“Let us image, a landscape whose combined vastness and definitiveness—whose united beauty, magnificence, and strangeness, shall convey the idea of care, or culture, or superintendence… a nature which is not God, but which still is nature in the sense of the handiwork of the angels that hover between Man and God.”

With Le Domaine d’Arnheim, it is Magritte who hovers in that realm of superintendence between man and God, the artist as designer, the architect of dreams and re-creator of realities. As Alex Danchev writes, “René Magritte is the single most significant purveyor of images to the modern world… Contemporary life is replete with Magritte and his sensibilities. His paintings are legends.” Of the hundreds of works completed in the artist’s lifetime, it is “Le Domaine d’Arnheim: a shattered window; the shards of glass showing the view outside,” which the biographer mentions alongside L’Empire des lumières, La Trahison des images, and La Durée poignardée as the most iconic works of the modern master’s career (Alex Danchev, Magritte, A Life, New York, 2020, p. xxvii).

Borne from the literary mind of Edgar Allan Poe—a favorite author of the artist’s—the subject of Magritte’s Le Domaine d’Arnheim takes as a point of departure the eponymous short story from 1850. In Poe’s tale, the first-person narrator tells of his friend Ellison, a wealthy aesthete rendered even wealthier by a windfall inheritance, and his “unceasing pursuit.” Ellison spends years seeking “the richest, the truest, and most natural, if not altogether the most extensive province” of all that may be poetic in sentiment, eventually landing on the pastime of “landscape-gardening” as the pinnacle field in which man’s intervention may perfect the natural world (Edgar Allan Poe, “The Domain of Arnheim,” 1847, accessed online).

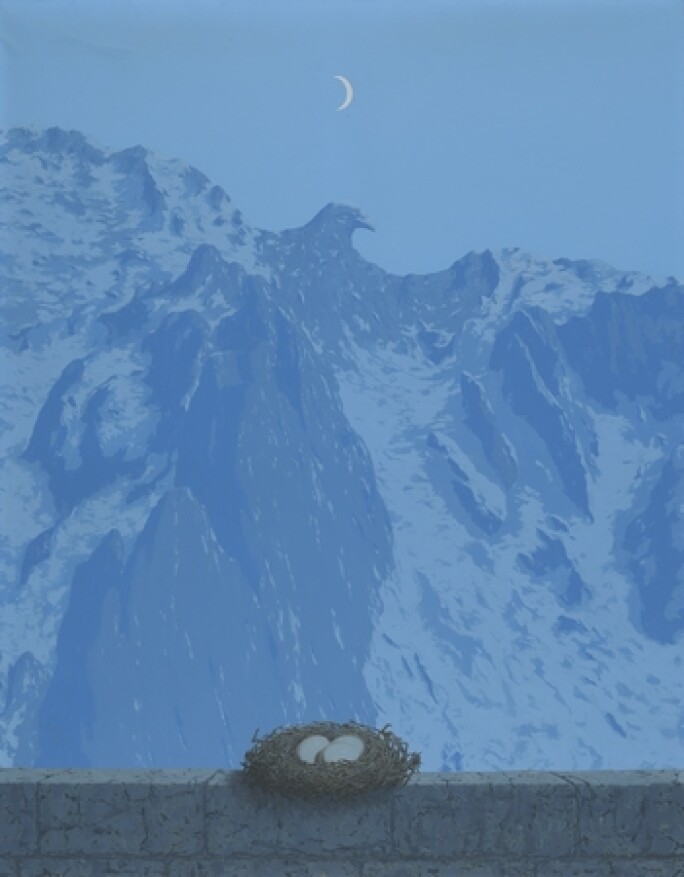

Painted in 1949, Magritte’s Le Domaine d’Arnheim explores similar entanglements of the organic and the contrived. The sculpted mountain range at the aft of the composition implies the intervention of man, while the subsequent thresholds of the window and the interior at the fore confirm it. At once, nature and artifice are separated as well as linked by the broken panes of glass which duplicate the vast landscape beyond.

