“I believe my paintings reflect our life. Our complexes and the idiosyncrasies of our people, with their rhythm and sensuality manifested in our music and dance; the sugarcane which alternately represents our misery as well as our wealth; our beliefs and superstitions; the inequality among races; the lack of integration between our economic situation and our psychology; and our climate and geography with their beauty and violence; the cacophony which characterizes our common condition.”

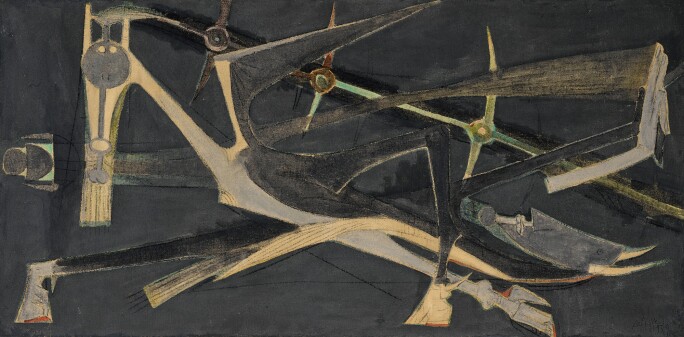

An exceptionally rare masterwork of unparalleled dynamism, Wifredo Lam’s Reflets d’eau of 1957 is one of the defining works of the artist's oeuvre. The culminating painting in a cycle of only four canvases executed in this monumental format, it is marked by the elusive hybrid symbology, elegant draftsmanship and rhythmic composition that are characteristic of Lam’s output in this critical period. Among the most iconic works of global modernism, Lam’s compositions from the 1950s subsume New World cosmologies within luminous, hybrid figures—plant, human, divine—that play out a vivid drama of transculturation.

