The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Image: © Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

Artwork: © Alberto Giacometti 2022/DACS, London

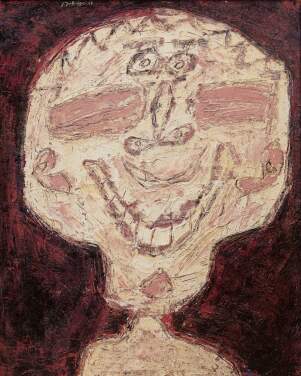

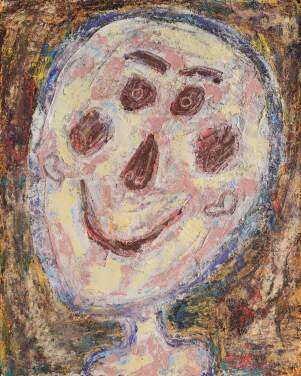

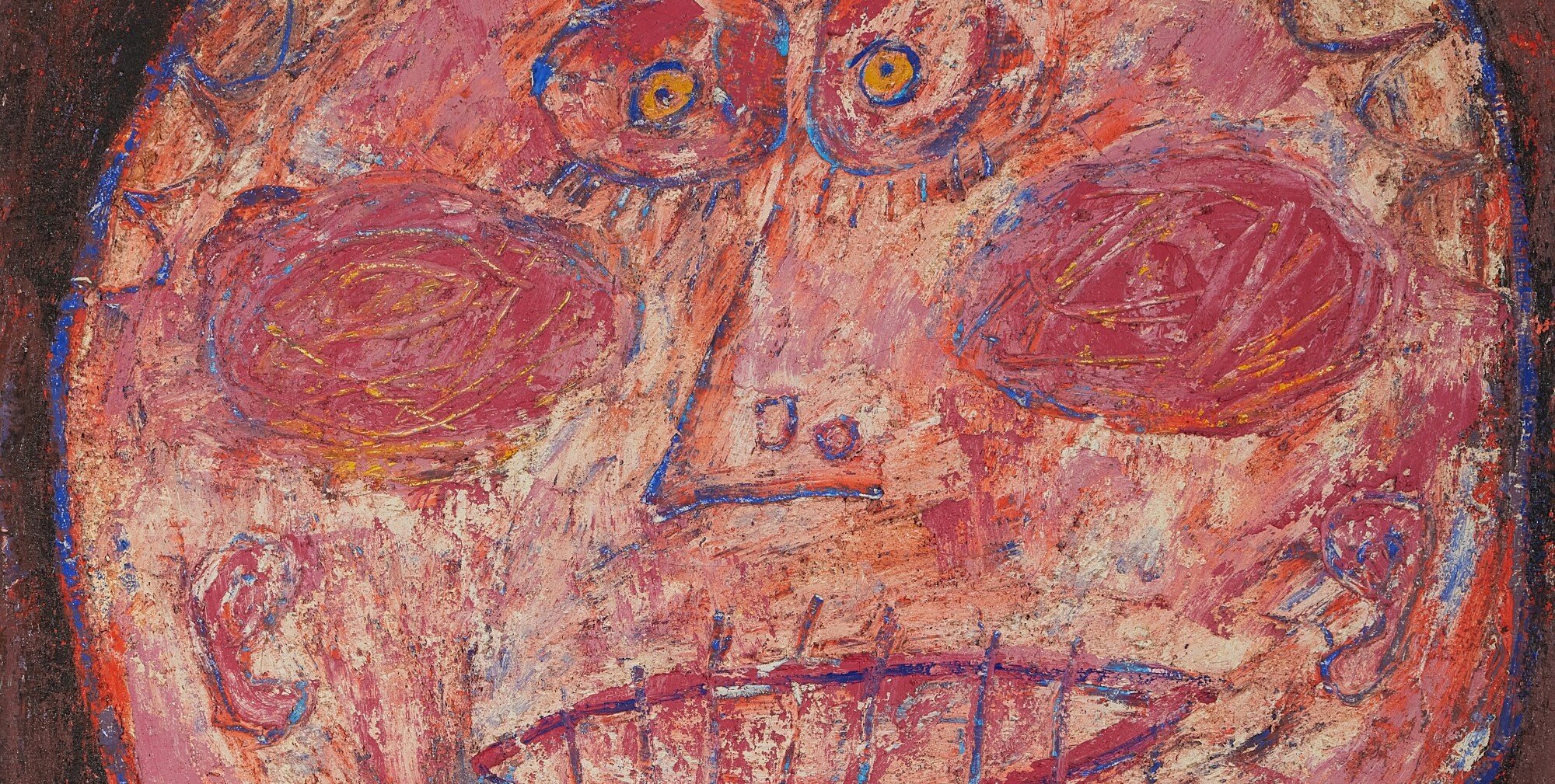

In jubilant hues of pink, crimson, cobalt and orange, Sourire (Tête hilare II) (Smile (Hilarious Face II)) is testament to Jean Dubuffet’s radical art brut style, and his enduring protest against conventional standards of beauty. Belonging to Dubuffet’s Grandes Têtes of the Roses d’Allah series, a cycle of six large-scale portraits executed between May and June 1948, the present work demonstrates the extraordinary range of techniques and media employed by Dubuffet at a pivotal, early moment in his career. The Roses d’Allah paintings are highly textured, their surfaces heavily worked in thick, rough brushstrokes. Drawing upon the visual language of urban graffiti and tribal art, Dubuffet’s quintessential caricatured figuration saw the artist reject traditional portraiture, taking a distinctly ‘anti-art’ position at a moment when the Parisian intelligentsia and the artists they supported were thriving after the end of the traumatic Second World War. Depicting an exuberant, smiling female sitter, the present work underscores the simple hopes and joys of post-war life, and the intimate, every-day moments that were all but impossible during the turbulent years of war. Measuring 92 by 73 centimetres, Sourire (Tête hilare II) ranks among the largest and most resolved iterations of the Roses d’Allah series, comparable only to La Bouche en croissant (1948), a gift from great collector and president of The Whitney Museum of Art, David Solinger to the collection of The Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, where the painting now resides. The provenance of Sourire (Tête hilare II) further attests to its importance within Dubuffet’s early output, as it was a