B rimming with graphic vitality and formal sophistication, Surrealist Head II exemplifies Roy Lichtenstein’s masterful engagement with form at the apex of his sculptural practice. Executed in 1988, the work belongs to a powerful body of three-dimensional explorations that marked the artist’s late career and represents a striking synthesis of his decades-long investigation into style, perception, and art history. Characteristically bold and stylized, Surrealist Head II testifies to Lichtenstein’s enduring fascination with the female form—a subject that served as a recurring touchstone throughout his career and a vital conduit through which he refracted evolving dialogues around representation, desire, and archetype.

“It might be that Lichtenstein only appears to conform to this old model of sculpture, in part to complicate it, even to refashion it for his own ends... Yet in Lichtenstein there is no stable, a priori ground—it is often, quite literally, a void, an empty space—and meaning accrues through the image alone. Thus his evocation of relief is not a reversion to the old pictorialism of postmodernist art at all; it is, rather, a turn to the new pictorialism of postmodernist culture, through which Lichtenstein suggests that today even sculpture might be reformatted as an image, indeed that anything might be—a glass, a bowl, a light… Here ‘media’ has trumped ‘medium.’”

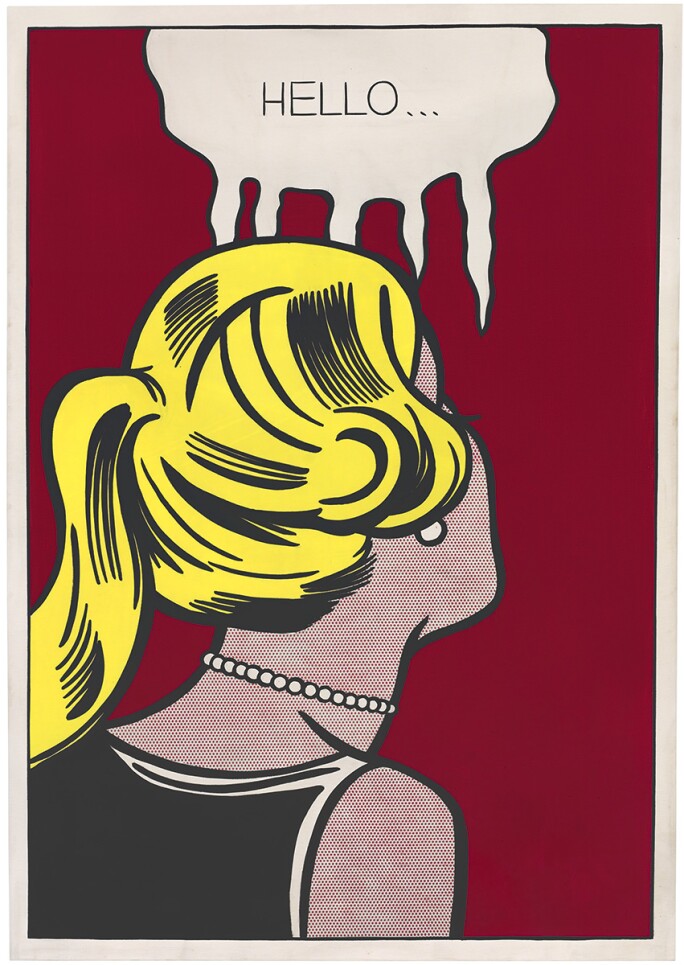

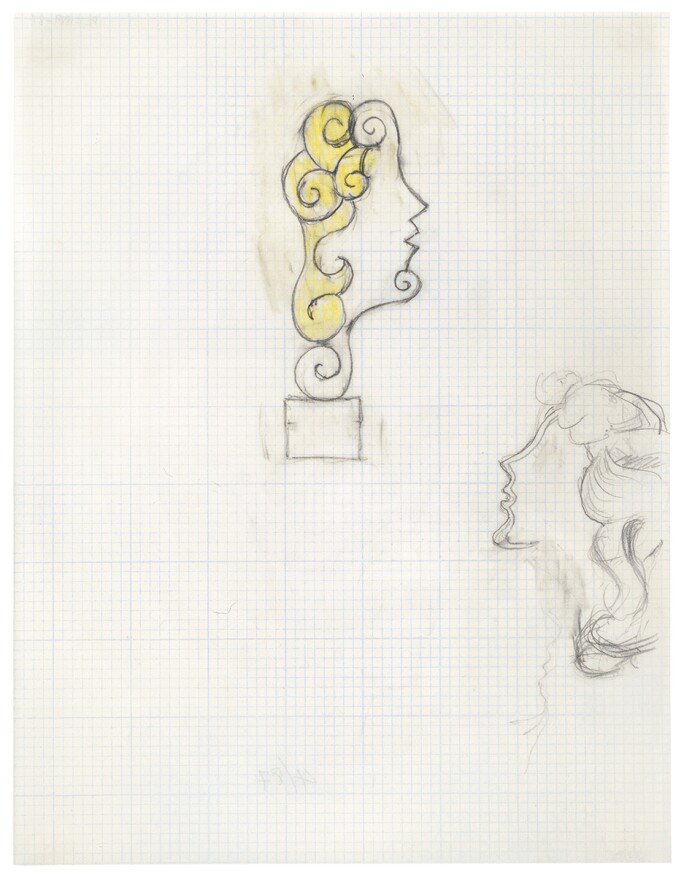

Reprising one of his most iconic motifs, the female face here is rendered with elegant, schematic efficiency: a crisp profile view composed entirely of fluid, exaggerated linework and sweeping spiral forms. Unlike the weeping heroines of his early 1960s comic-book paintings, this woman is abstracted to the point of ornament—her jaw sharply zigzagged, her lips a pointed triangle, her coiffure coiled into a sequence of rhythmic golden spirals. At once stylized and exuberant, the yellow silhouette of her hair pulses with energy, offset by the deep black patina of the bronze structure. The contrast evokes the illusion of a flat illustration, yet the physicality of the sculpture grounds it firmly in space.

What is most remarkable is the way in which Lichtenstein transforms the volume and mass of a traditional bust into a drawing in space. Surrealist Head II operates less as a three-dimensional object and more as a graphic cutout—its silhouette delineated with such clarity that the sculpture reads like a cartoon glyph extruded into the real world. This playful flatness is central to Lichtenstein’s practice, where the legibility and reproducibility of signs often take precedence over illusionistic depth. The flat yellow plane—painted onto the interior of the hair’s silhouette—becomes a vibrant foil to the black curvilinear armature, casting shadows that subtly animate the surface and recalling the artist’s lifelong fascination with the intersection of light, contour, and perception.

