E mblematic of Tom Wesselmann’s pioneering exploration of iconography and media, Great American Nude #75 and 3-D Illuminated Drawing - Nude 1966 for Great American Nude #84 are iconic paradigms of the artist’s groundbreaking practice and the audacious innovation which defines the Abrams Family Collection. Celebrated today as one of the preeminent figures of the American Pop Art movement of the 1960s, Wesselmann indelibly influenced the aesthetic evolution and reception of figuration in the Twentieth Century. Of his myriad contributions to the trajectory of contemporary art, Wesselmann is best known for his historically and critically acclaimed Great American Nude series, which he began in 1961 and would ultimately comprise 100 works created over 10 years. The Great American Nude series epitomizes the best of Wesselmann’s creative acumen—masterfully synthesizing past and present through his compositions and, in a time where abstraction, redefining the purpose and potential of figuration. Exemplary of Wesselmann’s groundbreaking use of new media and materiality, Great American Nude #75 and 3-D Illuminated Drawing - Nude 1966 for Great American Nude #84 belong to a limited group of Wesselmann’s earliest illuminated molded plastic works. Synonymous with the innovations and originality of Wesselmann’s oeuvre, the series continues to be distinctly relevant today, inspiring subsequent generations of artists seeking to also reinterpret one of the most enduring subjects in art history: the female nude.

“It’s being involved in the excitement of an art that’s really contemporary—whether it’s pop, op, or the shaped canvas. These young painters are so filled with vitality and ideas—they’ve taken things around us and added something of their own. They’re giving us a new way to look at things, to notice what’s around us.”

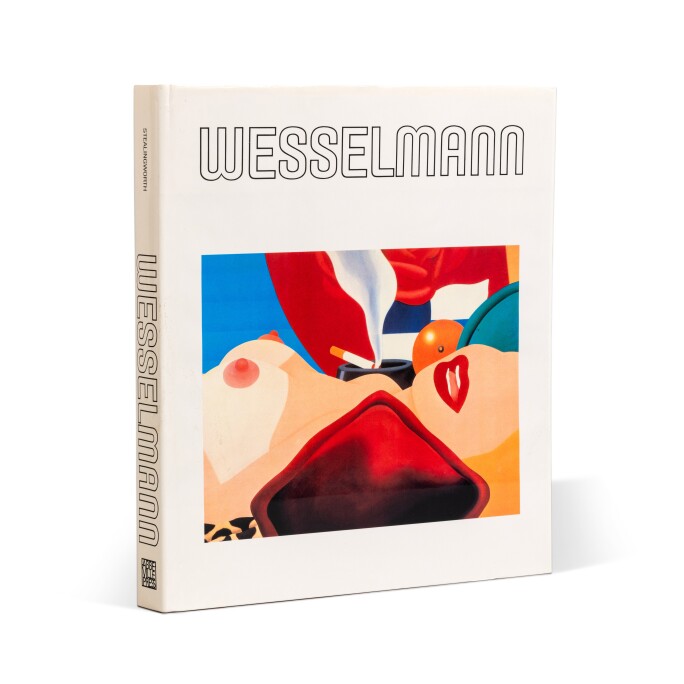

Both Harry and Bob Abrams considered Tom Wesselmann to be a dear friend, and they acquired several of his major works for their collection in the 1960s. Wesselmann worked intimately with Harry and Bob in the creation of the seminal 1980 monograph on the artist, published by Abbeville Press, which is today considered the most definitive text on Wesselmann’s career and practice. This monograph Tom Wesselmann, written by the artist himself under his established pseudonym “Slim Stealingworth,” includes a dedication to Harry for his profound impact on the artist: “a very dear man, who died before he could see this beautiful book finished.” Wesselmann goes on to further acknowledge the paramount roles of Harry Abrams and his son, Bob, in the creation of this groundbreaking publication. Wesselmann writes: “While this book was well in progress, Harry Abrams died. Harry and I started this book over ten years ago. It was a leisurely project on my part, constantly sustained by my long standing affection and regard for Harry. His experience, patience and support were much appreciated. His generosity of eye was matched by his generosity to the book. He met every request with ‘Tom, whatever you want.’ His attitude from the start was that it was my book and everything should be just as I wanted it. He was quite a man. With his death, his son, Robert, took over the project smoothly and the feeling of mutual involvement continued. I appreciate Robert’s feeling that it was a labor of love, as it certainly was for me” (Slim Stealingworth, Tom Wesselmann, New York 1980, p. 6).

Wesselmann’s accolades for Harry and Bob are testament to the Abrams family’s long-standing promotion of artists and creatives, their incomparable eye for quality, and their passion for the preservation and dissemination of beautiful and important artwork to the world. As early champions of Wesselmann, the Abrams family was fortunate to acquire landmark examples from the most highly regarded series of the artist’s career, a series that has become synonymous with the best of the Pop Art movement.

“Harry and I started this book over ten years ago. It was a leisurely project on my part, constantly sustained by my long standing affection and regard for Harry. His experience, patience and support were much appreciated. His generosity of eye was matched by his generosity to the book. He met every request with “Tom, whatever you want.” His attitude from the start was that it was my book and everything should be just as I wanted it. He was quite a man. …His son, Robert, took over the project smoothly and the feeling of mutual involvement continued. I appreciate Robert’s feeling that it was a labor of love, as it certainly was for me.”

