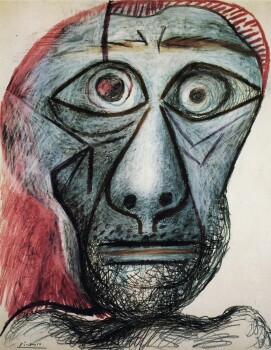

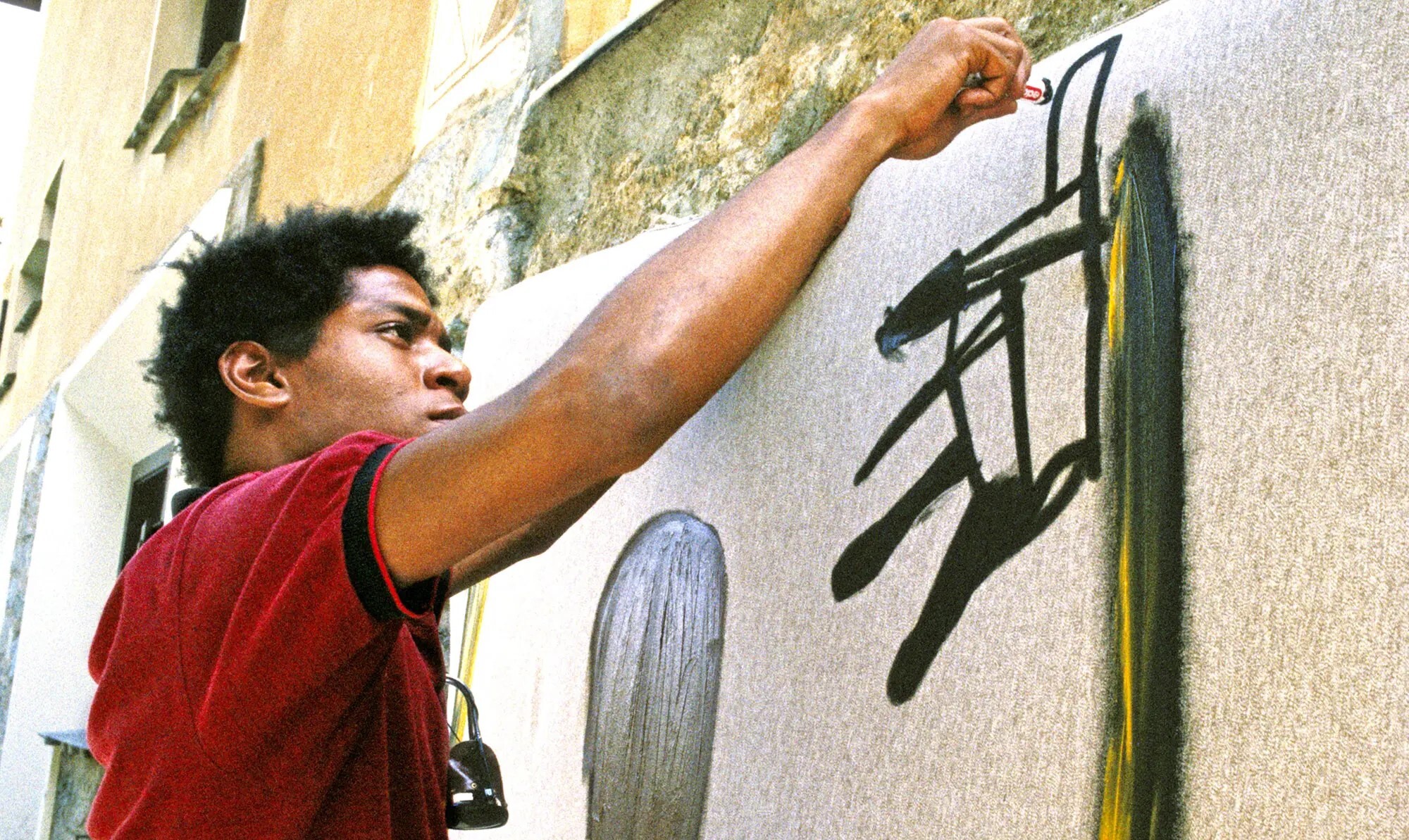

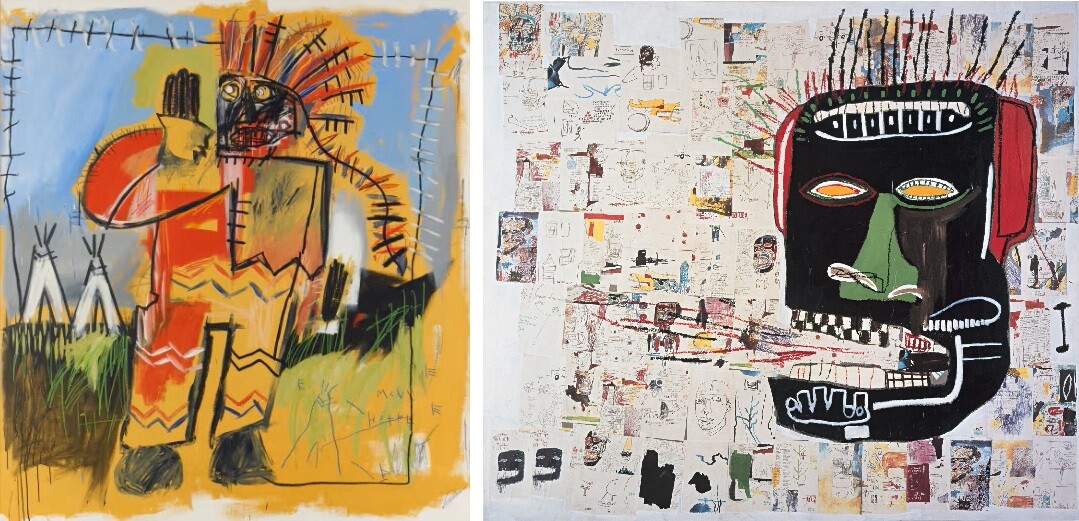

Captivating in its electric immediacy, Untitled (Indian Head) is a superlative example from Jean-Michel Basquiat’s most celebrated and enduring motif, the iconic skull-like head. The Heads, shaped with corporal density and fervent expression, act as both self-portraits and icons, occupying a central place in his most acclaimed masterworks. Executed in 1981, the critical year which heralded his ascent from SAMO©, the street provocateur, to the prodigy of the mainstream art world – during which time he also began producing artworks under his own name – Untitled (Indian Head) powerfully asserts Basquiat’s instinctive and lauded abilities as one of the greatest draughtsmen of the twentieth century.

Here, in an explosion of vivid colour and gestural fervour typical of his works on paper, the titular head is set against a flurry of arrows and crosshatches in a kaleidoscope of hues, pulsating with dynamic urgency. With exceptional fullness, the graphic intensity of the central figure is undeniably mesmerising, its presence intensified by Basquiat’s frenzied application of oilsticks – red, orange, blue, yellow, teal, and black markings burst forth with expressionistic fervour. Encapsulating the incredible dexterity and draughtsmanship that defines the very best of the artist's works, Untitled (Indian Head) is a heroic depiction that reflects the explosive talent and brilliance of its author.

