The 1852 Harvard-Yale Trophy Oars

Presented by future President Franklin Pierce to the crew of Harvard’s Oneida on 3 August 1852.

The inaugural Harvard-Yale Regatta was not only the first athletic competition in this storied rivalry, but the very inception of American intercollegiate sports.

It all began when sixteen blades broke the water…

College athletics have come to be a cornerstone of the American cultural landscape and a central part of the college experience. The camaraderie and intense rivalries born out of the intercollegiate spirit shape not only the lives of students and alumni, but define the world of American sports—and American culture at large. These rivalries are legendary—whether it be Alabama-Auburn, Michigan-Ohio State, North Carolina-Duke, Cal-Stanford, or Army-Navy—and their annual matches are an essential platform for Americans to celebrate their regional, national, and college identities. Despite their now titanic stature, their beginnings were more modest, and can be traced back through one of the most storied rivalries in intercollegiate sports: that of Harvard and Yale.

The contest between Harvard and Yale is an institutional staple marked by competitions each year, including the annual contests on the gridiron—“The Game”—and the ice. But its origins lie in the very first intercollegiate athletic competition: “The Race.” First contested in 1852, the inaugural Harvard-Yale Regatta predates The Game by twenty-three years—as well as the very first college football game, between Rutgers and Princeton, by seventeen. The Race, now the longest-running intercollegiate athletic competition in the United States, remains one the most venerable contests between the two institutions. But The Race’s debut was not only the first sporting match between the two universities—it was the very inception of organized American intercollegiate sports.

In the early nineteenth century, student life at the two universities was still organized almost entirely around a routine schedule of church, lecture, and club life. The days began with early-morning chapel, followed by lectures and an afternoon meal—after which, time was largely free and unstructured for the students. Many would typically fill their hours with club activities—the Pierian Sodality and the Institute at Harvard, the Linonia and the Beethoven Club at Yale—and the earliest formations of national fraternities. Time was whiled away with debate and music, prayer and scholarly work, walking in the woods and college high jinks. Absent from their lives, however, was any organized physical exercise or sporting, beyond whatever casual games students might occupy themselves with.

In 1839 Charles Bristed, a Yale graduate who went on to Cambridge University to continue his academic career, was astonished to find that the Cambridge students undertook daily exercise, and noted:

“If instead of the thousand and one secret societies that fritter away their time and divide their attention from the regular studies of the college, the Yalensians would get up boat and cricket clubs, there might be some hope for them.”

And only three years later, as boating had grown popular in nearby Boston and New York, Bristed’s hope began to be realized. Throughout the early nineteenth century, boats and boating clubs began to dominate the harbors along the New England coast, and the first formal regatta in Boston would take place in 1842. As the landscape around the two universities began to develop—allowing students to venture further afield—students were able to leave the pastoral intellectual climate of campus and explore the surrounding areas. With the Charles River at Harvard and the New Haven Harbor just down the road from Yale, the landscape provided a ripe opportunity for college students to get in on this new sporting sensation.

In 1843 William Weeks, a junior at Yale, decided with his classmates that they ought to acquire a boat for rowing in the New Haven Harbor; on his way home to Long Island for spring break, Weeks stopped to procure what would become the Pioneer. After bringing the nineteen-foot-long boat back with him on a steam train, he and the seven other classmates—each having split the cost of the boat—founded Yale’s first boating club. Harvard’s first boat, originally named the Star, would arrive on campus only one year later. Thirteen Harvard juniors purchased the Star after it won a race nearby in Chelsea, where boating was flourishing, and renamed it the Oneida after bringing it back to the university.

Rowing boomed almost instantaneously on the two campuses following the arrival of the first boats, and throughout the remainder of the decade it became one of the most popular student pastimes. Nonetheless, rowing remained a relatively casual and recreational enterprise, until the first stirrings of The Race.

“In rowing, you're always striving for that perfect stroke, that repetition, each one being as good as the last.”

