Dating to 1877-79, Le Pont de Sèvres en fin de journée, au fond l’église de Saint-Cloud depicts the view of the bridge at Sevrès with the spire of the Saint-Clodoald church at Saint-Cloud visible in the distance. Sevrès, a Parisian suburb about three kilometers southwest of the Bois de Boulogne renowned for its Royal porcelain factory, became Sisley’s home from the summer of 1877 until early 1880, prior to the artist’s move to a more rural town of Moret-sur-Loing where he would settle for the rest of his life.

The late 1870s were marked by financial difficulties for Sisley, the artist confessing in one of his letters to journalist Théodore Duret from this time: “I am tired of languishing as I have for so long” (artist quoted in Richard Shone, Sisley, London, 1992, p. 117). Yet, it was also a period that present-day scholars distinguish as one of the most creative in Sisley’s career, Christopher Lloyd remarking that “During the years when Sisley lived in Marly-le-Roi and Sèvres, he painted some of the finest pictures in his œuvre” (Exh. Cat., London, The Royal Academy of Arts; Paris, Musée d’Orsay and Baltimore, The Walters Art Gallery, Alfred Sisley, 1992, p. 149).

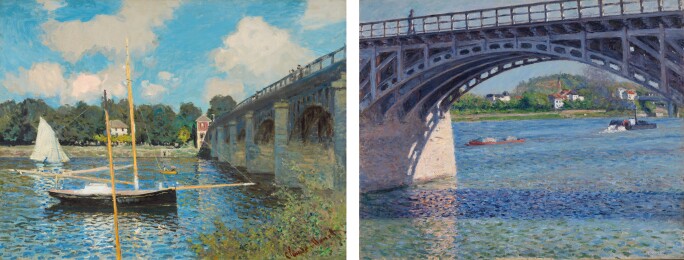

In the present work, Sisley adopts a compositional device that both him and his fellow Impressionists regularly employed to great effect over the course of the 1870s and beyond – that of a bridge extending across a river to a town visible on the opposite bank. Like fellow artists Monet and Caillebotte, Sisley often captured the gradual industrialisation of the historically sleepy suburban areas close to Paris (figs. 2 and 3).

Right: Fig. 3, Gustave Caillebotte, The Argenteuil Bridge and the Seine, circa 1883, oil on canvas, Museum Barberini, Potsdam

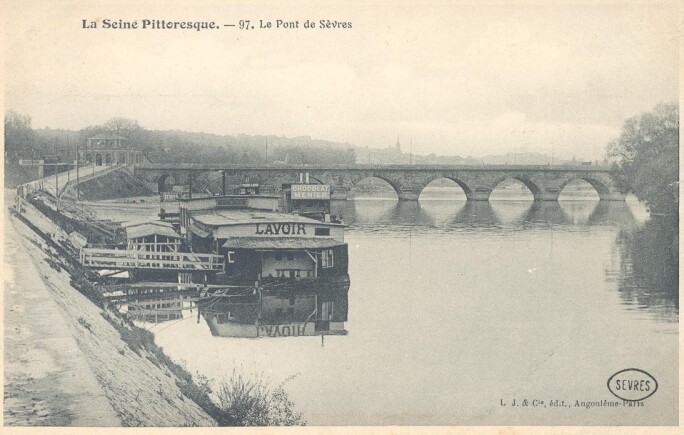

Sisley’s landscapes of the 1870s and 1880s, including the present work, almost always feature elements of man-made activity. Here, the bridge and the barges moored in front of it appear to blend harmoniously with the river and the surrounding grassy banks, reflecting Lloyd’s comment that Sisley does not appear to reject these changes to the traditional French landscape, but rather seems “to be accepting modernity as part of an evolving historical process” (ibid.).

However, at the heart of Sisley’s quest remains the capturing of the fleeting effects of changing weather and time on the surrounding landscape. In Le Pont de Sèvres en fin de journée, au fond l’église de Saint-Cloud, the artist renders, with superb sensibility, the ephemerality of the moment towards the end of the day just before sunset, with the bridge and the river’s right bank still basking in the evening sun’s glow, and the left bank and the foreground already covered in shade, the entire scene about to become enveloped in the evening’s encroaching darkness.

The present work is likewise distinguished for its intricate and complex brushwork, reflecting the changes Sisley’s practice underwent during this period. Lloyd remarked that in the works post-1876 “…a greater variety enters Sisley’s technique. The short soft-edged square brushstrokes of earlier years that resulted in an even surface on the canvas were replaced by heavily-worked, more intricate textures comprising a large range of brushstrokes. […] Concomitant with these richly textured surfaces was a greater sophistication in the application of color. [..] now the greater intensity and wider range of color, as in the work of Monet and Renoir, matched the more agitated character of the brushwork” (ibid., p. 151).

Having historically formed part of Durand-Ruel’s collection and featured in two important early exhibitions dedicated to Sisley’s œuvre organised by Durand-Ruel in Paris in 1902 and 1910, Le Pont de Sèvres en fin de journée, au fond l’église de Saint-Cloud comes to auction for the first time in twenty-five years, having since then belonged to a distinguished American collection.