The state ratification that ensured the success of the United States Constitution and inspired the Federal Bill of Rights: an official and attested copy of the form of ratification adopted by the Virginia Ratification Convention, together with a Declaration of Rights and a set of twenty amendments to the Constitution proposed by the Convention.

This official record of the final, critical days of the Convention is evidently one of just three surviving from the twelve sets ordered to be engrossed, signed by the president and secretary, and sent to each of the other state executives or legislatures. The Convention also ordered the amendments and form of ratification to be sent to the Confederation Congress.

Among the stirring resolutions and assertions recorded in the present document are a call for "a Declaration of Rights asserting and securing from encroachment the great principles of Civil and Religious Liberty, and the unalienable rights of the people"; the contention that "among other essential Rights, liberty of Conscience and of the Press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States"; and—most significant for the business of the Ratification Convention—the proclamation that "whatsoever imperfections may exist in the Constitution, ought rather to be examined in the mode prescribed therein, than to bring the Union into danger by a delay."

The Virginia Ratification Convention—also known as the Virginia Federal Convention—was called to meet at the State House in Richmond on Monday, 2 June 1788. The 170 delegates included the flower of the founding fathers from the Old Dominion: James Madison, Patrick Henry, George Mason, George Wythe, Edmund Randolph, James Monroe, Benjamin Harrison, Henry Lee, John Carter Littlepage, John Marshall, Humphrey Marshall, Burwell Bassett, Theodorick Bland, Bushrod Washington, and John Blair among them. On the first day of the Convention, Edmund Pendleton was unanimously elected president, and John Beckley was appointed secretary. Augustine Davis, the official printer to the Convention, was directed to print for the use of the delegates 200 copies of the Constitution proposed by the Constitutional Convention concluded at Philadelphia some nine months earlier.

The Virginia Ratification Convention was called in response to the recommendation of the Philadelphia Convention that the proposed Constitution “be submitted to a Convention of Delegates, chosen in each State by the People thereof, under the recommendation of its Legislature, for their assent and ratification. …” Twelve of the thirteen original states held ratifying conventions, Rhode Island only demurring (and not acceding to the Constitution until it had been the law of the land for nearly two years).

On 23 May 1788, ten days before the Virginia Convention first convened, South Carolina became the eighth state to ratify the Constitution (preceded, in order, by Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Maryland), making the timing of the Virginia’s deliberation especially critical. The Philadelphia Convention had decreed that Constitution would become the supreme law of the United States after approval by only nine of the thirteen states. This provision alone stamped the Constitution as a radical document: as William Starr Myers observed, “This was a direct breach of constitutional law since the Articles of Confederation had provided that any change or amendment in them must be ratified by unanimous vote by all the thirteen states. From a legal standpoint this amounted to a revolution as great as the rebellion against Great Britain, or the Declaration of Independence. Even when the new government became established and Washington became President in 1789, North Carolina and Rhode Island had refused their consent and did not ratify the Constitution until some months later.”

The Virginia delegates were sharply divided on the question of ratification. The Federalist faction, which favored the adoption of the Constitution, was led, unsurprisingly, by James Madison, who as a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention largely set the agenda by introducing the “Virginia Plan” and who subsequently orchestrated many of the key compromises necessary in drafting the Constitution itself. (Indeed, in his cover letter transmitting the Constitution to Arthur St. Clair, the President of Congress, Washington stressed the spirit of compromise that forged the Constitution: “In all our deliberations on this subject we kept steadily in our view, that which appears to us the greatest interest of every true American, the consolidation of our Union, in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence. This important consideration, seriously and deeply impressed on our minds, led each State in the Convention to be less rigid on points of inferior magnitude, than might have been otherwise expected; and thus the Constitution, which we now present, is the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensible.”) Madison also provided vital support for ratification in New York as well as Virginia as one of the three pseudonymous authors, with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, of the Federalist essays.

Patrick Henry, fearing federal encroachment on Virginia’s state liberties and government, eloquently headed the Anti-Federalist bloc of delegates. Henry’s opposition to government under the Constitution rather than the Articles of Confederation remained so zealous that he declined appointments as Secretary of State and as a justice of the Supreme Court. Henry’s control of the Virginia legislature also allowed him to thwart Madison’s election to the United States Senate, and Virginia sent William Grayson and Richard Henry Lee, two Anti-Federalist senators, to the First Congress. (Madison was elected to the House of Representatives.)

