1] incorporate many of the elements seen in the offered overmantel like the floral sprays, acanthus and C-scrolls, ho-ho birds and architectural niches and pavilions with Chinese figures, and these all became part of the standard ornamental repertory of numerous pier mirrors produced in the 1750s and 1760s [fig. 2].

Right: Fig. 2

Interestingly, among the drawings attributed to Chippendale that form part of the important group of his original sheets for the Director engravings now in the Metropolitan Museum include two designs that were not included in the final publication, one for an overmantel including hanging floral sprays [fig. 3] and another for a girandole frame suspended from a similar ribbon-tied floral garland [fig. 4].

Right: Fig. 4

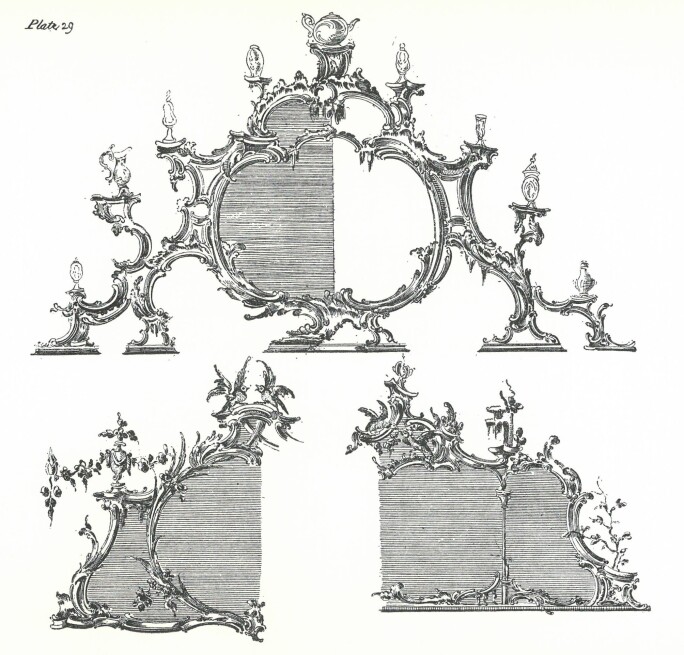

A contemporary of Chippendale also working in a similar manner was the London carver and gilder Thomas Johnson (1723-1799), who from 1755 began publishing designs for mirrors, chimneypieces, frames, girandoles and other ornamental objects ‘in the Chinese, Gothick and Rurarl Taste’, including two engravings of overmantels and chimneypiece surrounds related to the present example [figs. 5, 6], (reproduced in Helena Hayward, Thomas Johnson and the English Rococo, London 1964, plates 82-84, 92).

This overmantel is distinguished by the unusual detached ho-ho bird headed acanthus and c-scroll uprights flanking the oval frame, and it is likely the mirror formed part of Chinese room with comparable carved plaster decoration on the walls and ceiling. One of most celebrated incarnations of this type of room was the Chinese Bedroom commissioned by the 4th Duke and Duchess of Beaufort at Badminton House, Gloucestershire in c.1753, an early project of the Berkeley Square cabinetmakers William and John Linnell. The firm provided an entire suite of furniture including a pagoda-canopied state bed, armchairs, commode, two pairs of bedside tables and an overmantel mirror. Although no drawing for this mirror survives, other Linnell designs for overmantels that incorporate similar elements to the present lot including hanging floral sprays with bows are in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (several illustrated in Helena Hayward and Pat Kirkham, William and John Linnell, London 1980, vol. II, pp.60-63 figs.121-27). The entire Badminton suite was sold by the 9th Duke of Beaufort in 1921, with the bed entering the collection of the V & A, and the overmantel [fig.7] eventually acquired by the American heiress Doris Duke (sold Christie’s New York, 5 June 2004, lot 442). Several other overmantels similar to the Badminton model are recorded, including one formerly in the Untermyer Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art, and another formerly in the Hochschild Collection, sold Sotheby’s London 16 November 1984, lot 100 (illustrated in Graham Child, World Mirrors, London 1990, p.108 plate 154 and p.117 fig.154).

Right: Fig. 7