Painted in 1907, Crucifixion with darkened sun dates from the very beginning of Schiele’s career and in many ways anticipates the key elements of his work over the next decade. The previous year, aged only sixteen, Schiele had moved from the town of Tulln to Vienna in order to study at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste. Whilst still a student there, he painted the present work, revealing his spiritual preoccupations from an early age. The work is one of only two oil paintings in Schiele’s career which depict the theme of the crucifixion but stands alone in its innovative approach to the subject. A few years later in 1912 he would paint Calvary (fig. 1), a landscape which shows the crosses at a distance; the present work on the other hand is a psychological exploration into the nature of humanity, with the three figures shown in close up from the side. Both works are radical reimaginings of this traditional imagery, but it is the synergy of the emotive and the decorative present in Crucifixion with darkened sun which makes this work one of the most interesting creations of Schiele’s opus.

In his early years, Schiele was greatly influenced by the art of Gustav Klimt, the leader of the Secessionist style, who was his friend and mentor from 1907. The Klimtian aesthetic was grounded in sinuous lines and decorative detail and it is possible to trace some of that influence in Crucifixion with darkened sun. Certainly the fluid lines which demarcate the hill, sea and sky and the ornamental depictions of Christ’s halo and the sun bear some resemblance to the older artist’s treatment of form. Schiele also employs the Klimtian square-canvas format which heightens its visual impact and creates a marked difference to traditional painting. This square format imparts two effects: firstly, the symmetrical shape contains the scene with a tighter efficiency, and secondly, the square increases the sense that these are paintings are for contemplation.

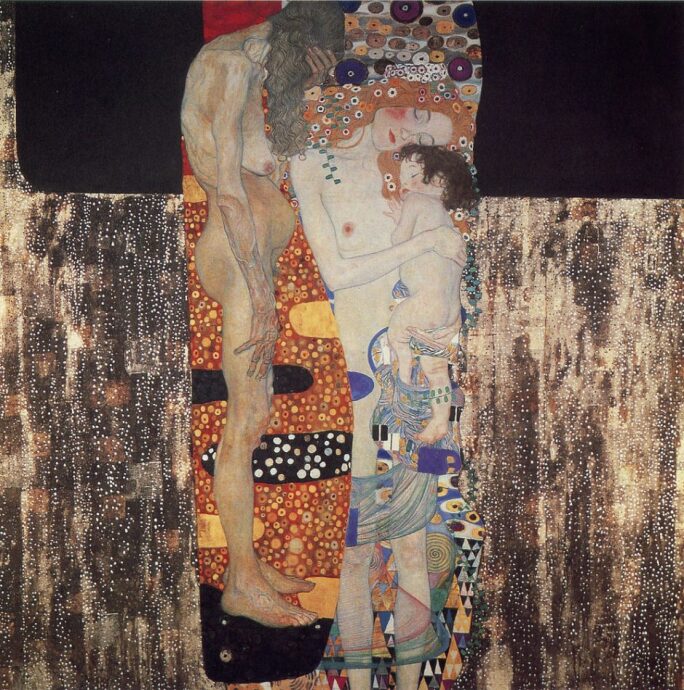

Crucifixion with darkened sun, however, crucially demonstrates how Schiele began to step out from the shadow of his mentor to forge his unique and celebrated style. Even Klimt’s more philosophical compositions – The Three Ages of Woman being a prime example (fig. 2) – are suffused with a decorative quality that softens and ameliorates the subject. Schiele, on the other hand developed a more direct and challenging pictorial language, transfiguring his own personal experiences into emphatic discourses upon the human condition. His childhood, which involved the death of family members but also the privileges of being an only son, had taught him to juggle conflicting emotions and responses, equipping him to tackle the emotionally complex subject of the crucifixion. As Jane Kallir writes: ‘The ease with which Schiele […] was able to transmute personal experience into a universally valid symbolic image is indicative of the manner in which a more wholesome integration with his environment had affected his work. Though many of his later allegories continued to hinge on self-portraiture, they no longer focused on Schiele’s role as an artist, but on the larger human predicament' (Jane Kallir, Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, New York, 1998, pp. 178-181).