The Virginia Ratifying Convention met six days a week from 2 to 27 June, a total of twenty-three sessions. After some preliminary business, the vast majority of daily assemblies—from 4 to 25 June—were devoted to debating the Constitution in the Committee of the Whole, usually chaired by George Wythe. Although the Convention had resolved on 3 June that the entire Constitution was to be read and discussed clause-by-clause before any debate on ratification would take place, this provision was largely observed in the breach, with Patrick Henry in particular delivering discursive orations of up to three hours on the Constitution in general. Henry was supported in the debates by George Mason, James Monroe, and William Grayson.

In addition to James Madison, significant Federalist speakers included Edmund Randolph, George Nicholas, Edmund Pendleton, Francis Corbin, John Marshall, and Henry Lee. Randolph is the most intriguing of those supporting the adoption of the Constitution since, as a delegate to the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention, he was one of three members remaining at the Convention on its final session who declined to sign the Constitution. (The other two were fellow Virginian George Mason and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts. The two other delegates from Virginia, James Madison and John Blair, did subscribe their names to the charter.) Indeed, the debates at the Convention were dominated by a relative handful of delegates; 149 of the 170 attendees evidently never spoke during the meetings of the Committee of the Whole.

One of the principal points of contention between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists was the question of when the Constitution might be amended, particularly by the addition of a Bill of Rights. The Federalists wanted to ratify the Constitution unconditionally as proposed by the Philadelphia Convention and then address the adoption of such amendments as seemed appropriate and necessary; the Anti-Federalists favored ratification only after a consensus among the states agreed to implement the amendments they believed to be essential, specifically those deemed a Bill of Rights.

Throughout the debates in Virginia, neither side seemed to have a clear path to victory, with many delegates believing that the Convention was exactly divided on the question of ratification. On the nineteenth day of the Convention, 24 June, George Wythe proposed that the delegates “should ratify the Constitution, and that whatsoever amendments might be deemed necessary, should be recommended to the consideration of Congress which should first assemble under the Constitution, to be acted upon according to the mode prescribed therein” (Ratification, Virginia 3:1473). Patrick Henry countered with a proposal “to refer a declaration of rights, with certain amendments to the most exceptional parts of the Constitution, to the other States in the Confederacy, for their consideration, previous to its ratification” (Ratification, Virginia 3:1479).

The following day, George Nicholas called for Wythe’s resolution to be voted upon, and John Tyler moved the same action on Henry’s proposal. With Edmund Pendleton presiding, the Committee of the Whole rejected Patrick Henry’s resolution by a vote of 88 to 80 and voted to ratify the Constitution by the nearly identical vote of 89 to 79. The Federalists carried the day by appealing to perhaps the greatest element of the Constitution: its provision, outlined in Article V, for amendment. Indeed, even outside of Virginia the charter was adopted and eventually ratified on the expectation that it would almost immediately be amended by the addition of a Bill of Rights. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote half a century later in Democracy in America, “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.” The fact that George Washington, the most celebrated and admired Virginian of all, had presided at the Constitutional Convention likely swayed some votes as well.

“The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.”

In the last speech prior to the voting on these resolutions, 25 June, Edmund Randolph explained the change in his position on ratification since he had refused to sign the Constitution in Philadelphia, 17 September 1787: “The suffrage which I shall give in favor of the Constitution, will be ascribed by malice to motives unknown to my breast. But although for every other act of my life, I shall seek refuge in the mercy of God—for this I request his justice only. Lest however some future annalist should in the spirit of party vengeance, deign to mention my name, let him recite these truths,—that I went to the Federal Convention, with the strongest affection for the Union; that I acted there in full conformity with this affection; that I refused to subscribe; because I had, as I still have, objections to the Constitution, and wished a free inquiry into its merits; and that the accession of eight States reduced our deliberations to the single question of Union or no Union” (Ratification, Virginia 3:1537).

The crucial votes taken after Randolph’s dramatic final words are recorded on the first two pages of the present official document:

”Mr. President resumed the Chair and Mr. [Thomas] Mathews reported, that the Committee had, according to order, again had the said proposed Constitution under their consideration and had gone through the same, and come to several Resolutions thereupon, which he read in his place and afterwards delivered in at the Clerk’s table, where the same were again read and are as followeth;

“Whereas the powers granted under the proposed Constitution are the gift of the people, and every power [lacuna: not] granted thereby remains with them, and at their will; no right, therefore, of any denomination can be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by the Congress, by the Senate or House of Representatives, acting in any capacity, by the President, or any Department or Officer of the United States, except in those instances in which power is given by the Constitution for those purposes: And among other essential Rights, liberty of Conscience and of the Press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States;

“And, Whereas any Imperfections which may exist in the said Constitution ought rather to be examined in the mode prescribed therein for obtaining Amendments, than by a delay with a hope of obtaining previous amendments, to bring the Union into danger;

”Resolved, that it is the opinion of this Committee, that the said Constitution be ratified.

