Themes of vision and perception, as well as the re-imagining or fragmentation of the human figure, were instrumental to Surrealist philosophy and a primary mode of artistic experimentation throughout René Magritte’s oeuvre. Yet in no work is his investigation into the matrix of visual perception more dynamically engaged than in his 1963 canvas, La Traversée difficile. From the bilboquet, to the cyclopic eye and the suited-figure, the present work is a triumphant tour-de-force of the artist's most iconic and recurrent motifs. With them, Magritte weaves together an image which oscillates between beguiling metaphor and exacting critique, brought to life in the incomparably matter-of-fact painterly language for which he has come to be so celebrated.

Magritte first ideated the theme explored in La Traversée difficile in a work by the same name executed nearly forty years earlier in 1926 (see fig. 1). In this earlier version, Magritte paints only one figure, a bilboquet, situated within a close interior which teleports away from the viewer at an exaggerated steep perspective. Despite the anthropomorphic addition of the single eye on the bilboquet's "head", the totem appears distinctly inanimate amidst the other architectural elements which fill the room. In 1963, Magritte makes the decisive choice to reimagine the totemic object in the guise of a suited figure, a motif which stands among the most iconic within his visual lexicon; perhaps most importantly, the eye overtakes the head entirely. The bilboquet becomes a secondary actor, something of an anthropomorphic echo to the human body in the foreground which further confuses the sense of comfortability with the composition as a whole.

Right: Fig. 3 Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Shipwreck, 1805, Tate Britain, London

In title alone, the work presages a kind of crisis of the human condition or mind. As with many of Magritte's works, the title is left invitingly yet intentionally ambiguous, a kind of multifarious non-sequitur which implies yet does not define its meaning. The "difficult journey" to which Magritte here refers can on the one hand be read explicitly, in the tumultuous stormy seascape, whose waves violently crown and crash above the stone baluster dividing the fore- and backgrounds. The crashing waves in the present work were modeled after the marine painter Wartan Mahokian’s La Vague, a postcard of which Magritte kept in his studio and referenced in numerous compositions (see fig. 2). Just below the horizon, Magritte poignantly includes a ship being overtaken by the white-capped waters, offering both an iconographic and thematic echo of a recurring theme within the epic works of the 19th century Romantics (see fig. 3). Whereas in the 1926 composition, Magritte leaves ambiguous whether this vignette is seen through a window or a painting, here the ocean encroaches onto the scene, rising like a wall behind the protagonists. In Magritte's paintings more generally, the ocean often represents a sense of mystery, abyss, or the unknown, symbolizing the vastness and unknowability of existence. It can also depict alienation or a longing for escape, and in some cases, can be interpreted as a metaphor for the subconscious mind, where feelings and emotions are hidden. As such, the cataclysmic seascape in the present work portends a metaphysical journey as well, a harbinger of a crisis of perception which proliferates upon consideration of the other elements within the composition.

“At least it hides the face partly well, so you have the apparent face, the apple, hiding the visible but hidden, the face of the person. It's something that happens constantly. Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.”

