Visually arresting in its free-flowing dance between painting and sculpture, Take My Hand stands as a testament to the remarkable praxis of El Anatsui. Under his vision, discarded bottle caps and other objects, some of which sit in his studio for years before use, are repurposed and assembled into mosaics of inexplicable allure. The sculptural undulations and stunning luster of the present work invokes the fluidity of movement of draped textiles, whereas the rectangular, stripped passages evoke the aesthetics of West African textile making traditions. In subsequent works, Anatsui implemented the striped motifs into smaller works designed to hang flat, resulting in a more representational composition reminiscent of a painted impressionistic landscape. The present work encapsulates the best of these contrasting motifs, seamlessly shifting from multi-dimensional sculpture to a flat pictorial plane.

"Well, Take My Hand, its origin is from a song which was rendered by Aretha Franklin. “Precious lord, take my hand, lift me up…” I am someone who listens to spiritual gospel music, and a lot of the time I take my titles from this moving music."

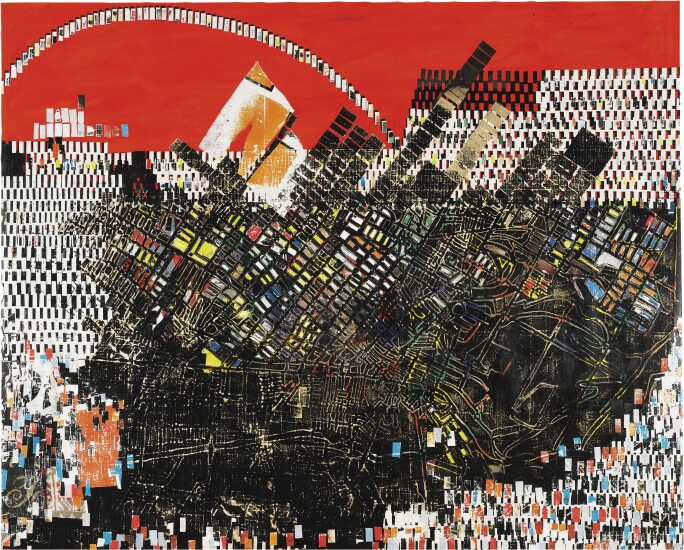

The bottle-cap works build upon the legacy of twentieth-century abstraction and amalgamate a plethora of cultural and art historical influences. Writer and critic Julian Lucas asserts of Anatsui’s early rise to fame, “In a highly fractionalized art world, Anatsui found universal acclaim. To formalists, he was an Abstract Expressionist who worked in aluminium refuse; to the postmodern and the post-colonially minded, a maverick interrogator of consumption and commerce; to Old Guard Africanists, a renewer of ancient craft traditions. To most, his work was simply beautiful, with transcendent aspirations rare in the self-reflexive context of contemporary art. As it turned out, the unfixed form wasn’t just a way of sculpting. It was the principle of a career that had opened itself to the world without sacrificing its integrity” (Julian Lucas, “How El Anatsui Broke the Seal on Contemporary Art”, The New Yorker, 11 January 2021 (online)). Anatsui's practice emphasises the boundary between our knowledge of the past and the reality of historical events, and his fluid sculptures often become a symbol of the colonial destruction of African cultures.

The Broad, Los Angeles

Image: © The Broad

Artwork: © Mark Bradford 2023

Anatsui’s iconic ‘metal cloths’ rose to prominence after a seminal travelling exhibition entitled Gawu (a word derived from Anatsui’s native language Ewe meaning ‘metal cloak’) which soon established the artist as a trailblazing and innovative voice in contemporary African art. Anatsui discovered the bottle caps and seals as artistic media in 1998, when walking in the outskirts of Nsukka, the Nigerian town where the artist lives and works. He found a bag of discarded loose caps on the roadside and kept them in his studio for two years before employing them in his sculptural work. The caps opened up a vast spectrum of possibilities, later imbuing in Anatsui’s sculpture a distinct flexibility and freedom, comprising a material that was simultaneously malleable, local, plentiful and inexpensive. Today, his choice of found materials is not limited to liquor bottle caps, but rather includes caps from a spectrum of consumer goods, including medicine, wine, olive oil, and bitters, as well as pieces of aluminium roofing strips, the latter of which give his compositions specific hues of blue, green and beige. Such materials introduce the textures, structure and flow of Anatsui’s local Nsukka cityscape: “I believe that artists are better off working with whatever their environment throws up. I think that’s what has been happening in Africa for a long time, in fact not only in Africa but in the whole world, except that maybe in the West they have developed these ‘professional’ materials. But I don’t think that working with such prescribed materials would be very interesting to me – industrially produced colours for painting. I believe that colour is inherent in everything and it’s possible to get colour from around you, and that you’re better off picking something which relates to your circumstances and your environment than going to buy a ready-made colour” (El Anatsui quoted in: Polly Savage, “El Anatsui: Contexts Textiles and Gin,” Moving Worlds: A Journal of Transcultural Writings, n.p.). Anatsui’s compositions thus transform simple, everyday materials integral to his local surroundings into striking, large-scale installations, thus elevating such discarded objects into the realm of fine art.

Image/Artwork: © El Anatsui

Anatsui’s tapestries spectacularly record and present the patterns of consumption and exchange which characterise the communities around his studio in Nigeria and Ghana. Anatsui’s ability to metamorphosise the status of objects from unwanted waste into objects of desire critically references the transformative capacity of perception. Through this process of recontextualization, Anatsui offers a poignant reflection on the interconnectedness of our world and the transformative power of art. The Ghanaian artist’s metallic mosaics are held in numerous museum collections including The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Broad, Los Angeles, The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi; and Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African in Cape town. Anatsui is a recipient of the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement of the 56th Venice Art Biennale, and has most recently been honoured with the Turbine Hall commission at Tate Modern.