“But in order to relieve the apprehensions of those who may be solicitous for Amendments,

“Resolved, that it is the opinion of this Committee, that whatsoever Amendments may be deemed necessary be recommended to the consideration of the Congress which shall first assemble under the said Constitution, to be acted upon according to the mode prescribed in the fifth article thereof.

“The first Resolution being read a second time, a motion was made, and the question being put to amend the same, by substituting in lieu of the said Resolution and it’s [sic] preamble, the following Resolution;

“Resolved, that previous to the ratification of the new Constitution of Government recommended by the late Fœderal Convention, a Declaration of Rights asserting and securing from encroachment the great principles of Civil and Religious Liberty, and the unalienable rights of the people, together with amendments to the most exceptionable parts of the said Constitution of Government, ought to be referred by this Convention to the other States in the American Confederacy for their consideration;

“It passed in the negative Ayes 80 | Noes 88

“And then the main question being put, that the Convention do agree with the Committee in the said first Resolution;

“It was resolved in the affirmative Ayes 89 | Noes 79.”

After the Convention approved ratification without Patrick Henry's conditions, a committee of five—Federalists James Madison, Edmund Randolph, George Nicholas, John Marshall, and Francis Corbin—was appointed to compose the official text of Virginia’s ratification. The document submitted by the committee was adopted by the full Convention the same day, and is inscribed on the third and fourth pages of this official transcription:

“Virginia, towit:

“We the Delegates of the People of Virginia duly elected in pursuance of a recommendation from the General Assembly, and now met in Convention, having fully and freely investigated and discussed the proceedings of the Fœderal Convention, and being prepared as well as the most mature deliberation hath enabled us, to decide thereon, Do, in the name and in behalf of the People of Virginia, declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression, and that every power not granted thereby remains with them and at their will: that therefore no right of any denomination can be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified, by the Congress, by the Senate or House of Representatives acting in any capacity, by the President or any department or officer of the United States, except in those instances in which power is given by the Constitution for those purposes: and that among other essential rights, the liberty of conscience and of the press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States.

“With these impressions, with a solemn appeal to the Searcher of hearts for the purity of our intentions, and under the conviction, that, whatsoever imperfections may exist in the Constitution, ought rather to be examined in the mode prescribed therein, than to bring the Union into danger by a delay, with a hope of obtaining amendments, previous to the ratification;

“We the said Delegates, in the name and in behalf of the People of Virginia, Do by these presents assent to, and ratify the Constitution recommended on the seventeenth day of September, one thousand seven hundred and eighty seven, by the Fœderal Convention, for the Government of the United States; hereby announcing to all those whom it may concern, that the said Constitution is binding upon the said People. …”

At the same time that a committee was appointed to prepare a form of ratification, a larger committee comprising both Federalists and Anti-Federalists was directed to prepare a roster of recommended amendments. Chaired by Federalist George Wythe, the committee included the most prominent voices of the Convention, including Patrick Henry, Edmund Randolph, George Mason, James Madison, and James Monroe.

