In 1922 Kandinsky joined the teaching staff at the Bauhaus, where he would remain for over a decade. A radically progressive establishment, the Bauhaus was dedicated to the pursuit of aesthetic theory and as a gathering place for many of the key figures of Modern art and design in Germany it provided the perfect backdrop to Kandinsky’s own theoretical and artistic experimentation.

‘The form, even if entirely abstract and resembling a geometric figure, has its inner harmony and is a spiritual being with characteristics identical to it.’

Painted two years after Kandinsky arrived there, Strich Zentraler embodies the distinctive character of his work from his period. By the time he started at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky was already moving towards a more geometric abstraction, in part influenced by his years working alongside the Suprematists in Russia during the First World War. Frank Whitford considers the shift in the artist’s work of the early 1920s, writing: ‘The works of the Bauhaus period have a distinctive and specific character. ‘Energy, previously reflected in the attack with which the marks and colours were set down, is now conveyed by a dynamic tension between the compositional elements. It is as though the conflict between the cerebral and the emotional, a constant factor in his painting and thinking, has been resolved, however temporarily, in favour of the cerebral’ (F. Whitford, Kandinsky. Watercolours and other Works on Paper, London, 1999, p. 69).

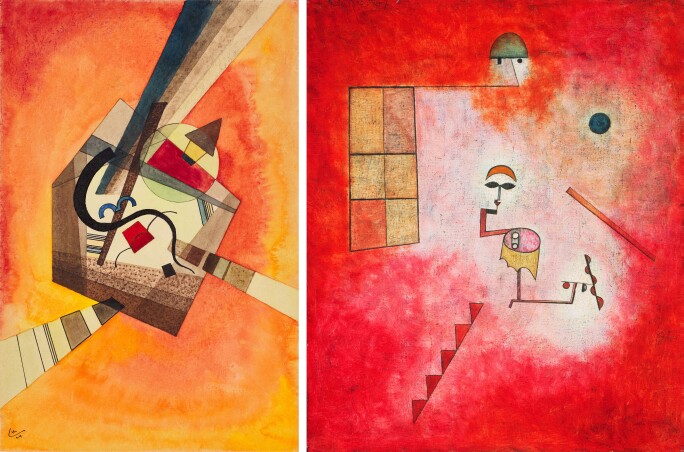

This is certainly true of Strich Zentraler which has a powerful yet considered centrifugal force. The central line of the work’s title appears almost as a ray of light or a visual spectrum and both anchors the central image and provides its propulsion. The crisp clarity of the composition’s core recalls works of the previous year but now, rather than isolating this image on a blank sheet or primed canvas, Kandinsky surrounds it with a soft profusion of colour, as seen in other works from 1924 (fig. 1). This was entirely in keeping with his conception of colours as having distinct characteristics moderated by form. As early as 1911, in his seminal text Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky had described this: ‘It is evident that certain colours can be emphasised or dulled in value by certain forms. Generally speaking, sharp colours are well suited to sharp forms (e.g. yellow in the triangle), and soft, deep colours to round forms (e.g. blue in the circle). But it must be remembered that an unsuitable combination of form and colour is not necessarily discordant, but may with manipulation show fresh harmonic possibilities’ (quoted in Paul Overy, Kandinsky. The Language of the Eye, London, 1969, p. 163). The harmonic possibilities are evident in Strich Zentraler where the contrast of the fiery surrounds with the cool centre the only add to the compulsive energy of the composition.

Right: Fig. 2, Paul Klee, Prestidigitator (Conjuring Trick), 1927, oil and watercolour on fabric laid down on card, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia © 2022. Photo The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

In this respect, the work also illustrates the close friendship between the Russian and his fellow-artist Paul Klee. The two men taught together at the Bauhaus from 1922 and, following its relocation from Weimar to Dessau in 1926, lived together in the estate designed by Walter Gropius. Their shared concern with abstraction and spirituality within art often resulted in similar compositions, which in turn reveal the flow of their dialogue (fig. 2). The fine mist of watercolour that illumines the present work was a technique adopted from Klee; in allowing for a gradual shift between colours it opened up new possibilities and resonances that would be influential not only in Kandinsky’s work but also for a new generation of artists (fig. 3).

The atmosphere of mutual experimentation and learning fostered by the Bauhaus was of huge importance to the Kandinsky, allowing him to consolidate his ground-breaking experiments with abstraction from before the First World War. However, the importance of Kandinsky’s artistic friendships is evident not only in the genesis of this picture, but also in its subsequent history. It was given by the artist to his friend and contemporary Alexej von Jawlensky in February 1925. The two artists first met in Munich in 1896-97 and became firm friends. Jawlensky and his partner Marianne von Werefkin spent the summers of 1908-1910 in Murnau working alongside Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter, and the collaborative spirit of these summers would prove pivotal for both artists. Together they formed first the Neue Künstlervereinigung München and then, when that proved too traditional, they founded Der Blaue Reiter, pioneering an approach to art that would become known as German Expressionism. A testament to the strength of their friendship, Jawlensky kept the present work for the rest of his life and indeed it remained with his descendants until the mid-1980s when it was sold to the Leonard Hutton Galleries in New York. It was acquired there in 1993 and has been in the same private family collection ever since.