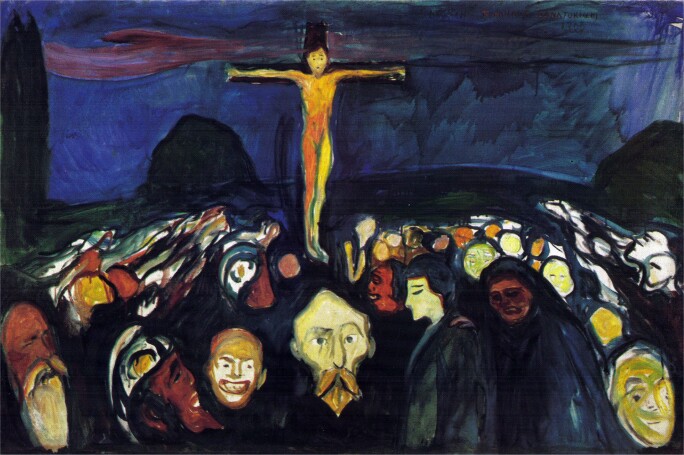

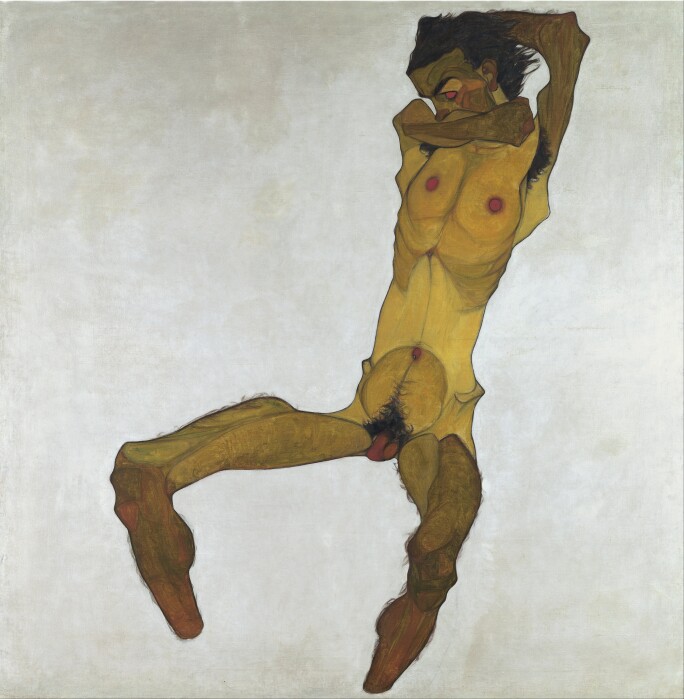

Schiele saw the human body as a physical materialisation of a mystical, unseen, but nonetheless dynamic life force and he pursued the extremes of human gesture in his art. Executed with angular and febrile lines, the three bodies in the present work hang from exhaustion and their rendering exemplifies Schiele’s virtuosity as a draughtsman, as well as anticipating his treatment of the human body later in his career. In painting the figure of Christ in this way, Schiele connects him to the later self-portraits (fig. 4) in which his own features become those of the everyman, symbolising universal human truths. It is possible that, even at this young age, the virtuosic artist was deliberately identifying himself with the figure of Christ, just as Edvard Munch had done in his treatment of the subject in 1900 (fig. 3). Interestingly, despite Schiele’s radical treatment of the subject – a powerful departure from traditional renderings of the Passion, the scene preserves some of the underlying meditative quality of these earlier altar scenes. The gradations of the purples, mauves and blues used for the sky and sea are applied in short, jagged brushstrokes, and the hint of orange around the darkening sun conjures a contemplative atmosphere. Looking upon the scene from a side-on perspective, the viewer’s eye is led to the body of Christ, whose shimmering halo symbolises the importance of his death. Crucifixion with darkened sun is melancholic but also hopeful: the colour palette instils a mystic glow, signifying the redemption of humanity, achieved only through Christ’s ultimate sacrifice.

In his quest for spiritual values Schiele used landscape as an allegory of human emotion. Kallir notes that the artist associated his beloved father with the countryside and his mother with the city (ibid, p. 106). In 1913, Schiele wrote to his friend and future brother-in-law Anton Peschka: ‘I believe in the immortality of beings…Why did I paint graves? And many similar pictures? Because the memory (of his father) continues to live intensely within me’ (quoted in Christian M Nebehay, Egon Schiele 1890-1918, Leben Briefe, Gedichte, Vienna, 1979, p. 264). This aspect of his work has been widely explored; as Kimberley A. Smith writes: ‘Schiele’s landscapes are repeatedly characterized as anthropomorphic visions that transform trees and towns into metaphors for the human figure and as melancholic elegies exhibiting a readily perceptible fascination with death. The landscapes are thus seen as functioning much like the self-portraits. Their anthropomorphic forms reiterate the anguished explorations of personal identity more famously executed in the artist’s images of the human body’ (Kimberly A. Smith, Between Ruin and Renewal: Egon Schiele’s Landscapes, New Haven, 2004, p. 139). In this, Schiele was not alone, indeed he was following in a tradition that went back to the German Romantics but which had found new expression in the work of post-impressionist artists like Van Gogh (fig. 5), whose work Schiele would almost certainly have been aware of through reproductions and would see for himself at the 1909 Vienna Kunstschau.

Crucifixion with darkened sun marks the beginning of Schiele’s evolving Expressionist idiom but also reflects the primary stimuli in his art which was his admiration for and friendship with Klimt. Schiele’s talent in rendering human form and expression through landscape gives the present composition an exceptional force and brings to the fore the complex themes of death and redemption.

One of the finest of Schiele’s early works, Crucifixion with darkened sun was formerly in the collection of Doctor Heinrich Rieger. A discerning collector and friend of the artist, Dr Reiger had a dental practice at 124 Mariahilferstrasse which both Schiele and his wife Edith attended - he would often accept artworks in exchange for his treatment. Through this practice and spending most of his income on works by young Viennese artists, Rieger assembled one of the best collections of avant-garde Austrian art in Vienna.