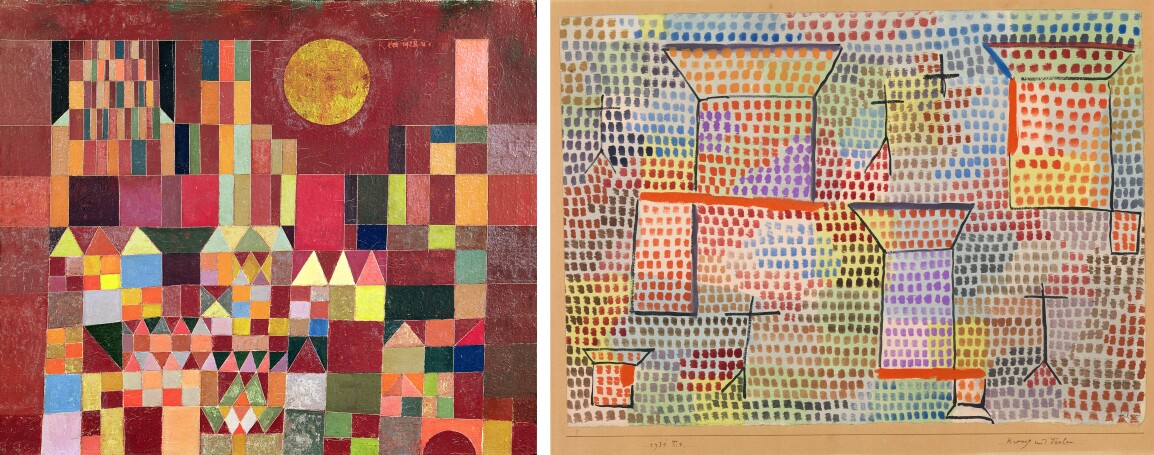

Painted in 1931, Reste einer Burg is a remarkable example of Klee’s characteristically playful treatment of the strict rules of compositional construction. The heightened chromatic relationships at work in this almost iridescent watercolor speak to Klee’s ability to strike a delicate balance between formalism and imagination. The resulting work, at once structural and dematerialized, intuitive and imaginative, speaks to a unique moment in Klee’s career—a moment in which he reconciled the influence of the Bauhaus ethos with his aspirations towards his own distinct artistic style.

Following the architect Walter Gropius's invitation to teach at the Bauhaus, Klee moved to Weimar, and the subsequent years, from 1921 to 1931, were to be the most innovative and productive of his career. Inspired by the Bauhaus belief in constructivist art, Klee's work became increasingly abstract and geometricized. “When I became a teacher,” Klee wrote, “I had to account explicitly for what I had been used to doing unconsciously” (the artist cited in Carola Giedion-Welcker, Paul Klee, New York, 1952, p. 50). In his post as the Formmeister, Klee was responsible for teaching courses on “Handling Methods of Form'' and on the fundamental mechanics of art. In his book, Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch, which documents the lectures he gave over his 10 year tenure at the school, Klee contends that “the truly essential can be identified and represented in ever-new variations and combinations by means of the basic elements of line, plane, and color” (ibid., p. 62). Regarding the line, Klee writes of its expressive potential and its capacity to communicate both spatial and psychological movement. The present composition oscillates between ascent and descent, allowing for the central structure, deconstructed as it might appear, to bear the potential of being whole again. The viewer can imagine the fragmented lines extending into the space between the blocks of color to form the castle that once stood where its remnants now appear. This notion, of collapsing the distance between past, present and future, was central to Klee’s oeuvre.

Architecture had been an important source of inspiration for the artist since the early days of his career and long served as a vehicle for his exploration into the relationship between the ephemeral and the physical. “Everywhere I see only architecture, linear rhythms, planar rhythms,” he wrote in his diary as early as 1902 (the artist quoted in Jürg Spiller ed., Paul Klee. Notebooks. The Thinking Eye, vol. I, London, 1961, p. 234). This sense of rhythm is beautifully rendered in the present work. While Klee based the composition on a vertical and horizontal grid, his careful grouping of color defies the constraints of that underlying organization, creating a sense of excited vibration that flows through the structure of the castle at the center. Klee’s rhythmic approach to architecture was markedly different from that of his contemporaries. Lyonel Feininger’s Der Dorfteich von Gelmeroda (1922, Städel Museum, Frankfurt) and Charles Demuth’s My Egypt (1927, Whitney Museum of American Art) each reflect a general fascination with the external, planar quality of the appearance of their subjects. But where there is tangible weight to the buildings Feininger and Demuth depict, Klee’s lines indicate structure without describing reality. He manages to maintain some suggestion of the realistic motif in which the scene is rooted while also achieving a complete dematerialization of the physical world.

Right: Paul Klee, Kreuze und Säulen (Crosses and Columns), 1931. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich / Sybille Forster / Art Resource, NY. Art © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

As Carola Giedion-Welcker explains, for Klee, “the theory of art is the outgrowth of the practice, not the other way around” (Giedion-Welcker, ibid., p. 50) Experimentation was integral to his process of understanding the mechanics of art and the basis on which his ideations were formulated. His Pointillist phase, of which the present work is an exquisite example, was one such period of experimentation. During this time, from 1930 to 1932, Klee explored what it meant to reconceptualize a scene in terms of color structure. With works like the present, Klee had discovered a new visual language, one whose letters, the delicate blocks of color, could be arranged into infinite sentences. In his own words, he managed “to achieve the greatest possible movement with the least possible means” (quoted in Jürg Spiller (ed.), Paul Klee. Notebooks. The Thinking Eye, London, 1961, vol. I, p. 234). In these mosaic-like compositions, Klee offers a view of the world that is at once kaleidoscopic and vigorously structured, as if seen through the fog of a dream.

Klee’s time at the Bauhaus in many ways freed him from the notion that to work with the mechanics of art meant to work within the laws of the physical world. Klee came to understand the tools of representation as being truly separate from that which was being represented. As he wrote in a Bauhaus prospectus, “construction is not totality [for] intuition still remains an important element” (the artist quoted in Exh. Cat., Madrid, Fundación Juan March, Paul Klee: Bauhaus Master, 2013, p. 84). The present work is a wonderful example of Klee’s ability to strike a balance between the two— between “construction” and “intuition.” Central is an undeniable sense of playfulness—one which cuts through the historicism of the subject matter and the formula of the composition.

Between 1929 and 1931, within the first two years of the Museum of Modern Art’s opening, Alfred H. Barr, the museum’s legendary director at the time, held two solo exhibitions of Klee’s works, introducing his idiosyncratic style to the American public. While his works proved too radical for contemporary critics, Klee’s oeuvre excited something untapped in its audience of American artists. Coupled with his writings, whose English editions were concurrently circulated, Klee’s works offered a theoretical underpinning for the wave of abstraction beginning to take root in New York. Klee did for these American artists what he did for his students back at the Bauhaus: he gave them a framework, a theory on composition, structure and form, which they could apply to their own devices.