Wifredo Lam's Totems

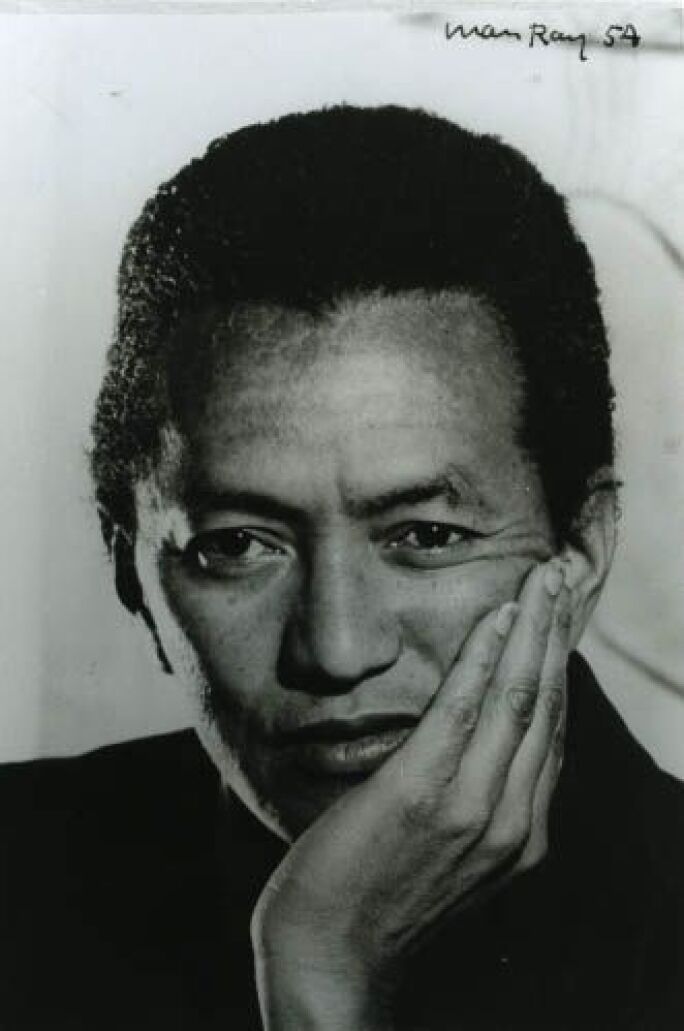

Born in Cuba to a Chinese father and a Congolese-Spanish mother, Lam embodied postcolonial hybridity not only in his work but in his essential identity. Having shown early artistic promise, he spent a long sojourn between Madrid and Paris from the 1920s to the early 40s, where he quickly fell in with avant-garde circles, eventually aligning with André Breton and the Surrealists. One of many artists forced to evacuate Europe during World War II, Lam landed first in New York, where he established a fruitful relationship with Pierre Matisse that would lead to many seminal exhibitions throughout the 40s—and finally returned to Cuba, a home unknown to him since childhood. Here he began a fertile period of rediscovery of Cuban and Afro-Antillean culture, landscape and cosmology.

In Cuba, Lam concretized the iconographic and stylistic idiom for which he is celebrated today; while the 1940s were dominated by vibrant color and evocations of glittering Antillean light, by the late 1950s Lam shifted towards compositional brevity; his palette is muted and his technique of execution simplified, revealing his extraordinary talent as a draftsman. Lam worked directly in charcoal on his prepared canvases, later reinforcing his compositions in oil but rarely revising them; Max-Pol Fouchet describes this extraordinary draftsmanship as “heightened plastic decisiveness, a handwriting endowed with clarity and dynamism” (Lowery Stokes Sims, Wifredo Lam and the International Avant-Garde, 1923-1982, Austin, 2002, p. 122). His crisp, sweeping lines contribute to an overall quality of clarity and understated elegance in these pictures, rendered in soft earth tones and rich blacks.

Reflets d’eau, like its three companion works, is dominated by a central stalk of sugarcane, the paradigmatic crop of the Caribbean—redolent at once of sweetness and the sinister legacy of plantation slavery and the triangle trade. For Lam, sugarcane is an essential Cuban image; it embodies the moral complexities of the region’s hybridity, it “alternately represents our misery as well as our wealth” (quoted in ibid., p. 114). The stalk of cane is studded with a rhythmic cadence of three key recurring motifs of Lam’s mature plastic vocabulary: sharp curvilinear elements, which can read as leaves or even as machetes, horned heads of Elegua, orisha of the crossroads who activates the pathway between the divine and the mortal, and soaring abakuá diamonds, symbols of fertility (see fig. 1).

We have completely separated ourselves from our own land, and have replaced its dynamism with a false sense of order that is derived from Europe...Wifredo Lam has come to show us our own essence. Are we able to see it?

Emerging darkly from the atmospheric umber of the background, a hooved figure dives behind the cane, extending two palms in a gesture of either warning or peace. The only work in the series to feature such a figure, it may even be an evocation of the artist himself, bearing some similarities to an allegorical self-portrait, Bonjour M. Lam executed two years later. The title, Reflets d’eau, adds a layer of conceptual complexity; while the other three are all titled as totems—concrete, embodied objects—the present work is a reflection: evanescent and mysterious, a captured trace of a brief moment in time. The present work can therefore be understood as a culmination of the series, and the ultimate triumph in Lam's quest to build a truly Antillean and deeply personal totem.

"I have never created my pictures in terms of a symbolic tradition, but always on the basis of a poetic incitement. I believe in poetry. For me it is the great conquest of mankind."

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved from great trees, usually cedar, by several Indigenous cultures along the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Symbols of a family’s clan origins, wealth and prestige, as well as the reputation of the carver, they also illustrate narratives in a highly stylized manner— whether to commemorate historic figures, to represent shamanic powers or to retell familiar myths about animals, people and supernatural beings. By the second half of the nineteenth century, indigenous artists began to carve smaller versions of these monumental poles for sale and export by traders from the United States, Canada and beyond. These sculptures began to circulate in Europe alongside the growing climate of interest in “Primitive” art led by artists like Picasso and movements like Dada and Surrealism.

