“[…] the artist’s best late portraits seem to capture the sitter at the split second when his or her soul becomes visible”

Created in the final weeks of Egon Schiele’s life, Porträtstudie (Mädchenkopf) - Hilde Ziegler (Portrait Study (Head of a Girl) - Hilde Ziegler) captures a striking departure from the provocative, erotically charged figure studies that have long defined his reputation. Executed in black crayon, this frontal head study presents the portrait of seventeen-year-old Hilde Ziegler, meeting the viewer’s gaze with calm self-possession (fig. 1). The drawing is one of two known portraits of Ziegler that Schiele completed in 1918: the other shows the sitter half-length in a three-quarter profile, dressed in a softly detailed blouse (fig. 2). Together, these works exemplify the subtlety and restraint of Schiele’s late portraiture, in which the expressive line becomes a vehicle for introspection rather than provocation.

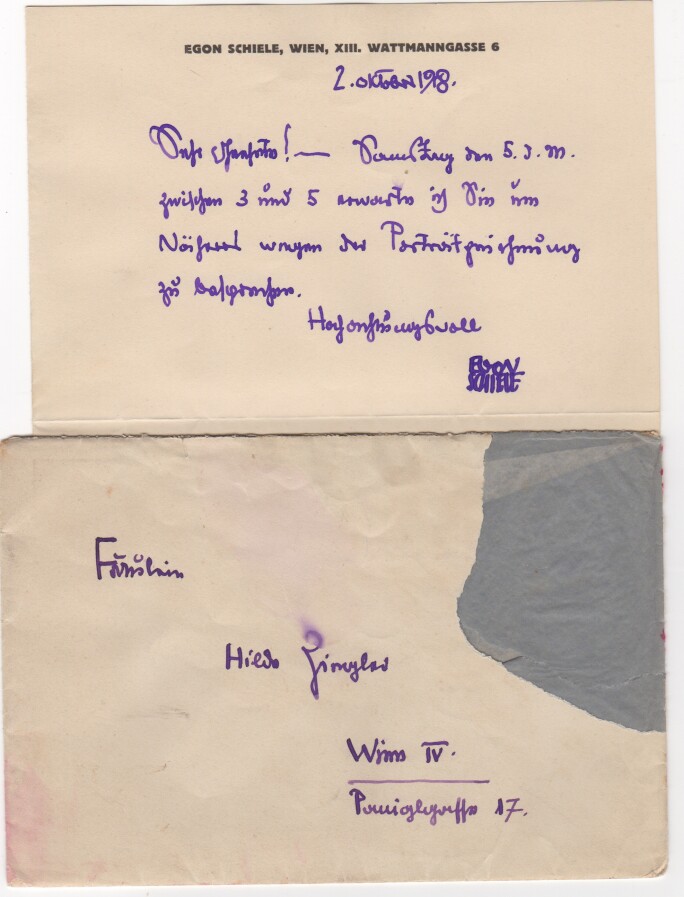

Ziegler was a student at Dr Eugenie Schwarzwald’s progressive gymnasium for girls in Vienna, an institution deeply rooted in the ideals of liberal education and artistic innovation. Schwarzwald, herself a pioneering feminist and cultural patron, often enlisted key cultural figures such as Oskar Kokoschka and Arnold Schönberg to teach at her school. As Ziegler’s daughter recalls in relation to this, “So it was not surprising that her schoolmates came up with the idea of asking Egon Schiele for a drawing for their school newspaper. The only question was how to go about it. According to my mother, the classmates' response was: ‘Hilde, you go, you're the bravest!’ And that was true – my mother was characterised by courage and initiative; that’s how I experienced her as well. Whatever she set her mind to, she pursued until she achieved it. So she went to Schiele and made her request, to which Schiele replied: ‘Yes, but only on the condition that you let me draw you.’ My mother responded quickly: ‘But only the head’. On 2 October 1918, Schiele invited her by letter to come to his studio on 5 October. On 19 October, two drawings were created as a result” (correspondence with Sotheby’s, May 2025) (fig. 3).

In Porträtstudie (Mädchenkopf) - Hilde Ziegler, Schiele employs spare yet precise lines to define the sitter’s angular features, placing her slightly off-centre, suspended in a blank field of paper. Her thick, dark hair, rendered as a tangle of expressive curls and shadows, contrasts with the pale clarity of her face, where a steady, unflinching gaze meets the viewer. The portrait resists sentimentality; there is a psychological ambivalence in Ziegler’s expression that underscores Schiele’s extraordinary ability to probe beneath the surface. By 1918, he was in full command of his technique, and this drawing exemplifies the clarity and confidence of his late style. The artist who once favoured distortion and emotional excess now approached portraiture with calm, incisive exactitude. The impact of this drawing lies in the tension between intensity and restraint: a vivid, quietly revolutionary presence conjured not through embellishment, but through the assured minimalism of Schiele’s line.

