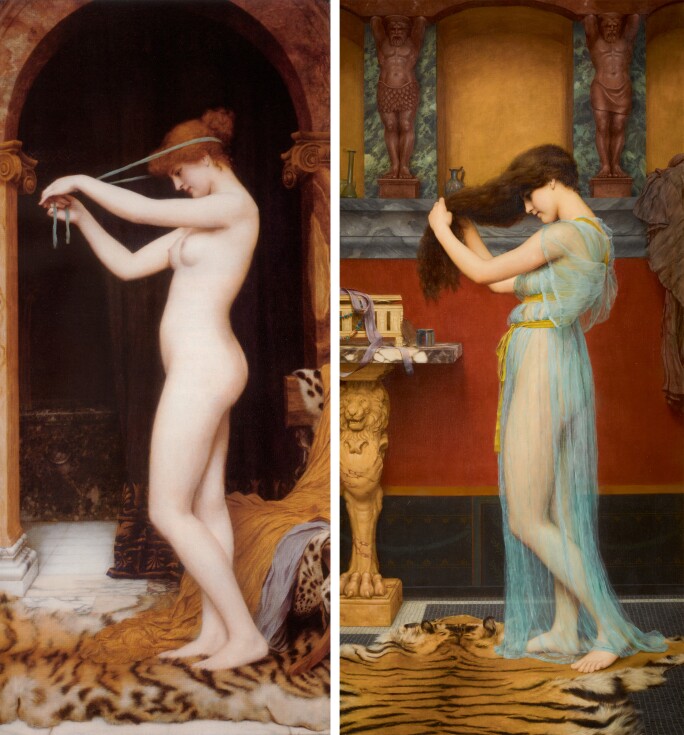

‘The beautiful concubine of Alexander with whom Apelles fell in love is shown as a delicately modelled nude standing with her sceptre before a wall of bronze. Her blue drapery rests on a ledge behind her and falls to her feet. Her head and shoulders are relieved against an elaborately worked circular mosaic of blue’

Warm, living, voluptuous flesh is contrasted with cold polished marble and mosaic, in Campaspe by John William Godward – one of the artist's largest and most ambitious paintings. Here is not a pale, tragic and fragile ingénue as may have been painted in the middle years of the nineteenth century, but a more red-blooded, confident woman of the end of the century – monumental, seductive and languorous. She is holding an ivory wand and her hair is bedecked with violets, flowers dedicated to Venus after she turned a group of Roman girls into a cluster of the little purple blooms after her son Cupid claimed that their beauty rivalled hers.

According to Pliny the Elder in Book XXXV of the Natural History, Campaspe (also known as Pancaste) was the most beautiful of the concubines of Alexander the Great. Desiring to have her immortalised Alexander commissioned the greatest of all classical artists Apelles to paint Campaspe. The resulting picture was said to have depicted the naked girl in the guise of Venus Anadyoneme (Venus wringing her hair after rising from the sea) and was both erotic and virtuous. The painting delighted and astonished Alexander but seeing how lovingly Apelles had painted Campaspe, Alexander realised that the artist's love for her was stronger than his own. Campaspe was released from her obligation to Alexander so that she could marry Apelles, an act of great generosity; 'For in thus conquering himself, not only did he sacrifice his passions in favour of the artist, but even his affections as well; uninfluenced, too, by the feelings which must have possessed his favourite in thus passing at once from the arms of a monarch to those of a painter.'

John William Godward was a quiet and ultimately tragic man (he committed suicide in 1922) but the bleakness of his solitary life is never hinted at in his pictures which depict a perfect and uncomplicated world of happiness and sunshine. His Classically-inspired world is not one of heroes and monsters, metamorphoses and curses – it is a world of ‘Dolce far Niente’ (the joyous state of pleasure in contented idleness) where pretty young girls wait for lovers on sunlit terraces or pose in bath-houses and vibrant gardens, aware of their beauty and proud to be admired. Godward was the son of an investment clerk and born into a conservative family living in Battersea in London. His family were not supportive of his ambition to become a painter but against their wishes he is believed to have studied 'rendering and graining' alongside fellow classicist William Clarke Wontner, probably learning to paint fake marble for fireplaces and furniture. Details of more formal artistic training have not been found but it is likely that he was a student at one of the many art schools in London, or possibly in Europe. In 1887 Godward had a picture accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy in London for the first time, a painting entitled The Yellow Turban. It was around this time that he began renting one of the Bolton Studios in Kensington in the heart of the London artist community. Godward continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy for almost two decades but by 1905 he felt that his style of painting was no longer receiving critical acclaim and he ceased to exhibit and sold his pictures through an agent and various art dealers. Despite his withdrawal from the public eye Godward enjoyed commercial success during his lifetime and the fact that he did not have to paint to please critics and the hanging committees of art galleries meant that he was able to paint what he wanted; the women in roman garb surrounded by beautiful objects and flowers.

Right: John Willian Godward, Campaspe

Godward was a great admirer of Greek and Roman sculpture and would often include examples in his paintings. He was also inspired by the languid poses of some of the marbles and bronzes he saw in museums. The pose of Campaspe was probably inspired by a statue of male beauty, the 2nd century Roman marble of Dionysus in the Louvre collection, which was based upon a Hellenistic original. The connection with the God of Wine is hinted at in the marble roundel behind Campaspe, depicting a naked priest of Dionysus making a votive offering at a shrine. This was probably a re-interpretation of the 1st or 2nd century AD Dionysiac Roman relief in the British Museum which had appeared in the background of Godward’s Clymene of 1891 (private collection) and in an adapted form in The Tambourine Girl of 1906 (private collection).