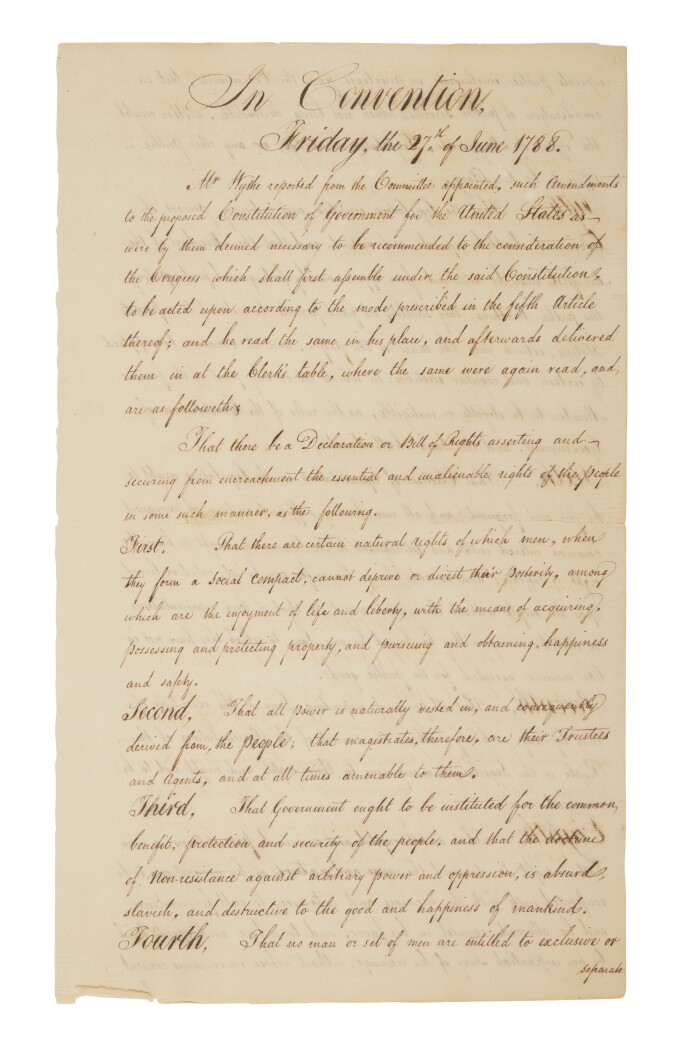

On the final day of the Convention, 27 June, Wythe reported “such Amendments to the proposed Constitution of Government for the United States, as were by them deemed necessary to be recommended to the consideration of the Congress which shall first assemble under the said Constitution, to be acted upon according to the mode prescribed in the fifth article thereof. …”

The amendments were presented in two tranches of twenty each: the first twenty comprising “a Declaration or Bill of Rights asserting and securing from encroachment the essential and unalienable rights of the people,” and the second roll of twenty embracing structural amendments in addition to the those in the proposed Declaration of Rights. Both sets of proposed amendments closely reflected the work of an Anti-Federalist committee chaired by George Mason in the early days of the Convention. (Mason’s committee was in close contact with New York Anti-Federalists and shared a copy of its proposed amendments with them.)

Virginia was not the only state to ratify the Constitution with the understanding that amendments providing for a Bill of Rights would be adopted almost immediately; the various ratifying conventions put forth a substantial number of proposals, ranging from South Carolina's four to New York's fifty-seven. But it is Virginia’s proposed “Declaration or Bill of Rights” that is most closely reflected in the federal Bill of Rights enshrined in the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

This is due largely to the efforts of James Madison, who less than nine months after the adjournment of the Virginia Ratification Convention was serving in the House of Representatives as part of the First Congress organized after the adoption of the Constitution. On 4 May 1789, Madison proposed in the House that debate begin on a series of amendments to the Constitution to serve as a bill of rights. Debate began on 8 June and was then referred to a select committee of eleven which, under the close guidance of Madison, created an initial draft that was presented to the House on 28 July. But that draft was presented in the form of revisions to the text of the Constitution itself, a confusing and ambiguous method that diluted the committee's charge: creating a clearly defined set of rights to be enshrined under the protection of the United States Constitution. On 24 August the proposals were more clearly stated and formatted as "Articles in addition to, and amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America … pursuant to the fifth Article of the original Constitution."

The House's proposed seventeen amendments were "printed for the consideration of the Senate," which, through debate and reconciliation, combination and elimination, produced a roster of twelve projected amendments, which was approved by the two houses of congress on 24 and 26 September 1789. Of the twelve-amendment Senate version, the ten amendments that became the Bill of Rights were the third through twelfth, officially ratified on 15 December 1791. (The second amendment proposed in both the seventeen- and twelve-amendment resolutions, mandating that any pay raises for Congress take effect only after an intervening election, was finally ratified in 1992 more than two centuries after it was proposed.)

" ... the Convention do in the name and behalf of the People of this Commonwealth, enjoin it upon their Representatives in Congress, to exert all their influence, and use all reasonable and legal methods to obtain a Ratification of the foregoing alterations and provisions in the manner provided by the fifth Article of the said Constitution ...”

It is principally due to Madison that the final directive of the Virginia Convention—"the Convention do in the name and behalf of the People of this Commonwealth, enjoin it upon their Representatives in Congress, to exert all their influence, and use all reasonable and legal methods to obtain a Ratification of the foregoing alterations and provisions in the manner provided by the fifth Article of the said Constitution”—was largely fulfilled. For the ideas and concepts in the Bill of Rights proposed by Virginia echo unmistakably throughout the first ten amendments to the Constitution:

“That in all criminal and capital prosecutions, a man hath a right to demand the cause and nature of his accusation, to be confronted with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence and be allowed counsel in his favor, and to a fair and speedy trial by an impartial jury of his vicinage, without whose unanimous consent he cannot be found guilty … nor can he be compelled to give evidence against himself” (Virginia eighth; Amendment V);