The First Race

In May of 1852, James Whiton, then a junior and the bow—the position closest to the bow of the boat, and part of the pair responsible for the boat's stability—of Yale’s brand-new Undine, took a leave of absence to return to his family’s home in Holderness, New Hampshire. His father was the director of a new train line running through the Winnipesaukee region, as part of the enterprising conductor James Elkins’ expansion of the Boston, Concord & Montreal Railroad. One day during Whiton’s sojourn, he rode on his father’s line, accompanied by Elkins, and the two began to talk. As the train traveled along the edge of Lake Winnipesaukee, the young oarsman commented on the suitability of the lake for a rowing race—also suggesting that viewers might be able to watch from an observation train. Elkins’ ears perked up. After hearing Whiton’s account of the popularity of rowing at the college, he declared: “If you will get up a regatta on the lake between Yale and Harvard, I will pay all the bills.”

It didn’t take long to get The Race together. After his crewmates agreed to the notion, Whiton took the proposal to Joseph M. Brown—the captain and coxswain of the Oneida at Harvard, who had previously been a classmate of Whiton’s at Boston Latin. After some deliberation, they agreed to compete. They set the date as 3 August, following Yale’s commencement, “to test the superiority of the oarsmen of the two colleges.”

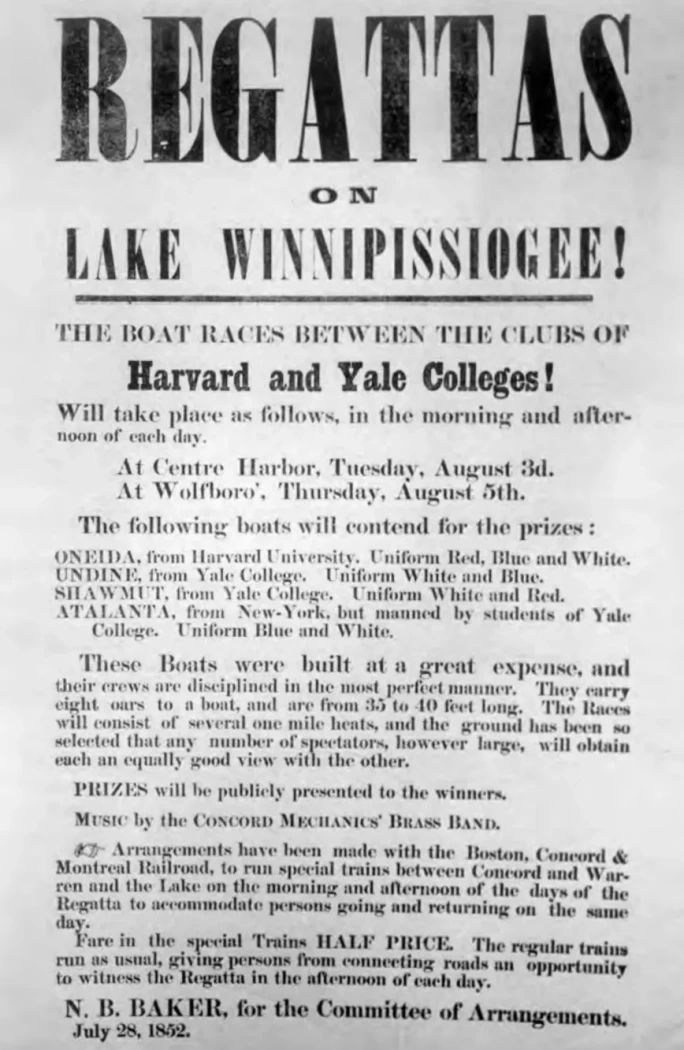

The industrious Elkins, thinking that the event could draw massive ridership to his new train lines, plastered the cities and towns along his railways with fliers extolling the fineness of the boats and their crews. He announced special excursion trains running along the Boston, Concord & Montreal Railroad, which could be taken at half-price, and boats to take viewers to the lake and back. Elkins, seeing something special enough in the event to turn a profit for him even after paying the expenses, rightly anticipated that hundreds would be drawn by the spirit of the race.