Distinct amongst his peers, Wesselmann was uniquely indebted to centuries of art historical precedents, from canonical representations of the reclining female nude to the early Modernist’s use of collage and exploration of materiality. Within Wesselmann’s palimpsestic body of work, the viewer enters into dynamic dialogue with a wide range of references. His early paintings quote from the visual language of Titian’s Venus of Urbino, executed during the Italian Renaissance, and Edouard Manet’s groundbreaking masterwork, Olympia, which caused uproar at the 1865 Paris Salon. His works respond to the history of Picasso’s early Cubist works, liberally incorporating materials outside the scope of traditional painting. Wesselmann also cites the compositional arrangements of Henri Matisse, considering the ways in which the elements of a composition, such as “color, shape, line, texture,” interact to achieve and optimize the “visual intensity” of the work (Ibid., p. 17). Wesselmann’s paintings actively contrast the gestural rawness of the Abstract Expressionists like Willem de Kooning—an artist that Wesselmann greatly admired and once attempted to emulate—by asserting his commitment to figuration. In his reinterrogation of the Classical theme of the reclining female nude, Wesselmann contended with one of the most significant themes in the course of Western art history.

Great American Nude #75 is a remarkable example of Wesselmann’s eponymous series, executed at a time in which the artist once again explored and rearticulated his conception of painting through new media. In the earliest iterations of the Great American Nude series, Wesselmann’s women are cast against complex interiors, often punctuated by collaged elements and reproductions of canonical art historical works or American symbols like the stars, stripes, or flag. The women in these works are often depicted with flat planes of color, the curvature of their bodies defined by the shapes around them like Matisse’s infamous cut-outs. By the time Wesselman had worked on Great American Nude #75, he had distilled his iconography, refining the aesthetic components of his composition and perfecting his exploration of line and shape. The streamlined figure lounges back against a blue cushion, an orange star beaming behind her. Though Wesselmann eliminates the figure’s eyes, the viewer feels as if the figure is staring at them directly.

As with all of his early Nudes, Wesselmann limits his articulation of the figure’s faces and distinctive features in Great American Nude #75 and 3-D Illuminated Drawing - Nude 1966 for Great American Nude #84. Instead, Wesselmann depicts an archetype, referencing the genre of the reclining female nude and its inherent symbolism. Reactive in part to the changing attitudes surrounding sex and morality in American culture and in stark contrast to his art historical forebearers, Wesselmann’s women are liberated and openly eroticized. Throughout the series, Wesselmann depicts his women in brazen positions, accentuating certain elements of their anatomy and sensuality, but at all times maintaining their anonymity. As elucidated by the artist under his infamous pseudonym, Slim Stealingworth: “The figures dealt primarily with their presence. Almost all faces were left off because the nudes were not intended to be portraits in any sense. Personality would interfere with the bluntness of the fact of the nude” (Slim Stealingworth, Tom Wesselmann, New York 1980, p. 24). As the series evolved, Wesselmann explored various formats, eventually cropping the compositions, drawing attention to the inherent function of line and shape in the execution of an image.

Right: Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Image © Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt.

3-D Illuminated Drawing – Nude 1966 for Great American Nude #84 to the figure’s head and chest, conspicuously altering the parameters of the picture plane. Unlike the vast majority of the early Great American Nude works, 3-D Illuminated Drawing - Nude 1966 for Great American Nude #84 casts the figure against an anonymous oceanic background, interrupted only by plump, picturesque clouds, and a glimpse of the undulating shoreline. The present work is amongst the earliest in what would become a decades-long fascination with the seascape, carrying into other series within the artist’s output. Experimenting with the visual possibilities of perspective in both works, the figure feels disproportionately large, consuming the viewer’s vantage, as if the viewer is lying alongside her. Wesselmann’s inventive approach provides a novel alternative to the reclining nude, a symbol beyond the scope of portraiture, in a category entirely its own.

In 1965, Wesselmann would again make a radical shift and push the boundaries of his practice—rearticulating his conception of painting and breaking into the world of sculpture. Wesselmann began using vacuum-form plastic to create relief-like works with smooth, three-dimensional surfaces. Rather than incorporating the highly manufactured plastic elements he gathered from the world around him in the form of collage, as he had done with earlier Great American Nudes, Wesselmann transformed each composition into one of those three-dimensional objects itself. The process completely altered Wesselmann’s previous modus operandi. First, the artist sculpted his desired composition in a three-dimensional clay form, exploring his role as a sculptor, before ultimately casting the work in plastic. The result of this effort was a sleek, bulbous surface, a contemporary reinterpretation of the Classical relief, illuminated from within. Exemplars of this limited and significant exploration within Wesselmann’s practice, Great American Nude #75 and 3-D Illuminated Drawing - Nude 1966 for Great American Nude #84 encapsulate the ingenuity which distinguished Wesselmann as a leader within the theatre of twentieth century American art.