“To paint is always to start at the beginning again, yet being unable to avoid familiar arguments about what you see yourself painting. The canvas you are working on modifies all previous ones in an unending baffling chain which never seems to finish. For me the most relevant question and perhaps the only one is ‘When are you finished?’ When do you stop? Or rather why stop at all?”

In 1948 at the age of 35 and already a celebrated artist renowned for large-scale figurative murals, Philip Guston dramatically immersed himself in an entirely new language of abstract painting with his radical work Review (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). The legendary corpus he completed over the next sixteen years, up until Portrait II of 1965 (The Art Institute of Chicago), positioned him in the foremost rank of the preeminent art movement of the twentieth century, Abstract Expressionism. The first half of the 1950s saw a gradual evolution of his tastefully nuanced, so-called "abstract impressionism," almost entirely comprised of subtly modulated monochromes in pinks and reds. However, in 1956 he executed the breakthrough Dial (The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), an intense structure of closely interlocking forms forged in ever bolder color and sheer black, all achieved by his working so closely to the canvas that he could abandon notions of space, depth and formal associations entirely. His paintings of the next four years, through to Painter I, II and III (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.), represent the pinnacle of his abstract practice. During this time he created just twenty-nine major surviving oils on canvas that measure greater than sixty inches. The masterpiece Nile of 1958 stands at the heart of this esteemed period, and relatively quantifiable analysis determines it among the top ten abstract paintings from this historic moment. Of those, Nile is one of only three of these very top canvases remaining in private hands. In sum, in each critical criteria of art historical importance; artistic quality; empirical rarity and commercial appeal, Nile is a truly extraordinary masterwork.

Each ridge and crest of Nile’s spectacularly viscous and variegated surface narrates its facture at the hand of Guston’s brush: the textured tactility a more instantly recognizable and powerful signature even than his name at the lower edge. This compelling and undeniable energy was achieved through a painstaking process of near devotional focus that typically lasted for weeks. In a 1966 interview, Guston remarked, “I want to show the canvas, it’s really just paint on canvas. It seemed to be part of the complication that I liked. If you’re making a drawing, you like to show some paper, uncovered. Or if you’re working with clay, if you’re modeling, you know how wonderful it is to see in a Rodin the head’s worked out and then a bunch of clay. It’s made of clay. I want to show that it’s really just paint too. Even though I’m trying to eliminate the paint, it’s still paint. I just enjoyed that feeling” (Exh. Cat., New York, The Jewish Museum, Philip Guston: Recent Paintings and Drawings, 1966, p. 69).

Layer upon layer of strokes were applied wet on wet atop of erasure, scraping and remodeling, to build up the sculpted surface. As Andrew Graham-Dixon noted, “Guston laid claim to a special immediacy and intimacy related to 'touch'… Guston had his pigments ground to create a particularly creamy consistency, and like thick butter applied to a hard surface, each stroke subtly squeezed out at its edges, creating a micro-sculptural effect” (Exh. Cat., Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Philip Guston Retrospective, 2003, p. 61).

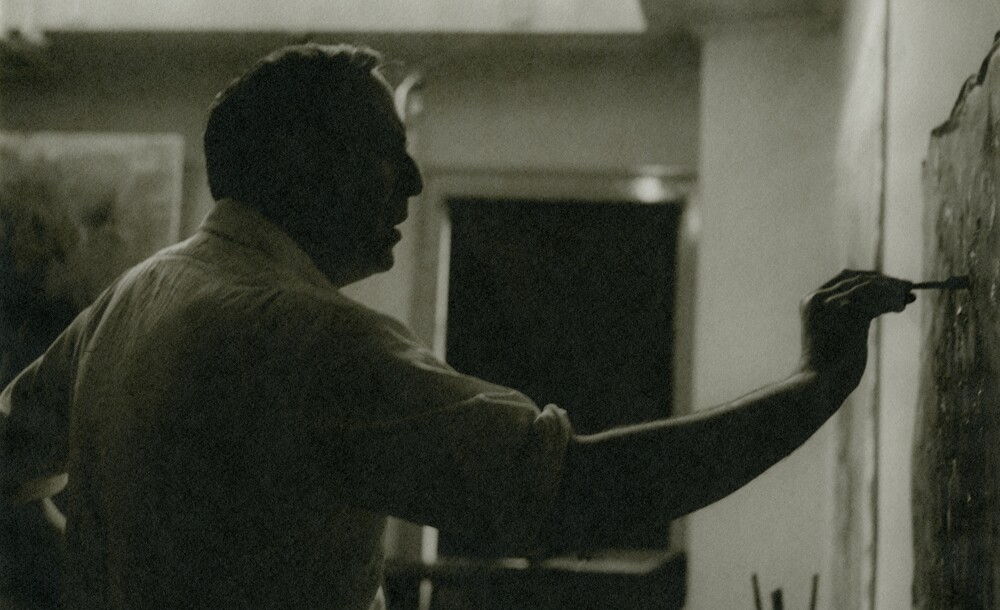

As Guston strove to resolve the opposing forces of a formalist structure and the pure, tactile material of paint itself, he developed an innovative working method that radically affected his output. While his contemporaries experimented with increasing the size of their canvases to create immersive experiences, most notably Pollock and Rothko, and others increased the size of their gestures, notably Kline and de Kooning, Guston increased his own proximity to the picture plane. As Michael Auping explained, “Guston was…engaged in the challenge of getting 'inside' the image, but his solution was unique. He didn’t see a need to radically increase the size of his paintings, but rather to change his own proximity and relation to them." As Guston would later describe it, “The desire for direct expression finally became so strong that even the interval necessary to reach back to the palette beside me became too long… I forced myself to paint the entire work without stepping back to look at it” (ibid., p. 40). Working so close as to lose all sense of space and depth, close enough for the paint splatters to get in his eyes, Guston forged a different type of painterly intensity, which reaches its apogee in Nile.