Though word had spread, the cultural significance of this moment was still unknown; while the event was novel and exciting, it was impossible to foresee the future significance of college sports in American culture. A New York newspaper, in what can now be seen as a moment of profound underestimation, declared that intercollegiate athletics would “make little stir in the world.” Beyond Elkins, one other man perhaps perceived the spirit of America in the event: future President Franklin Pierce. Pierce, New Hampshire’s “favorite son,” who was at that time campaigning in the area, saw a golden opportunity to meet potential voters over a new contest in American sport. It would be he who would present the trophy oars to the winning crew.

Shortly after Yale’s commencement on 29 July, the crews of the two universities made their way to Weirs Landing in New Hampshire, where they were then conveyed by the Lady of the Lake to Center Harbor. In the summer air, they enjoyed days of sport and recreation, fortifying themselves for the race to come:

Arriving on a Friday, the three crews from Yale and the one from Harvard practiced the next day among vacationers lounging on house boats on the lake and under snowy sails tacking across the bay. On Sunday, they of course observed the Sabbath, strictly kept by most mid-nineteenth-century Americans of their social status. When Monday came, the day before the meet, the crews practiced again in their large and heavy-keeled boats, which one person likened to whale boats. The Yale men were concerned enough with their diet to abstain from pastries. The Harvard men appeared to be less careful. On the day of the meet, there were actually two races, one in the morning, a practice race of one and a half miles to give an idea of boat speeds, and the two-mile contest in the afternoon. The Harvard crew won the morning race in about seven and a half minutes. Returning to the wharf, the friends of the Harvard rowers, one crew member recalled, ‘immediately seized us and took us to their rooms, where we were regaled with ale, mineral water, and brandy.’ They then ate a hearty meal, and ‘after a little rest and a cigar,’ returned to the wharf, and were taken to the starting line for the 4 o'clock start of the official race.

The crowds had amassed and were treated to music provided by the Concord Mechanics’ Brass Band. As Thomas C. Mendenhall describes it, the boats were “backed up to the line: the vermilion-hulled Oneida with its oarsmen dressed in white shirts with blue trim; black Shawmut, the men in white edged with red.” At the sound of a bugle, the boats took off, and though the Oneida started off slowly—perhaps with the Harvard men still overcoming their brandy—the crew quickly gained strength and speed, overtaking Shawmut and prevailing over Yale by two lengths. According to the New York Herald, the crowd roared and waved from the shore, their cheers carried aloft by the melody of the brass band across the lake. The crews set aside their oars, returned to shore, and Harvard was presented with these very trophy oars by Franklin Pierce.

That evening, the crews were celebrated with a festive gala dinner and dance. They would remain on the lake for several days, enjoying the beginnings of summer—rowing on the lake during the days and rejoicing in the evenings—before taking Elkins’ trains back to their universities.

“Eight hearts must beat as one in an eight oared shell or you don't have a crew!”

The Future of the Race

Despite these auspicious beginnings, it would be more than a decade before The Race became an annual event. In the intervening years, however, the popularity of intercollegiate rowing contests spread to other universities. Harvard and Yale had looked across the pond to Oxbridge students for their inspiration; and now the rest of America began to imitate the two Ivy League schools, with competitive rowing clubs and competitions popping up at Brown, Penn, Dartmouth, Amherst, Bowdoin, Trinity, and elsewhere, throughout the 1850s. Harvard and Yale would regularly compete with these other universities, but it was not until 1855 that the two would meet again for the next official Harvard-Yale Regatta.

The second Race came almost as a surprise. To celebrate Independence Day 1855, the town of Springfield, Massachusetts decided to hold a boat race on the Connecticut River and invited all of the rowing clubs at Harvard and Yale to compete. While both universities accepted, Harvard canceled the night before. Yale seemingly did not take this lightly, as they issued an immediate challenge:

“The Boat Clubs of Yale having expected to find at Springfield, on the 4th of July, the Boat Clubs of Harvard, and having been disappointed in their expectations, do hereby challenge said Clubs of Harvard to meet them for a rowing match, at any place between Cambridge and New Haven, at any time between now and the 22nd of July.”