“That excessive bail ought not to be required nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted” (Virginia thirteenth; Amendment VIII);

“That every freeman has a right to be secure from all unreasonable searches and seizures of his person, his papers and property” (Virginia fourteenth; Amendment IV);

“That the people have a right peaceably to assemble together to consult for the common good, or to instruct their representatives; and that every freeman has a right to petition or apply to the legislature for redress of grievances” (Virginia fifteenth; Amendment I);

“That the people have a right to freedom of speech, and of writing and publishing their sentiments; that the freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty, and ought not to be violated” (Virginia sixteenth; Amendment I);

“That the people have a right to keep and bear arms: that a well regulated militia composed of the body of the people trained to arms, is the proper, natural and safe defence of a free State” (Virginia seventeenth; Amendment II);

“That no soldier in time of peace ought to be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, and in time of war in such manner only as the laws direct” (Virginia eighteenth; Amendment III);

“That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence, and therefore all men have an equal, natural and unalienable right to the free exercise of religion according to the dictates of conscience, and that no particular religious sect or society ought to favored or established by law in preference to others” (Virginia twentieth; Amendment I).

Many of the other proposals in the Virginia Declaration of Rights, while not specifically adopted, animate and confirm the founding sentiments of the United States. The first four rights enumerated by Virginia, taken as a whole, serve as a virtual preamble to the Bill of Rights: “there are certain natural rights of which men, when they form a social compact, cannot deprive or divest their posterity, among which are the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety. … all power is naturally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people. … Government ought to be instituted for the common benefit, protection and security of the people. … no man or set of men are entitled to exclusive or separate public emoluments or privileges from the Community, but in consideration of public services; which not being descendible, neither ought the offices of Magistrate, Legislator or Judge, or any other public Office to be hereditary.”

(The structural amendments proposed by Virginia dealt with matters like terms of office, reservation of powers, taxation and revenue, treaty ratification, jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, and even the publication of congressional journals. These structural amendments would have changed the nature of the Constitution and were not supported by Federalists, and, so, Madison did not recommend them in the House of Representatives.)

Virtually the final action of the Virginia Convention was the order to engross and distribute the present document and its fellows. In addition to this copy, two others are recorded, the copy sent to the Governor of Massachusetts (reproduced in Kaminski, et al., ed., Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia. Supplemental Documents, Part 2 [2019]). The other is in the Helen Marie Taylor Trust, currently on loan to the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond, Virginia. It has appeared at auction twice, but most recently thirty-three years ago: first in the Sang sales at Sotheby Parke Bernet, 20 June 1979, lot 843; then at Christie's, 17 May 1989, lot 312.

Although New Hampshire provided the necessary ninth state ratification of the Constitution just before the conclusion of the Virginia Convention, 21 June 1788, it is impossible to imagine that the compact would have held without the assent of Virginia. Not only was Virginia the most populous and wealthiest of the original thirteen states, New York, which ratified a month after Virginia did, 26 July, likely would have rejected the charter had Virginia done so.

This official record of Virginia's ratification, containing in its proposed amendments the nucleus of the Bill of Rights, placed the fledgling United States on a sure and secure footing.

Please note: all quotations in the above description from the proceedings of the Virginia Ratification Convention are taken from the present manuscript, with the exception of three that are attributed in the text to Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia (3).

Sotheby's is grateful to John P. Kaminski, Director of the Center for the Study of the American Constitution, University of Wisconsin, and co-editor of thirty-five volumes of The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution for reading and commenting on this description.

REFERENCE:

Richard B. Bernstein. Are We to Be a Nation? The Making of the Constitution. Cambridge, 1987

James F. Hrdlicka, Colonists, Citizens, Constitutions: Creating the American Republic. New York, 2020

Merrill Jensen, ed. The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution. Volume I: Constitutional Documents and Records, 1776–1787. Madison, 1976

John P. Kaminski, Gaspare J. Saladino, et al., eds. Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia (1). Madison, 1988

John P. Kaminski, Gaspare J. Saladino, et al., eds. Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia (2). Madison, 1990

John P. Kaminski, Gaspare J. Saladino, et al., eds. Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia (3). Madison, 1993

John P. Kaminski, et al., eds. Ratification of the Constitution by the States: Virginia. Supplemental Documents (part 2). Madison, 2019 (https://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?id=History.DHRCSuppVA2)

Pauline Maier. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. New York, 2011

PROVENANCE:

David Karpeles (purchased from Joseph Rubinfine American Historical Autographs, 1990)