A striking example of the artist’s early interest in visual conceit and pictorial illusion, Real Landscape depicts David Hockney’s conception of three different stages of painting a landscape: from a painting, to a tapestry of the painting, to a painting of the tapestry of the painting. Initially used in an August 1969 episode of BBC’s Canvas series featuring Hockney, “The Frescoes: Domenichino,” the present work was then gifted to one of the show’s producers, Bill Furness, whose collection it remained in for nearly three decades before being acquired by the present owner.

In the BBC episode, Hockney enthuses about examples of Domenichino’s frescoes in the National Gallery in London, paying particular attention to Apollo killing the Cyclops and its depiction of the Greek myth of Apollo killing two Cyclops, illustrated within a tapestry that is folded back in the bottom right-hand corner of the fresco to reveal a dwarf, a clever use of trompe l’oeil that blurs the “real” subject of the painting. Hockney, after visiting the National Gallery a few years earlier in 1963, remarked of Domenichino’s works that “They were paintings made to look like tapestries made from paintings, already a double level of reality. All of them had borders round and tassels hanging at the bottom and perhaps an inch of floor showing, making the illusionistic depth of the picture one inch.” (David Hockney, David Hockney by David Hockney, New York 1976, p. 90). Hockney's interest in Domenichino's rendition of the tapestries and their borders immensely inspired the artist and would later serve as the basis for his own experimentation with the subject of the tapestry.

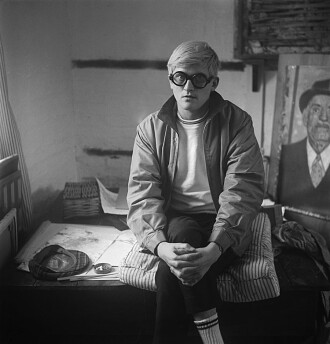

Right: David Hockney, Seated Woman Being Served Tea by Standing Companion, 1963. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In Real Landscape, the artist left notes in the lower margin outlining the ways that the landscape should be depicted across his three versions, paying particular attention to its borders and noting that the tapestry itself just has its loose fringe while "the picture must have an edge" in the painting of the tapestry. The third rendition of the landscape and the ostensible culmination of its stages features a small figure, seemingly Domenichino himself, hovering above the work with a brush in hand, another ploy of Hockney's to play on the theme of a picture within a picture. The drawing, a masterful summation of many of Hockney's most pressing interests, serves as a key vestige of the artist's explorations into the very nature of the painted surface through one of his earliest inspirations, a source that would inspire his work for decades to come.