Harvard accepted, and the second regatta would take place in Springfield on 21 July. The Crimson again prevailed, as they would in the next two regattas, in Worcester in 1859 and 1860. And though it seemed like The Race might become an annual event in these years, the competition was forced to be put on hold.

While the eruption of the Civil War—in which several members of the original rowing crews would serve—undoubtedly sent shock waves throughout the universities, The Race was paused primarily due to the institution of a ban on the regattas by Yale from 1861 to 1864. In 1860, the intercollegiate competitions had aroused such enthusiastic student participation that they expanded across all domains of student activity—including a Harvard-Yale chess match, a Harvard-Yale billiards competition, among others—and their attendant festivities seemed to be getting out of hand.

As drinking, partying, and gambling became prevalent elements of these competitions, Yale decided that it needed to crack down and instituted a ban on all future regattas during the school year. The two universities attempted to find a solution, suggesting that they compete following the end of the term. But summer vacation began two weeks earlier at Harvard than at Yale, and with the Harvardians unwilling to give up any precious vacation time for the regatta, The Race was put on indefinite hiatus.

This moment marked, in many ways, the end of the formative stages of intercollegiate sports, and the genesis of college athletics as we now know them. While the country was torn apart by the Civil War, American sport and outdoor pastimes grew, organizationally, at a rapid pace.

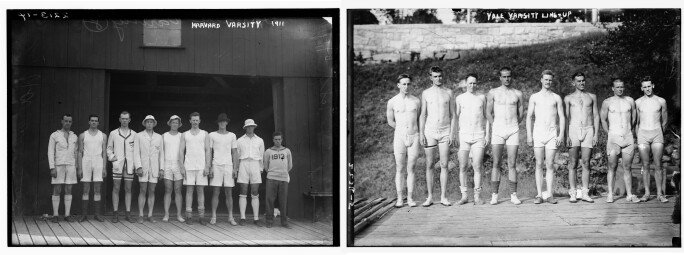

This period saw the rise of the professionalization and an increase in the intensity of training. The 1864 regatta, the first following the ban, featured a dramatic change. Yale, seeking to at last gain dominance over Harvard, heavily invested in revitalizing their boathouse and equipment, but further sought to hire a professional coach who would usher in a new era. In 1864, they hired William Wood, a physical education instructor from New York City, to train the oarsmen. Under his training, the Yalensians prevailed over Harvard—by more than 60 seconds—for the first time in that year’s regatta.

From this point on, this trend of professionalism, increased organization, and much more rigorous training molded what had previously been a series of loosely organized, competitive matches into a robust athletic program. And conjoined with that cultivated seriousness was an increase in the intensity of the rivalry. Harvard and Yale students would antagonize each other through song, pranks, and even outright physical conflicts, with police having to be called to the regattas on several occasions. But it was also in the growth of these tensions that The Race began to assume its stature.

The Harvard-Yale Regatta became an annual event following Yale's victory in 1864; over approximately 25,000 people regularly attended the regattas each year throughout the late 1860s. Since then, it has become the longest-running intercollegiate athletic event in the United States, only interrupted five times since then—and its interruptions have primarily been due to world-scale events, such as World War II and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It is hard work to make that boat go as fast as you want to. The enemy, of course, is resistance of the water, as you have to displace the amount of water equal to the weight of men and equipment, but that very water is what supports you and that very enemy is your friend. So is life: the very problems you must overcome also support you and make you stronger in overcoming them.”

Rowing Today

The first Harvard-Yale Regatta was a uniquely American affair in its synthesis of competition and entrepreneurship. An event that blended commercial enterprise, athleticism, and politics, the first Race encapsulates, even in its nascent form, all of the elements that define American sports today. Yet it also, if more quietly, featured two other definitive aspects of the American ethos, which have remained central to intercollegiate athletics: freedom and egalitarianism.

Organized sport began in the nineteenth century as one way in which students could exercise their freedom—from their highly routine schedules and the strictures of academic life—and cautiously rebel against the authority of their universities. Indeed, the Laws of Harvard College, codified in 1655, declared that “noe undergraduate upon any pretense of recreation … shall be absent from his studies,” and the pre-Revolutionary Laws of Yale College stated, “If any Scholar shall play at Hand-Ball, or Foot-Ball, or Bowls in the College-yard, or throw any Thing against the College, by which Glass may be endangered ... he shall be punished six pence.”