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Lichtenstein turned to bronze—traditionally the most venerated sculptural medium—to elevate his Pop idiom into a dialogue with classical and modernist tradition. But with Surrealist Head II, he subverts the gravitas of bronze by treating it like a drawn line—supple, looped, and cartoon-like. In doing so, he collapses distinctions between drawing and sculpture, between high and low, between timelessness and trend.

While Lichtenstein’s women of the 1960s mined the vernacular of pulp romance and mass media to interrogate the emotional shorthand of pop culture, his late female busts draw on a broader and deeper artistic heritage. With its sculptural contours and stylized elegance, Surrealist Head II echoes the influence of Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse, the classical repose of ancient Greek Kore statues, and the biomorphic eccentricity of Picasso’s surrealist heads. As the title suggests, the present work is part of a dialogue with Surrealism’s inventive approach to form and identity, evoking the genre’s tendency to fracture and recompose the human figure in ways that both reveal and conceal. Yet Lichtenstein’s take is resolutely postmodern: rather than delving into the subconscious, he filters the image through the mechanisms of style and semiotics, emphasizing the aesthetic conventions that shape our collective visual memory.

In this light, Surrealist Head II becomes not simply a depiction of a woman, but a meditation on how the idea of “woman” has been encoded, stylized, and repeated across time. Her flowing spirals suggest both stylized hair and abstract embellishment; her sharply edged profile evokes ancient coins, Deco brooches, or 1980s fashion illustrations. It is no coincidence that the entire structure is freestanding yet two-dimensional: Lichtenstein encourages the viewer to circle the piece only to return, again and again, to its frontal graphic punch. Indeed, the stylized femininity of Surrealist Head II can be read as both homage and critique—an acknowledgment of the historical role women have played as muses, allegories, and subjects of idealized beauty in art history. In this regard, Lichtenstein’s sculpture echoes the canon while interrogating its assumptions. His heads are not portraits, but emblems: representations of representation itself. Through their graphic clarity and symbolic reduction, these works examine how far iconic features—spiraling locks, geometric profiles, symmetrical silhouettes—can be pushed into abstraction without losing their effective charge.

As a sculpture that traverses eras, cultures, and stylistic boundaries, Surrealist Head II occupies a unique and compelling position within Lichtenstein’s oeuvre. It distills a lifetime of formal inquiry into a singular, commanding object—one that is at once deeply rooted in the past and unmistakably of its time. In its chromatic boldness, rhythmic contours, and conceptual clarity, Surrealist Head II exemplifies the enduring relevance of Lichtenstein’s practice and affirms his place as one of the most visionary artists of the 20th century.