“He had always been a demon draftsman [...] and his line, by 1917, had acquired an unprecedented degree of precision [...] Schiele's drawing technique – the armature upon which all his painted forms rested – had acquired an almost classical purity [...] Schiele's hand had never been surer, more capable of grasping, in a single breath-taking sweep, the complete contour of a figure.”

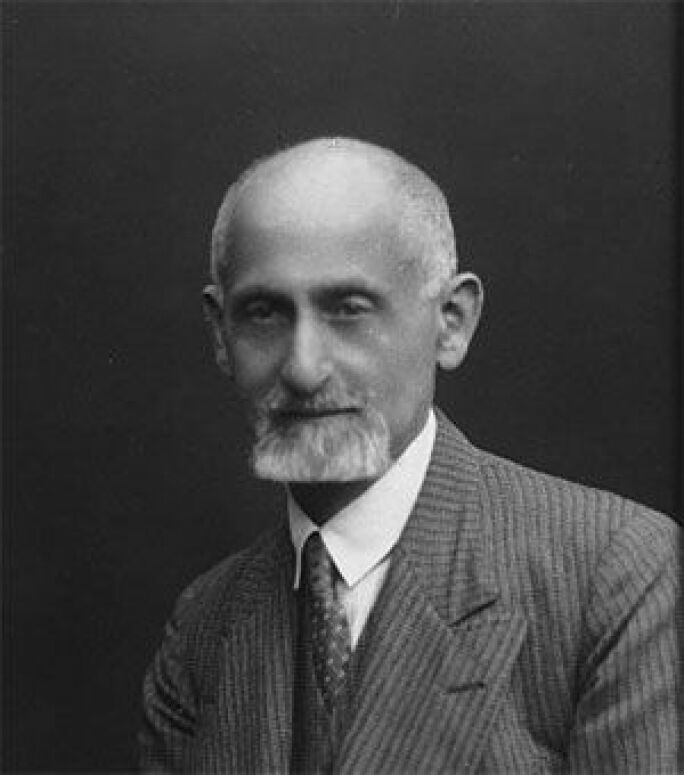

The significance of Porträtstudie (Mädchenkopf) - Hilde Ziegler is further distinguished by its provenance. Less than two weeks after completing the present work, Egon Schiele tragically passed away from the Spanish flu. Following his death, his brother-in-law and fellow artist, Anton Peschka, became involved in selling artworks from the artist's estate. Through the letters remaining in the Ziegler family, it transpires that Hilde reached out to Peschka asking to have her portraits. In the flurry of artworks, Peschka eventually managed to locate one of her portraits (fig. 1, sold at Sotheby’s in 2016). The present work, however, did not pass onto Hilde Ziegler at the time and instead made its way into the collection of Dr Heinrich Rieger. Hilde would have likely become aware of it following the publication in 1920 of a portfolio of Schiele’s works from Rieger’s collection by Ed. Strache, of which, as her daughter recalls, she owned a copy.

Dr Rieger was not only Egon Schiele’s dentist, but also one of his foremost collectors during the artist’s lifetime. Thirteen paintings are known to have been in his collection at one point, and his collection of Schiele works on paper surpassed a hundred.

Rieger’s discerning eye and active lending of his collection to exhibitions throughout Europe helped secure the legacy of Schiele and his contemporaries. An incredible group of 120 works from the Rieger collection were shown at the famous memorial exhibition for Egon Schiele in 1928, ten years after the artist’s death. In 1935 the Vienna Künstlerhaus even dedicated a whole show to Heinrich Rieger and Alfred Spitzer, another passionate collector of Schiele’s œuvre. Unfortunately, only a limited number of these works can be identified today. However, we do have certainty regarding the present work as it was included in the 1920 Ed. Strache portfolio.

The collection’s fate was marred by history. With Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany, Heinrich Rieger was persecuted for being Jewish. He was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942, where he was murdered. The present work is one of the rare restituted pieces from Rieger’s once vast holdings, with Sotheby’s having successfully assisted in the restitution and subsequent sale of several works by Schiele from Dr Rieger’s historic collection in the recent years.