While rowing—and the academy writ large—was open exclusively to men for most of its history, the principles of egalitarianism were nonetheless at the forefront of early intercollegiate sports. In post-Revolutionary America, student riots at universities were rampant—in fact, according to Ronald A. Smith, at “no time in American history were campus riots more common in the period following the Revolutionary War until the mid-nineteenth century.” The paternalism that students found at universities—inherited from their European progenitors—seemed to exist in direct contradiction with the principles of egalitarianism that the United States was founded upon. If the intellectual lives of students were to be rigorously controlled by their professors—indeed this period saw the introduction of even stricter laws and the banning of liberal books, as faculties feared the influence of the French Revolution—they would then keep the rebel spirit alive in their extracurriculars. It was in sport where they would find a place to express themselves and compete, as equals, with one another.

As organized sports have become central to American universities, that foundational principle of freedom in athletics has been extended to afford massively increased opportunities for any student to participate in competitive sports, at both the intercollegiate and intramural levels. Rowing, in particular, exemplifies this development, as women’s rowing has ascended to a stature without precedent in American sports. Wellesley was the first university to organize a competitive women’s rowing team in the late nineteenth century, long before any other campus. Today, the NCAA permits Women’s Division I rowing teams to grant the equivalent of 20 full scholarships to athletes. Not only is this the most for any women’s sport, it is the second-highest allocation for any American intercollegiate sport—only football offers more scholarships.

It was the introduction of Title IX in 1972 that reshaped the landscape of collegiate rowing and facilitated the rise of women’s rowing in the United States. While some universities already had women’s crew—notably Yale—the teams were not nearly funded to the same level as the men's crews prior to the introduction of Title IX. Rowing, with its attendant expenses—a boathouse, oars, the boats themselves—required greater financial backing in order for athletes to be adequately competitive. Though many school’s women’s teams were as competitive as the men’s teams, they were made to utilize older boats, while the men would receive state-of-the-art equipment.

A series of protests around Title IX took place at Yale in 1976, and the national attention they received put women’s rowing on the map. The first Olympic Games that followed the introduction of Title IX—the 1976 Montreal Summer Olympics—inaugurated the first women’s Olympic rowing competition, and the United States, represented almost entirely by collegiate or formerly collegiate rowers, including Anne Warner from Yale, took home the bronze.

As time has passed, this legacy only continues. The United States National Women’s Rowing Team’s eight won the gold medal at each summer Olympics from 2008 until 2020, and won the World Rowing Championships from 2005 until 2016. The dominance of American women’s rowing is nearly unmatched at the international level; its only precedents are the United States Men’s National Basketball Team, which was undefeated in the Olympics from 1936-1968, and has won sixteen of eighteen gold medals, as well as the Soviet Union's men's hockey team from 1963-1976, which won fourteen titles in those years. Among contemporary American teams, there is no competition.

“When you step into that boat you have made a silent commitment to your team that you will do everything in your power to help them win.”

As access to the sport spreads beyond the Ivy League and throughout public universities, both its appeal and its stature as a competitive sport have grown. In this way, the story of rowing in the United States is the story of the championing of American democratic values. From its very inception, intercollegiate rowing contained the groundwork for all that was to come—its affirmation of the benefits of the competitive sporting spirit and its claims to freedom from paternalism.

Now a multi-billion dollar industry, intercollegiate sports compete with professional athletics for prime television slots, demanding attention equal to any other national sports competition in the country. College football season defines fall and winter in the United States, and March Madness dominates the spring, with this year's NCAA Tournament averaging over 10.7 million viewers for each game.

The grand American story of intercollegiate sports—its rivalries, historic games, remarkable victories, and crushing defeats—traces itself through the history of this country to these 1852 Trophy Oars. Symbolizing the birth of a uniquely American phenomenon, these oars contain within them the very spirit of American enterprise.