Guston’s Abstract Masterpieces in Prominent Collections

As is archetypal of Guston’s practice during the height of his abstract period, the title of Nile is both instantly evocative and enduringly elusive in equal measure. This is, of course, the inevitable outcome of attaching a clearly defined semantic label to a painting that is singularly intent on dismantling associative content. This paradox is not unique to Guston but in fact central to the evolving attitudes of the great Abstract Expressionists to the titles of their work throughout the 1940s and 50s. Indeed, this trend provides an important and often overlooked perspective on the shifting allegiance from the memory of figuration towards the arena of pure abstraction. As the new art form became increasingly unadulterated by semiotic referents, the role of textual designation was also reimagined. Hence the creation of titles by each of Pollock, Rothko and de Kooning variously graduated from elegantly poetic maxims that were often evocative of the legacy of European Surrealism, towards the determinedly dissociative and unprepossessing nomenclature of simply "Painting" and "Untitled" (themselves a nod to European forbears such as Joan Miró).

RIGHT: Joan Mitchell, City Landscape, 1955. Art Institute of Chicago. Art © 2022 The Estate of Joan Mitchell.

Guston carried the intimate memories of a vast trove of art historical images learned not least from extensive travel and experience. He was a devoted student of the Italian Renaissance and was self-confessedly in awe of Giotto, Uccello and Piero della Francesca among so many others. He was a prolific and notably voracious reader constantly immersed in literature, a dedicated connoisseur of music and an avid filmgoer, frequently visiting the movie theaters of downtown Manhattan after a day’s work in the studio. For decades he was renowned for engaging in philosophical discussion and discourse for many hours at a time with the coterie of leading artists and intellectuals around him. He was, in short, a formidable polymath whose art flowed from a profound reservoir of diverse inspiration.

Hence it is no surprise that the titles for some of his paintings from this period were rooted in specific and often esoteric sources. For example, the name of Cythera of 1957 is specifically indebted to Watteau’s painting Embarkation for the Island of Cythera, 1717, while Mirror to S.K., 1960, refers to the philosopher Søren Kieregaard and his musings on the subject of the mirror. As Guston’s titles become more elusive, any direct link to an exclusive source necessarily becomes more tenuous. For instance, it has been claimed that the sole source for his work Painter’s City, 1956-57, was Léger’s The City, 1919, but to unyieldingly refute the possibility of any other influence on such a multifarious title is to partly deny its inherent poeticism and the broad availability of interpretation to the viewer.

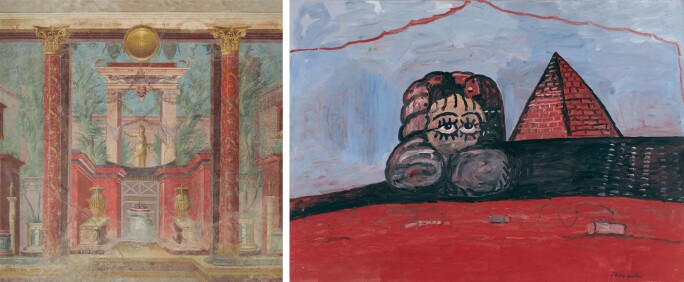

Within this context admitting possibilities of varying degrees of specificity, the title Nile admits a full pantheon of potential and illustrious sources. Within the canon of art history, the theme of the great Egyptian river was addressed for centuries principally through visual retellings of the story of Moses and the biblical legend of his discovery as a baby in a basket on the river Nile. One of the most spectacular of many superlative iterations of this subject is Sandro Botticelli’s 1481 fresco The Youth of Moses in the Sistine Chapel, which Guston would have had plenty of opportunity to study while he was a fellow at the American Academy in Rome in 1949. With respect to purely formal qualities of chromatic and tonal drama Nile can be seen to embody some of the spirit of the Renaissance masterwork, and it is not impossible that its memory was a catalyst for Guston’s title. Aside from the legion potential art historical influences, literary references may also have figured, from Shakespeare’s description of venomous snakes of the Nile (Cymbeline, Act 3, Scene 4) to Franz Kafka’s invocation of the river’s cleansing waters (Jackals and Arabs, 1917). Given Guston’s proclivity for the cinema it is also certainly admissible that the title was inspired by the role of the Nile in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 epic movie The Ten Commandments, in which the scene where Charlton Heston’s Moses turns the river to blood is one of its most enduringly memorable and again chromatically resonant with the painting.

RIGHT: Philip Guston, Nile, 1977. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco. Art © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Ultimately the title is precisely ambiguous; its inspiration both known only to Guston and also an open invitation to multivalent interpretation. While integral to the work, it is nonetheless subordinate to the primary visual experience of the painting and rather than being some opaque barrier, its enigma is essential part of an undefinable painting. Perhaps the most elegant epilogue is provided by a well-known ancient proverb, that itself describes Guston’s ambition to evade ready definition perfectly and may have been the ultimate inspiration: Facilius sit Nili caput invenire: "It would be easier to discover the source of the Nile."