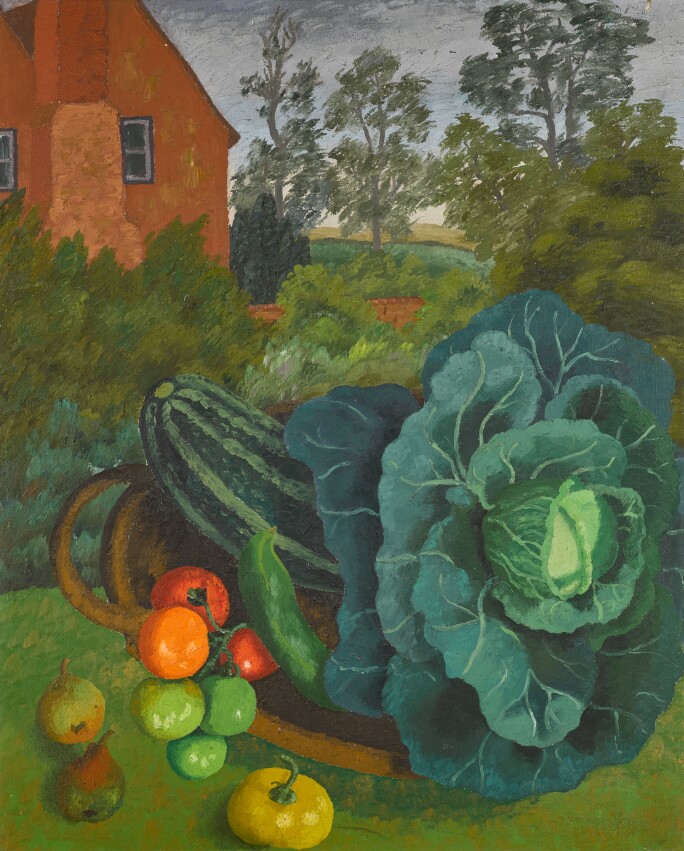

As a renowned horticulturist in his own right, it is impossible to separate Cedric Morris’ preoccupation with nature from his fleshy still lifes. Executed in 1968, Still Life in a Summer Garden is a beautifully verdant example of this life-long alliance and gloriously points to how intertwined the environment and painting were for Morris.

Set within the landscaped gardens of Benton End, the sixteenth century house Morris and his partner Arthur Lett-Haines made their home from 1940 onwards, the present work suffuses with the artist’s admiration for the Suffolk countryside whilst blending the pastoral subject of the traditional still-life with his informal Modernist style.

In 1937, Morris and Lett-Haines founded the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing. Following which, their home became a hub for many creatives, including, amongst others, a young Lucian Freud whose precocious talent was encouraged at the institution between 1939 and 1942.

‘He watched the natural world in much the same spirit that he observed the human comedy. A garden does not need to be thought of as a setting for events. It may be used as a form of theatre: for forty years the garden at Benton End on fine days was full of easels and students, conversations, al fresco lunches and parties.’

In the present work, Morris casts vegetables as the primary subjects or rather, guests of Benton End. Similarly to his earlier and equally theatrical painting Cabbages of 1953, Morris anthropomorphizes these objects by positioning them at the centre of the composition and enlarging them in an extravagant manner. Aided then by the artist’s meticulous eye for detail, each vegetable takes on a character of its own and appears to participate in the scene. One such line of dialogue is portrayed by the cabbage with its billowing leaves that rolls towards the lower left of the composition, almost as if its eye had been caught by something, or rather someone in that direction. Painting during a time when the art world had become increasingly dominated by the evolution style and technique, Morris’ theatrical presentation of vegetables reiterates his admiration for subject and the way it could be characterized through detail rather than being abstracted or deconstructed.

‘For Cedric the natural world was there to be sensuously celebrated.’

In addition to the characterization of these vegetables, Morris’ portrayal of the wider Suffolk countryside likewise points to this deep admiration for his surrounding environment. Establishing a sense of depth through subtle gradations of tone in the sky and rolling hills of the background, the landscape of Still Life in a Summer Garden likewise contributes to the overall character of the painting. Much like the design of a stage within a play, the texture of the fauna created by short brushstrokes and verdant blocks of colour helps to set the scene, elevate the position the primary subjects and in turn, furthermore evoke Morris’ extraordinary admiration for this little pocket of the Suffolk countryside. Joining together then his most personal modes of expression, painting and horticulture, Still Life in a Summer Garden not only offers an insight into the mind of the artist, but it also suggests how intertwined he believed these his beloved past-times to be.