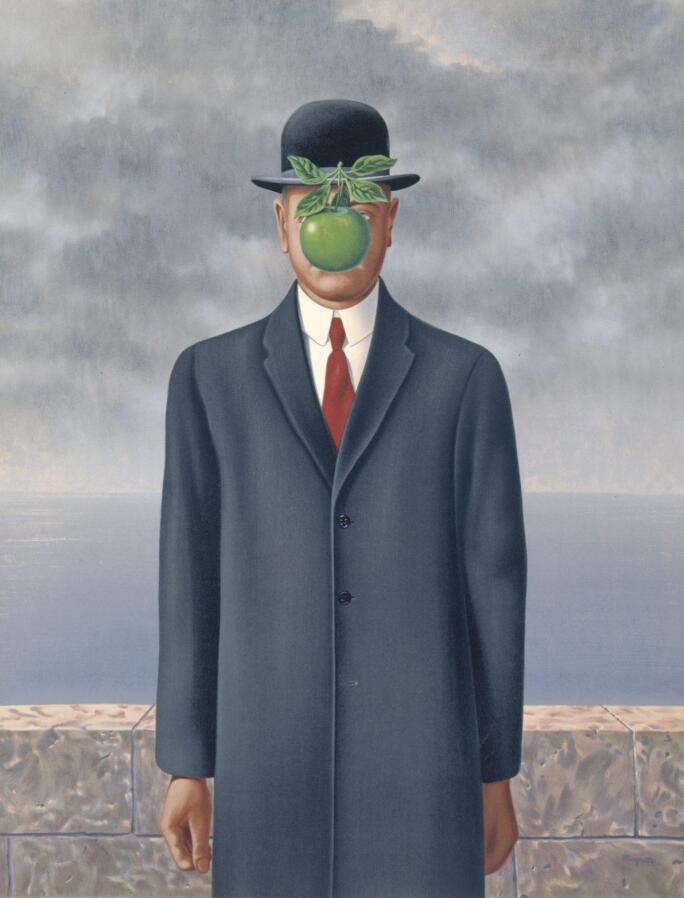

Magritte invariably employed the suited figure as a cipher for the generic, everyday man, here with a head supplanted by a cyclopic, all-seeing eye. While this form of “faceless man" famously appeared throughout the artist’s works from the 1960s (see fig. 4), what makes La Traversée difficile so intriguing in their context is that the eye does not simply hide but rather replaces the head entirely. A few years later, in 1965, Magritte would go on to explain that his preoccupation for these works lay with our pressing fascination to see beyond the world of appearances. As he describes, “there is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us” (quoted in Harry Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, New York 1977, p. 172). But in creating a hybrid between the thing which hides, the eye, and the thing which is hidden, the figure’s head, Magritte collapses any possibility to see beyond either element. Whereas in Son of Man, Magritte leaves enough visual detail for the viewer to comfortably assume that the head remains intact behind the apple which obscures it, here they have no such reassurance. Where the eye peeks out from behind the apple in Son of Man, it here overtakes, and the head undergoes an irreconcilable transformation which no amount of mental agility can undo. What we are left to grapple with is our expectation of a head, as we know it to look, and the way it appears presented before us on the canvas.

The conception of the eye as a (dis)embodied actor finds precedent in earlier works from Magritte’s oeuvre. David Sylvester suggests that the choice of imagery may have been inspired by Odilon Redon’s Le Fantome (see fig. 5). The macabre and often uncanny imagery which courses throughout Redon’s work is often acknowledged as precursor to Surrealism more broadly, but the imagery in his 1878 drawing bears a particularly striking similarity to Magritte’s first iterations on the theme. As is viscerally felt within the present work, the effect of this anatomical isolation was two fold. On the one hand, by removing all extraneous features from the figure’s face, Magritte poises the imposing, cyclopic eye as an omniscient, all-seeing power.

Fig. 7 René Magritte, The False Mirror, 1929, Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2025 C. HERSCOVICI, BRUSSELS / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

In both his 1937 canvas, Le Monde poétique, and his 1929 canvas, The False Mirror, the eye serves as the protagonist (see figs. 6 and 7). In the former, the round pupil and bright white which surrounds it work to convey a sense of shock at the sight of the viewer. Already positioned as an adversary, the viewer is made to feel the scrutiny of the eye’s unbroken, frontal gaze. In the latter, the eye and what it sees become enmeshed, and the viewer in turn becomes involved in a mysterious and oblique reflection, a tangential feedback loop. For Magritte, the painted eye had a poignant psychoanalytical significance, particularly in its capacity to invoke self-reflection, or perhaps even abjection, on the part of the viewer. As Belgian writer and surrealist Marcel Lecomte observed; “often, these objects seem to be looking at us. What event are they waiting for, unless it is that of the mystery of their meeting on the same canvas, the mystery of their close combined identity? Then they exert all their restrained tension on us, all their charm, all their mute confidence. And so there is a secret movement between the painted and the spectator; what the objects represent leads us back towards ourselves (Exh. Cat., London, The South Bank Centre, Magritte, 1992, p. 37).

