“The painting must be fertile. It has to give birth to a world. It doesn’t matter if you see flowers in it, figures, horses, as long as it reveals a world, something living”

Sans titre (Soirée snob chez la princesse) dates from circa 1946, a time when Miró was rapidly gaining widespread international acclaim. Populated with highly stylised and abstracted figures, it uses the same vocabulary of signs that Miró had developed a few years earlier in his celebrated Constellations series (figs. 1 and 2). At once playful and enigmatic, the artist’s compositions of this decade are rightly among his most sought-after works, embodying his mature artistic vision.

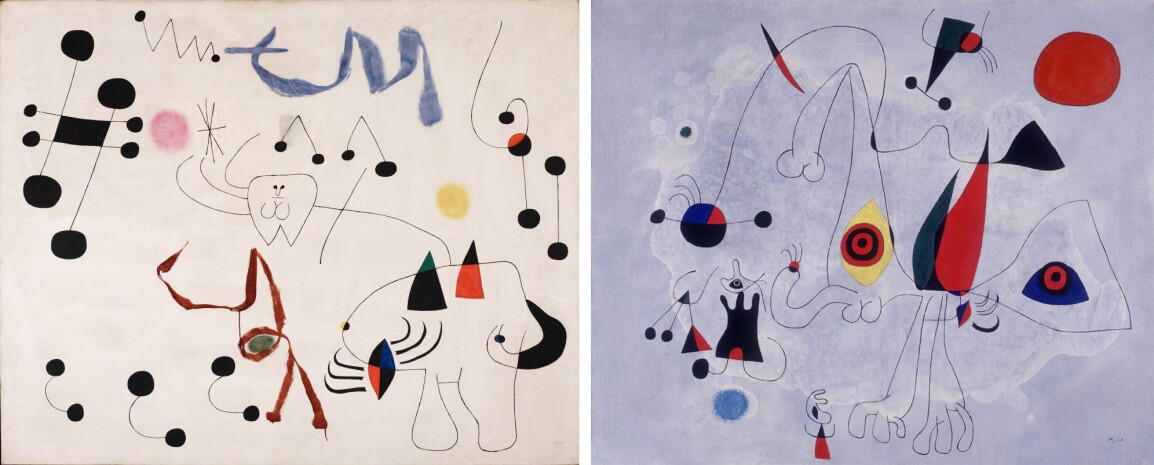

Right: Fig. 2, Joan Miró, Femme à la blonde aisselle coiffant sa chevelure à la lueur des étoiles, 5 March 1940, watercolour and gouache over graphite, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland © Successió Miró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS London 2024

In the present work, six brilliantly surreal characters, attending a 'soirée', as indicated by the title, are surrounded by Miró's signature stars and zig-zag lines. The clarity and spontaneity of the composition herald the new post-war style that Miró would also incorporate into his oils of this period (figs. 3 and 4) and are characterised by a joyful optimism.

“The space is taken up with big figures, birds, stars and signs. It is merely there to be occupied, and possesses no independent function of its own.”

Jacques Dupin discussed the compositional strengths of these oils from the 1940s, but his stylistic analysis equally applies to this particular work on paper: “The intimism of Miró’s entire production from 1939 on, and the invention of a new language which it made possible, lead to a magnificent series of large canvases painted in 1945, which are among the best-known and most frequently reproduced of all his works. They contributed greatly to Miró’s celebrity. Apart from two with black grounds, these works all have more or less uniformly light grounds, gray-white, blue-white, or blue. […] The space is taken up with big figures, birds, stars, and signs […]. Most of the figures are drawn in uniformly thin lines, with all the elegance we expect of Miró’s arabesque. Areas of pure color set off certain details or parts – legs, arms, or bust, but more often certain chosen elements by this means take on the value of signs – the eye, the female sexual organ, the foot. These canvases are thus fertile in ambiguity, for they may be read in two different ways. We may isolate figures and define them by their contours, their black or colored portions, their amplified details, in a space populated by signs and stars; but we may also read the painting in an over-all sense, grasping it as a rhythmic, chromatic ensemble in which all the accentuated elements – signs, stars, or attributes of figures – call to and answer one another. Actually, we read these works in both senses simultaneously” (J. Dupin, op. cit., 1962, pp. 378-379).

Right: Fig. 4, Joan Miró, Femme et oiseaux au lever du soleil, 1946, oil on canvas, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona (on loan from a private collection) © Successió Miró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS London 2024

The present work exemplifies the expressive power of images, even though they bear no faithful resemblance to the natural world. Miró is solely reliant upon the pictorial lexicon of signs and symbols that he had developed over the years. In fact, it was these compositions from the mid-1940s that would inspire the creative production of the Abstract Expressionist artists in New York. Miró populates this composition with several biomorphic stick figures, dressed in patches of primary colours. Floating against a background of pale green, these wide-eyed characters form a lively ensemble drawn from the boundless imagination of the artist. A few years after he executed this work, the artist offered creative advice to young painters, and his comments are an insight into the underlying motivations that inspired the present work: “He who wants to really achieve something has to flee from things that are easy and pay no attention to [...] artistic bureaucracy, which is completely lacking in spiritual concerns. What is more absurd than killing yourself to copy a highlight on a bottle? If that was all painting was about, it wouldn't be worth the effort” (quoted in Margit Rowell, Joan Miró, Selected Writings and Interviews, Boston, 1986, p. 226).

These works also offer insight into Miró’s evolving technique. As with his earlier Constellations, the sheet is first covered with a layer of pigment that brings out the paper texture to create a varied surface that seems to evoke an otherworldly skyscape. Whereas in the Constellations, Miró worked and re-worked the sheets in different colours to produce a multifarious backdrop, the compositions of the mid-1940s are simpler. In works such as the present, and the closely related gouache in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (fig. 5), the background places the figures in this same celestial realm, but there is more clarity and as such more focus on the spaces and interactions between them.

This creates a real sense of animation and movement in the present work, with the artist striking a perfect balance between image-signs and a pure abstraction; it is the result of active and ongoing improvisation that renders a precise interpretation impossible. By the 1940s Miró had started heightening his audience's engagement with his art by giving his pictures poetic titles. He had experimented with incorporating poetry or lyrical text into his pictures in the late 1920s, but then largely rejected the use of highly descriptive titles over the following decade. His return to using language as a didactic tool was a major shift in his art in the 1940s, and even in instances where he did not prescribe a title, they were often provided by his friends and supporters. This may have been the case in the present work, which has always been known by the wonderfully evocative title Soirée snob chez la princesse. As the inscription on the reverse indicates, the work was a gift from Miró to Louis Clayeux. Clayeux was artistic director at Galerie Maeght from 1948 to 1965 and close friend to many artists, including Alberto Giacometti, Ellsworth Kelly and Miró. The work then passed into the collection of Carlo Bilotti, an Italian-American cosmetics magnate who amassed a significant collection of art, some of which is now in the Museo Carlo Bilotti at the Villa Borghese in Rome.