formative part of the collection of E.J. Power who in the late 1950s was of one of Britain’s most important, early collectors of contemporary art. Power greatly admired Dubuffet, and acquired over eighty works by the artist between 1955 and 1960, which sat in his collection alongside works by the great American Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Ellsworth Kelly. Encapsulating the distinctive styles of Informel, art brut, and art autre dominant in lively Paris during the late 1940s and prevalent across Dubuffet’s wider oeuvre, Sourire (Tête hilare II) is a radical, painterly triumph.

Jean Dubuffet’s Roses d’Allah series:

The present work exemplifies a naïvely rendered head of a woman, her anatomically disproportionate face caught in a moment of animation and pure joy. Her round face has the appearance of being compressed and wedged into the picture plane, a compositional element inherent to Dubuffet’s early graphic vernacular in the genre of portraiture. Set against a muted background, this exquisite, smiling figure suggests the post-war economic boom in Europe, and indeed the Parisian bourgeoisie’s return to normality and leisure after the war. Here is a woman captured in an intimate moment of joy and celebration; Sourire (Tête hilare II) is thus an image of euphoric exuberance, of elated hopes for a fruitful future, and the newly found joy of everyday life. As part of the Roses d’Allah series, the six Grandes Têtes executed between May and June 1947 were painted alongside Dubuffet’s Portraits, Arabes, a body of work inspired by the artist’s trip to Algiers and his travels through the Sahara in February 1947. While the figures of the Grandes Têtes have a distinctly Parisian look and are evocative of Dubuffet’s early Mirobolus portraits of 1945, the works employ the same vibrant colour palette in hues of contrasting pink, blue, and orange in paintings such as Arabe a L’oeillet and Bedouin sur L’Ane (both painted between May and June 1948).