Magritte's subversion of the fundamental properties of anatomy were an extension of his fascination with "Objective Stimulus," a term he applied to those instances in which he replaced an object familiar to a particular context with one related to it, but out of place. The shock of dissonance where one expects there to be consonance, Magritte realized, was all the more unsettling than the reverse. This framework was something of a departure from the prevailing Surrealist preoccupation with the revelatory potential held within the combination of disparate objects. With it, however, Magritte opened a trove of new pictorial and conceptual possibility. When dissected into its component parts, all of the elements Magritte uses to describe the figure are to be expected of a portrait. In other words, it is not the eye that is shocking but the way the eye appears. And in transforming the eye into the very thing which inhibits our ability to see the figure as we expect it to appear, Magritte raises a tantalizing paradox between vision and perception.

Once established in the central figure alone, this crisis of viewership is further complicated by the introduction of a second: the totemic figure of the bilboquet. First emerging in the artist’s work around 1926, the bilboquet began to take on an increasing anthropomorphic character in the 1940s (see fig. 8). This evolution toyed with the term’s dual meaning, invoking the Surrealist penchant for wordplay: as a noun, Bilboquet refers to a popular stick-and-ball game by the same name, and as a proper noun, it also refers to a character from the circus troupe of Saltimbanques, archetypes of which would surface in the works of artists ranging from Daumier to Picasso. The ambiguous and unassuming bilboquet likely appealed to Magritte for its potential transfigurations; its form was phallic as well as evocative of the bishop in a chess set—a game often seen by the Surrealists as a psychoanalytic metaphor for life. As Ann Umland expounds, “It was a form with multivalent connotations, ranging from mannequins to balusters or table legs to chess pieces, and it would become one of Magritte’s stock elements, a distinctive ‘type’ that could be multiplied, resized and repositioned ad infinitum, each time slightly differently, posing a provocative challenge to prevailing definitions of originality in art” (Exh. Cat., New York, The Museum of Modern Art, The Mystery of the Ordinary, 2013, p. 28). In the present work, the form's human qualities are amplified through its doubling with the suited-figure which stands before it. In their composition parallel, Magritte calls upon the way that its chiseled, curvilinear form echoes the shape and presence of the human physique.

Right: Fig. 10 Girogio de Chirico, The Morning of the Muses, 1972, Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, Rome

This anthropomorphizing impulse was a recurrent theme throughout the broader Surrealist movement, particularly for those artists working in a visual language which deferred to but ultimately reinvented the visual material of our lived reality. In the work of Yves Tanguy, for example, his organic, distantly familiar visual language confers on the central elements a visceral materiality which lends to their personification, and extends so far as to influence our reading of the immaterial skyscape as having an anthropomorphic quality as well (see fig. 9). And yet, caught somewhere between liquid and solid, the shapes still elude categorization or neat description, thus heightening the feeling that Tanguy’s paintings occupy a world adjacent to but separate from our own. Giorgio de Chirico's iconography moves closer to Magritte's project in the distinctly figurative tenor of his motifs. In his 1972 canvas, The Morning of the Muses, de Chirico explores the same idea of doubling which Magritte here forefronts (see fig. 10). The juxtaposition between the impersonal yet uncanny faceless mannequin heads and the ornate classical bodies on which they are positioned likewise inspires a deeply metaphysical dilemma in the viewer. In La Traversée difficile, the distinctly human quality of both the suited-figure and its bilboquet shadow ultimately confuse a linear sense of personhood, and in turn work to show the bifurcated, or rather duplicitous nature of self perception.

This idea of doubling was a central tactic within Magritte's oeuvre at large, one which often functioned as a form of mental deception. La Traversée difficile is a tantalizing example of the measured hand with which Magritte at once offers up and withholds visual information. As in his 1937 self-portrait, wherein the artist pictures himself standing before a mirror which only reveals to the viewer the same image of the back of his head, Magritte here creates the illusion that each of the doubled figures stand to reveal those questions which the other leaves unanswered (see fig. 11). And yet, in paradoxically de-humanizing a human figure and anthropomorphizing the inanimate bilboquet, dissociating each from their typical contexts and instead setting them against the high-pitched pictorial drama characteristic of his most impactful compositions, Magritte evokes the quintessential Surrealist paradigm of questioning the incongruous relationship between our visual expectation and our mental perception of an image.

An Eye-Opening Look at René Magritte’s 'La Traversée difficile'