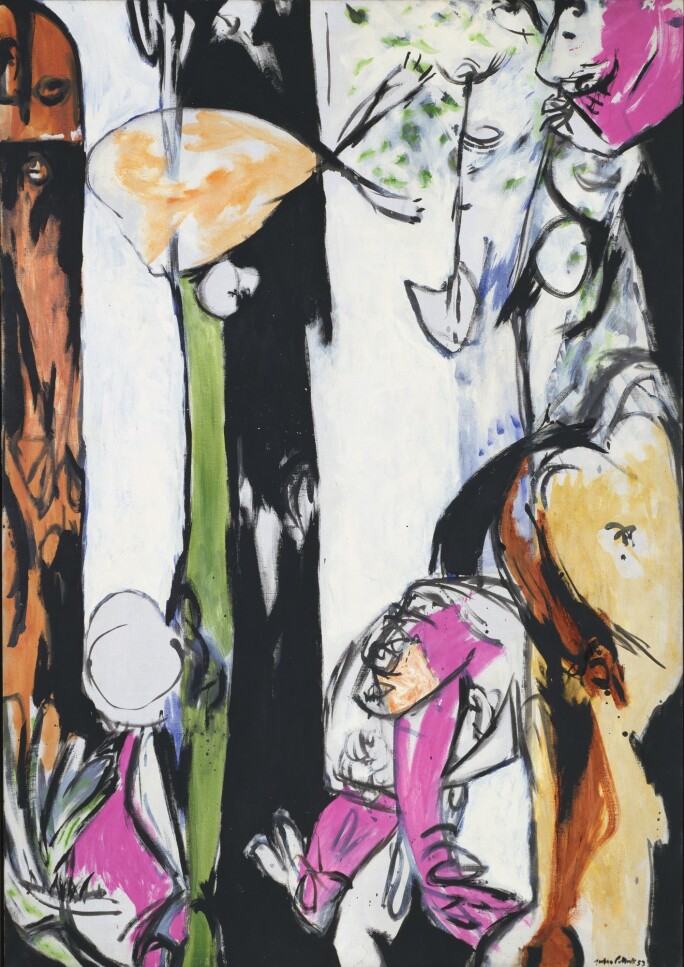

For the Surrealists in particular, who were preoccupied with explorations into the “essential” and “animal” aspects of the human psyche and who believed the world’s indigenous people to have a greater conduit to this essential human nature, both their graphic pictorial style and the animistic beliefs they represent had great appeal. The Austrian surrealist Wolfgang Paalen, a fellow exile from the war who fled first to New York and later to Mexico in the 1940s, was especially captivated by Northwest Coast cultures, writing extensively about the art of totem poles in the celebrated surrealist magazine DYN. The distribution of DYN within the now-international Surrealist network led many artists to respond to the concept and iconography of the totem, ranging from Lam to Max Ernst, Agustín Cárdenas, Gordon Onslow Ford and even Jackson Pollock.

Some, like Paalen and Pollock, distilled the totem into pure abstraction, bringing its psychic resonance to bear through meditation on pure form alone. Others, like Onslow Ford and Ernst, applied their own network of signs and symbols to it. For many artists of European and American descent, indigenous American and African artworks served as sources of inspiration primarily from a visual standpoint and their use of these objects can be interpreted as a colonial project; their historic knowledge of the true content and purpose of these works was often limited, and colored by their own artistic motives and thematic interests.

It irritated me that in Paris African masks and idols were sold like jewelry. In [my] works I have tried to relocate Black cultural objects in terms of their own landscape and in relation to their own world. My painting is an act of decolonization not in a physical sense, but in a mental one.

Lam, however, had a different project. An undisputed master of abstracted form and the visual languages of Picasso and Surrealism, he sought to use their interests in “Primitive” art from around the world to “affirm and define Black culture in Cuba, bringing it into the realm of ‘high’ art, rather than ethnographic amusement for the tourist industry. Lam saw his engagement of Afro-Cuban culture as an antidote to the ‘tourist degradation’ of the island and by its consequence: the degradation of Cubans of African descent. That he was aware of the subversiveness of his strategy was clear when he described himself as a 'Trojan horse'” (ibid., p. 140). In Reflets d’eau, Lam presents in towering stature a final, masterful totem to afro-cubanidad: a proud and decisively rendered image that documents and celebrates the identity in all its complexity, mystery and contradiction. Lam locates Afro-Cuban identity deeply within the Antillean landscape; the psychic and historic resonance of the sugarcane and the symbols that cascade down it are profoundly powerful.