Although the Louvre marble may have inspired the pose, the figure of Campaspe was based upon a real woman, Florence (Florrie) Bird. Florrie was a professional model who worked at the Royal Academy Life Drawing Schools and posed for several artists, including another painter of classical subjects, Herbert Draper. Draper painted her in The Lament for Icarus in 1898 (Tate) and as a similarly monumental nude in his large painting of 1900 The Gates of Dawn. She certainly posed for Godward in 1896 when he painted Thoughts Far Away which is subtitled Portrait of Miss Bird (location unknown). Godward employed professional models for his paintings – including Ethel Warwick and the famous Pettigrew sisters – as he felt that they were better able to hold the strenuous poses he often demanded and that they were not reluctant to pose naked. The choice of a professional model for the figure of Campaspe is more than apt.

The fact that Campaspe is leaning against her own diaphanous robes and the ribbons which had bound them around her now exposed form, adds to the eroticism of the painting as they suggest the undressing of a real woman rather than the perpetual nudity of nymphs and goddesses. A comparable painting of 1898 entitled Circe, depicting the voluptuous sorceress of Aeaea from the Iliad, depicts a similarly posed nude in an exotic interior. Although this painting is now lost, other examples of large nudes by Godward include Venus Binding Her Hair and the Delphic Oracle (Christie's, London, 3 June 1994, lot 153). In the same period, he also exploited the erotic suggestion of pale flesh being visible through transparent togas, in pictures such as Mischief and Repose of 1895 (J. Paul Getty Museum of Art, Malibu), A Fair Reflection of 1899 (private collection) and Preparing for the Bath in 1900. This group of pictures share a monumentality of scale and a focus upon statuesque naked or near-naked women. It would seem that at this period Godward was seeking to impress reviewers by painting large-scale nudes and Campaspe was indeed well received at the Royal Academy Summer exhibition of 1896 and was celebrated by the writer A.G. Temple; ‘J.W. Godward, too in his straightforward and clear delineation of form so wholesomely academic in its workmanship has instanced his uncommon capacity in many examples, of which few are finer than the ‘Campase’ [sic] of 1896’.1

RIGHT: John William Godward, Preparing for the Bath, 1900. Oil on canvas, 161 x 77 cm. Private Collection. © Sotheby's

Godward’s agent Thomas McLean was in a state of confusion when he was asked to find a buyer for Campaspe, unsure which of Godward’s beautiful maidens she was; ‘You give such classical names to your pictures I don’t know which is Campaspe’.2 Godward had left visual clues to the identity of Campaspe but the vague classical iconography is indicative of late nineteenth century interpretation of mythology and history which was adapted to suit the motives of patrons and painters. Thus the titles are interchangeable and the primary effect of the pictures is decorative rather than narrative or archaeological. The pair of carved sphinxes and the marble medallion of a nude male reveller add to the archaic exoticism of the painting and give the nude a historic context. They also suggest the splendour of Alexander’s court, a lavishly decorated pleasure palace at Larissa in Thessaly. Whilst the subject of Campaspe was a well-known one and appears throughout art history, from Tiepolo to David, Godward was probably not thinking of a particular example when he painted his picture.

Campaspe was sold by Arthur Tooth & Sons in 1898. No record has been found of it again until it appeared at auction in 1936 following the death of Herbert Sanders Sanders-Clark the wealthy owner of Wilkinson, Heywood & Clark, specialist paint and varnish manufacturers to the railways and contractor to the Royal Navy. It is likely that the painting was inherited by Sanders-Clark’s wife, Elsa daughter of the German artist Hermann Schmiechen. Elsa’s step-father was Zachary Merton (1843-1915) who was in partnership with his brother Emile Ralph Merton as successful metal merchants. Emile owned John William Waterhouse’s magnificent Flora and the Zephyrs (offered in these rooms 6 November 1996, lot 307). Having no children of his own, it seems that Zachary bequeathed Campaspe to Elsa in 1915 and it remained with her and her husband until their deaths in 1933 and 1934. The Sanders-Clark collection included three significant nineteenth century paintings, Water Pets by Alma-Tadema (Christie's, New York, 30 October 2002, lot 38) and Biblis by William Bouguereau (Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad, India) depicting a nude girl gazing at her reflection in a pool. However the treasure of the collection was Venus Verticordia by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, Bournemouth), one of the most famous and beautiful female nudes painted in the Victorian period.

At the 1936 sale the buyer of Campaspe was 'Sampson', almost certainly John 'Jack' Sampson who had inherited his father, William Walker 'Bill' Sampson's business The British Galleries in 1930. The Sampsons purchased over two-thirds of the paintings by Godward auctioned in the first half of the twentieth century. Among the hundreds of paintings that passed through their hands at this time were many great Victorian masterpieces sold when they were at their lowest ebb in popularity. Many of the paintings went abroad and Campaspe was purchased by a collector in Kathmandu and it subsequently found its way to another collection in Asia. More recently the picture has found its way closer to home.

1 Temple 1897, p. 371.

2 Swanson 1997, p. 56.