"When we are hungry for soup, don't we seek out the culturally sanctioned brand name (Campbell's) and then select the flavor according to our taste? When we want a sweet, don't we reach for the trademark Life Savers and then select the taste we prefer by its color? And when a guy wants a girl, doesn't he seek out a version of Marilyn who suits his own emotional taste and décor? If this is so, how is our taste in high art any different? Is the process really that much more refined?"

More that any other artistic movement of the twentieth century, Pop Art was intertwined with its period of production, and in his Ads series Warhol confronts more directly than ever the consumerism that defined the capitalist culture of his era. Taking on brands such as Chanel, Mackintosh, Paramount and Mobilgas, Warhol reproduced logos and advertisements, elevating these images to the realm high art and in doing so exposing the artistry and power of the carefully crafted symbols themselves. Does the old time-y logo of Mobilgas, pictured as if a metal sign swinging in the wind off the side of a High Street, not conjure notions of tradition, familiarity and friendliness for the multi-national oil drilling company? Similarly, are we not seduced by the luster of Chanel’s iconic No. 5, luminous in its glass vial, justifying its expense by its very appearance? In the case of Lifesavers, the effect is more humorous. To lick an advertisement is one thing, but to lick a painting, let alone a painting by Andy Warhol, who by this time was as much a known brand as the companies whoso advertisements he coopted in Ads, is sheer lunacy. Further undermining the function of the image, isolating the signifier and by doing so altering the signified, Lifesavers epitomizes the subversive nature of Warhol’s practice, at a time in American history where advertising was king.

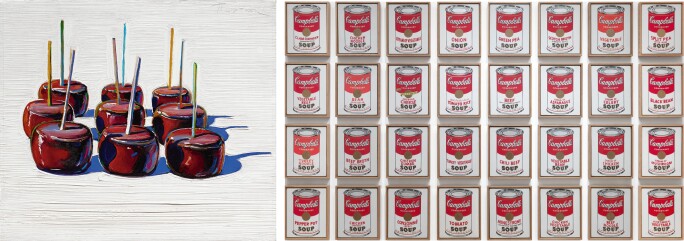

Right: Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Image: © Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence. Artwork: © 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London.

The present work is further distinguished by its vibrant, candy-colored decadence, itself a symbol of the succulent temptation of pervasive consumerism. The tempting rows of layered circular sweets printed in an array of pastels and vibrant tones ask to viewer to pick his favorite and lick it. As Dave Hickey describes: "When we are hungry for soup, don't we seek out the culturally sanctioned brand name (Campbell's) and then select the flavor according to our taste? When we want a sweet, don't we reach for the trademark Life Savers and then select the taste we prefer by its color? And when a guy wants a girl, doesn't he seek out a version of Marilyn who suits his own emotional taste and décor?” (Dave Hickey, "Introduction: Andy Warhol and the Dreams that Stuff is Made of," in: Andy Warhol "Giant" Size, New York 2006, p. 12)

As Donna De Salvo, Senior Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, put it, Warhol’s Ads exude “slick and perfect surfaces” and “candy-coated renderings” of iconic American imagery. (Donna De Salvo in: Freyda Feldman and Jörg Schellmann, Andy Warhol Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné 1962-1987, New York 2003, p. 31) These works beatify the promise of materialistic bliss and lie at the intersection of consumerism and art that so fascinated Warhol. Having worked as a commercial illustrator in the late 1950s before his career as an artist took off, Warhol was no stranger to the power and seductive capacity of images. In the present work he isolates the image and in doing so renders it impotent, making the viewer aware of the dominion of carefully designed advertising over the common man.