Such Poe-inspired explorations of the manmade and natural worlds had already manifested themselves in Magritte’s work by the previous decade. In 1938, the artist executed the first of three oil compositions by the same title. Smaller in scale and rendered in a grisaille-like palette, this early work was also precipitated by the artist’s dream-like vision of an egg in a cage, the correlation between which he later termed “elective affinities.” Magritte’s search for the conceptual linkage between such disparate yet related images would underline much of his output in subsequent years as he sought answers to the “problem” objects which occupied his headspace. In the 1938 picture, the foreground is dominated by an Old Master-esque still life of two eggs, behind which lies a soaring Romantic landscape topped with an eagle-headed peak; absent is the presence of man. Still as the scene is, the untouched reverence of the landscape is belied by the engineered windowsill and carved mountaintop.

As critic Robert Hughes expounds, “[Magritte’s] work was more about situation than narrative [but] his titles were important to him, and they are never neutral. They were, so to speak, pasted on the image like another collage element, infecting its meaning without explaining it. They reflected his browsing in high and popular culture... The Domain of Arnheim... is the title of Poe’s 1846 tale about a super-rich American landscape connoisseur who creates a Xanadu for himself. ‘Let us imagine,’ says Poe’s hero, ‘a landscape whose combined vastness and definitiveness—whose united beauty, magnificence and strangeness shall convey the idea of care, or culture… on the part of beings superior, yet akin to humanity…’ Yes, one can well imagine Magritte liking that. His work too sets up a parallel world, extremely strange and yet familiar, ruled by an absolutist imagination” (Robert Hughes, “The Poker-Faced Enchanter,” Time, 24 June 2001).

The uncanny juxtaposition between nature and artifice present in the 1938 composition is further enhanced in the present work, executed a decade later. Though he gave it the same name, Magritte radically shifted the design and concept in the 1949 variation of Le Domaine d’Arnheim. Here, the artist has removed the objects of affinity—namely the eggs—opting instead for increased proximal separation between the subject and the viewer with the addition of successive layers of curtains, walls, windows and glass. Mitigating the distance in the scene is the curious repetition of the mountainous view in the shattered panes of glass at the fore. Propped up like characters of their own, these shards recapitulate the eagle-headed peak and craggy formations of the background within the interior.

By removing the eggs from the present composition, Magritte shifts the emphasis onto the mountain and the design of the eagle’s head, which itself derives from the German etymology of ‘Arnheim,’ meaning ‘home of the eagle.’ Characteristic of the Surrealist subversion of words and images, Magritte here addresses the inherent dichotomy between nature and artifice, sign and signifier. As Magritte wrote to Edward James upon the creation of the 1938 picture: “Penrose has managed to use images of objects to represent colours!... I am working on a picture on the basis of these findings. It is ‘The Domain of Arnheim’ in memory of the story by Poe, a man who, in my view, can give rise to thoughts such as the following: we move mountains so that the sun appears according to a specific wish” (René Magritte quoted in David Sylvester, ed., René Magritte, Catalogue Raisonné, vol. II, London, 1993, p. 262).

The “problem of the mountain” appears to have captured Magritte’s attention by the 1930s, with a nascent version of his eagle-head peak appearing in his paintings as early as 1926 in Les Epaves de l'ombre, later evolving to a full-fledged bird-mountain by 1936 in his versions of Le Précurseur. The vantage of the angular mountain peaks may well have derived from a travel brochure in his possession at the time, one that featured a panorama of the Alps. Decades later, in 1962, Magritte would complete the third and final composition titled Le Domaine d’Arnheim, returning once again to the dichotomy of eggs set before an eagle-headed mountain as in the initial variation of 1938, this time in a cool array of blue hues.

Notable in the present work is another of Magritte’s most iconic motifs, that of the blue sky with cottony white clouds. Similarly, renowned works like L’Empire des lumières, Les Valeurs personnelles, Le Faux miroir and La Décalcomanie are instantly recognizable as among Magritte’s corpus due the primacy of the cumulous backdrop, which adds a disarming quality to such complex and logically confounding scenes.