The Informel movement signified a shift towards formlessness, abstraction, and a crucial emphasis on the artist’s chosen materials and media. Dubuffet described this in ‘Notes for the Well-Read’, a letter written to a circle of his closest friends – writers and philosophers – during the summer of 1945. He discussed the active and expressive role of materials, a role that was critical in the development of the theory and practice of art brut: “He argued that art should be the product of a competitive interaction between the artist, his tools and his medium, and that the finished work should retain the marks of that struggle. He favoured difficult, intractable materials because they heighten the adventure for the artist and introduce the element of chance” (Frances Morris cited in: Exh. Cat., London, Tate Gallery, Paris Post War: Art and Existentialism 1945-55, 1993, p. 79). Dubuffet himself explained the crucial materiality of his work: “The essential gesture of the painter is to cover a surface… to plunge his hands into full buckets or bowls, and with his palms and fingers to putty over the wall surface with his clay, his pastes, to knead it body to body, to leave as imprints the most immediate traces of his thought, the rhythms and impulses that beat in his arteries and run along his nerves” (Jean Dubuffet cited: Exh. Cat., London, Tate, Paris Post War: Art and Existentialism 1945-55, 1993, p. 33). Sourire (Tête hilare II) exemplifies this highly gestural, frenetic application of media, its surface revealing Dubuffet’s thick brushwork, but also the use of a knife, or the end of the brush to scratch away areas of thickly built up pigment.

Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo

Image: © Albright Knox Art Gallery/Art Resource, NY/Scala, Florence

Artwork: © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022

At the time the present work was created, Europe was still recovering from the impact of the Second World War. Executed only three years after the Liberation of France, the present work exemplifies an artist confronted with profound angst, consumed by the need to rid visual art of its affected heroics and cultural inhibitions. Alongside other artists active in Paris in this decade, particularly Wols and Fautrier, Dubuffet embraced an intuitive style that championed spontaneity and uninhibited creative expression, while rejecting traditional Western ideals of beauty and skill. Influenced by Hans Brinzhorn’s book Artistry of the Mentally Ill, Dubuffet coined the term Art Brut, meaning “raw art” or “outsider art,” as his classification for a mode of art produced by non-professionals working outside the aesthetic norm. Categorically opposed to "cultivated" art taught in schools and museums, Dubuffet endeavoured to "unteach" himself everything he had learnt while studying painting at the Académie Julian in Paris, and in so doing, rediscovered a potent vision of the world. In his quest to forge an entirely innovative artistic language, one that was unconnected to conventional Western traditions, Dubuffet was especially drawn to so-called “primitive” art, as well as that produced by children and sufferers of mental illness. Dubuffet himself noted in 1962, “It pleases me to protest against this aesthetic, which I find miserable and most depressing. Surely I aim for beauty, but not that one… People have seen that I intend to sweep away everything we have been taught to consider – without questions – as grace and beauty… but [they] have overlooked my efforts to substitute another and vaster beauty, touching all objects and beings, not excluding the most despised – and, because of that, all the more exhilarating” (Jean Dubuffet, “Landscaped Tables, Landscapes of the Mind, Stones of Philosophy”, in: Exh. Cat., New York, The Museum of Modern Art, The Work of Jean Dubuffet, 1952). Dubuffet believed that these modes of visual expression were closer to the truth of the subliminal unconscious, resulting in a more realistic artistic language devoid of unnecessary aesthetic ornamentation. This, with its naïvely rendered figure capturing a universal feminine essence, the tenets of Art Brut, as well as Dubuffet’s own inventive painterly mastery, find their earliest expression in Sourire (Tête hilare II).

Image: © Robert DOISNEAU/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images Robert DOISNEAU/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

“Dubuffet was a self-proclaimed iconoclast, consciously looking for ways of breaking the mould.”

A significant work within the Roses d’Allah series, Sourire (Tête hilare II) exemplifies the aesthetic language of the Informel, in which traditional conceptions of beauty are addressed, and indeed invalidated. As Selz noted, “These figures of 1945 to 1946 are shocking only if approached with preconceived notions of classical ‘beauty.’ Ugliness and beauty do not exist for Dubuffet as he becomes fascinated with the relation of nature (his material) to man (the emerging image)” (Peter Selz, “Jean Dubuffet: The Earlier Work”, in: Exh. Cat., New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Jean Dubuffet, 1962, p. 30). Executed at a moment of renewed hope and aspiration in Paris, this exuberant, early portrait exemplifies Dubuffet’s investigation into quotidian life, in turn affirming the artist’s unfailingly optimistic commitment to capturing the uplifting resolve of the human spirit at the close of the Second World War.