The present work, with its enhanced juxtaposition between the interior and exterior realms and the shattered pane between the two, aligns perhaps most closely with a suite of three other paintings created between 1936 and 1964. Though each work is known by a different title, all four compositions are rendered in a vertical format with an arched window and curtains along the periphery and a shattered window reflecting a landscape in the broken shards. Of this suite of images, Le Domaine d’Arnheim is the only example to feature the mountain range in the background and the only one in which the landscape itself suggests human cultivation, here in the form of the eagle-head peak. Of the three other related works, two are in museum collections, with Magritte’s 1936 La Clef des champs held at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and the 1964 composition, Le Soir qui tombe, The Menil Collection in Houston.

Magritte’s Shattered Glass Compositions

The trope of the window or mirror as both a portal and a mode of mise-en-abîme can be traced through centuries of art history and was especially favored in Surrealist practices. Along with his Surrealist cohorts, Magritte employed the device of the window to challenge the nature of perception and reality. Like the missing casement in Dalí’s Figure à une fenêtre and the three-dimensional collage of Ernst's Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, the broken panes within Le Domaine d’Arnheim force the viewer to reckon with the fallacy of the image by emphasizing the unreal quality of the composition. Just as the verbiage in Magritte’s Le Trahison des images serves as a reminder that a symbol or image can only ever represent an object and not exist in its stead, so too does the shattered window.

Max Ernst, Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, 1924. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Another abiding element in Magritte’s oeuvre is the recurrent use of the curtain, employed in the present work to further accentuate the divide between interior and exterior settings and highlight the paradox of that which is concealed and revealed. As Jacques Meuris wrote about the motif in Magritte’s work: “From the very earliest canvases, once Magritte knew what he was doing, drapes were a repeated feature. They appear in both Blue Cinema (1925) and The Lost Jockey (1926), for example. One way of looking at them is as a technical device. They are usually shown with loops, giving them the appearance of open stage drapes, and they enable the artist, through a process of optical illusion, to locate the planes of his image within the pictorial space. Another way of looking at these drapes is as a way of suggesting the fallacious (misleading) nature of the painted picture in relation to what it actually represents. Hence the idea of the stage set, to which the drapes lend emphasis… However, the ‘meeting of drapes’ (Magritte’s phrase) adds a quality of obtrusive accumulation that causes the viewer to see quite different elements that sometimes assume the form of drapes and other drapes that present areas of sky or houses” (Jacques Meuris, Magritte, London, 1988, p. 169).

René Magritte, La Décalcomanie, 1966. Centre Pompidou, Paris © 2023 C. Herscovici, Brussels / ARS, New York

Abounding with a myriad of references to literary and popular cultural and arranged in dream-like sequences, Magritte’s works are ultimately endowed with their captivating power by the artist’s bravura handling. Le Domaine d’Arnheim arises from the brilliant period in Magritte’s career, by which time his technical skill and crisp draftsmanship had far surpassed that of his work in the 1930s and still the fertile concatenations of Surrealist thought flowed through his inventive imagery. By the late 1940s and early 50s, Magritte’s compositions took on a newfound clarity of both line and color, as seen in the bright sunlit hues of the landscapes and the detail in even the smallest shards of glass in the present work.

Both his conceptual and technical legacies would impact generations of painters to follow, from the ad-like word paintings of Ed Ruscha—once described as "a sort of cowboy Magritte gone Hollywood" by David Bourdon—to the mesmerizingly graphic oils of Gerhard Richter. In a testament to the importance of their dealer, it was Alexander Iolas—also Ruscha’s dealer at the time—who introduced the two artists during a visit to Venice in 1967.

With such a visual legacy and arresting body of work, Magritte’s artistic clout has only grown with passing decades, his oeuvre continuing to inspire successive generations. The conceptual gauntlet thrown in works like Le Domaine d’Arnheim grows ever more relevant in a world bombarded with infinitely mutable image and one in which man continues to alter the course of nature—just as Poe’s Ellison achieved.