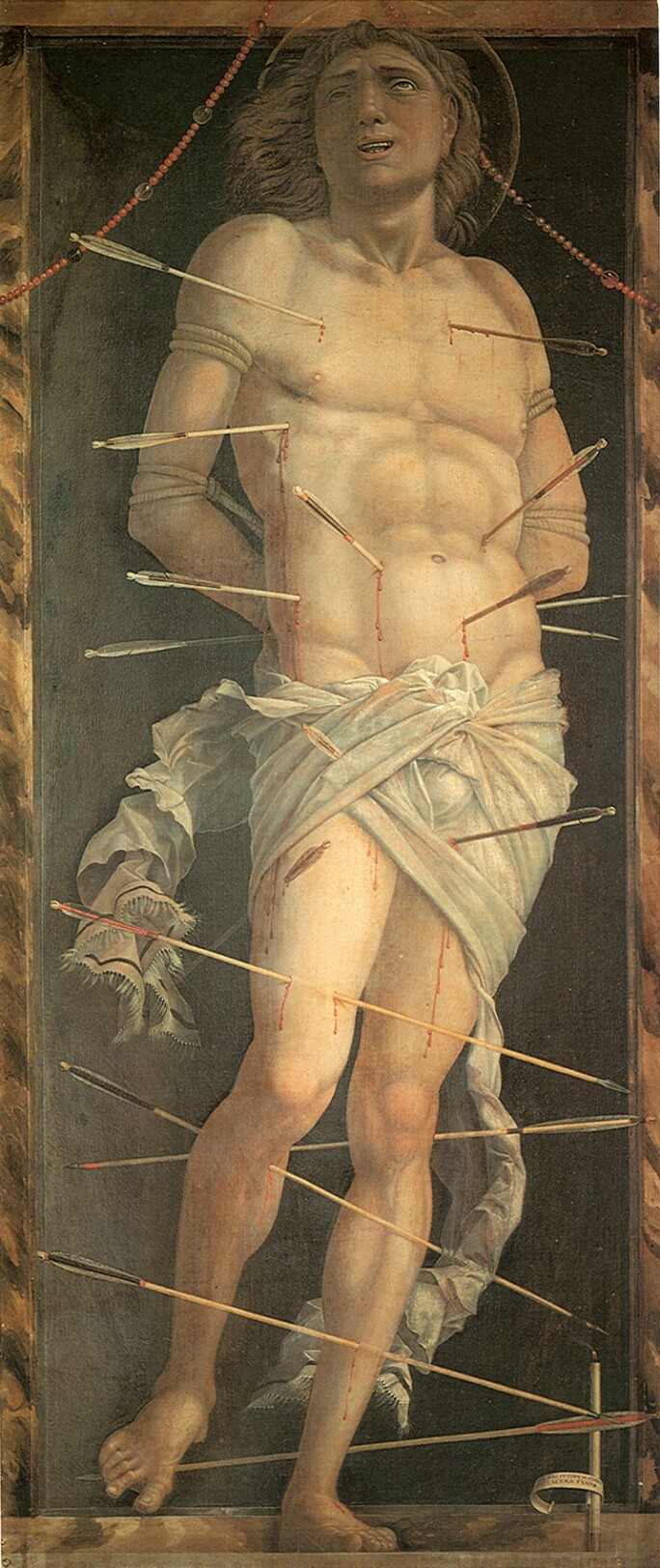

Numerous lines emerge from and surround the head in the present work – some resolve into the feathers of a war bonnet, others into flying arrows and tomahawks, while still others remain abstracted in crosshatches. Basquiat’s lexicon of cyphers and symbols in this work memorialises a similar visual strategy used by the First Nation cultures he references in the title: “the Indians used geometric forms in their paintings, figurines and masks. Here the head may be a circle, there a square and elsewhere a triangle… Thus forms do not represent appearances, but ideas” (Patrick Waldberg, quoted by Kirk Varnedoe in Exh. Cat., New York, Museum of Modern Art, Primitivism In 20th Century Art, vol. II, 1984, pp. 564-65). The symbolic resonance of the present drawing cannot be overstated; Basquiat's deep-rooted concerns about race, identity, and the accumulation of power and wealth are evident, and his repetitive layering transforms the arrow into a symbol replete with power, struggle and legacy. Coupled with the shamanistic skull and simultaneously connotative of centuries-old cave paintings and archery, the arrow has also long been used in cosmograms to signify direction and transformation. Thus, the present work can be seen as a depiction of a powerful warrior, a figure often used by Basquiat as a kind of self-portrait; dating to the early moment of 1981, amidst his meteoric rise to fame, Untitled (Indian Head) is thus a prescient proclamation of the artist’s grand ambitions.

In its appropriation of First Nation imagery, the present drawing formally recalls the work of early 20th century modernist Max Ernst, who, like Basquiat, drew inspiration from the myths and folklore of American, Latin, and Caribbean cultures. Ernst was deeply influenced by the Native American art and history he encountered in Sedona, Arizona, and the Southwest United States, where he lived with his wife, Surrealist painter Dorothea Tanning, between 1943 and 1957. In particular, the saturated hues his work adopted during this period can be directly traced to this influence; Basquiat likewise uses colour with symbolic intent. The colours of the Hopi (yellow and turquoise) Navajo (black, white, turquoise and yellow) and Apache (black, blue, yellow and white) peoples that influenced both artists are masterfully incorporated in the present work; Basquiat here stylises his arrows in the native cultures’ colours to pay homage to these formative groups.

Evincing an intense scrutiny and breathtaking intimacy, Basquiat’s works on paper comprise a fundamental element of his prolific oeuvre and are essential to a comprehensive understanding of the diverse signs, symbols, and subjects which make up his staggeringly inventive output. Simultaneously appearing in frontal and three-quarters view, the head in the present work possesses a Cubistic multidimensionality. Slit-like pupils peer out of widened eye sockets while the figure’s jaw structure is rendered doubly in red and turquoise, making it appear as though the face is perhaps peering through a mask. This multilayered depiction of sight has been regarded by scholars such as Fred Hoffmann as a way to bridge the physical and the psychological. Hoffmann notes:

“What drew Basquiat almost obsessively to the depiction of the human head was his fascination with the face as a passageway from exterior physical presence into the hidden realities of man’s psychological and mental realms…In the case of the eyes, they not only peer out as if seeing, but also invite the viewer to penetrate within.”

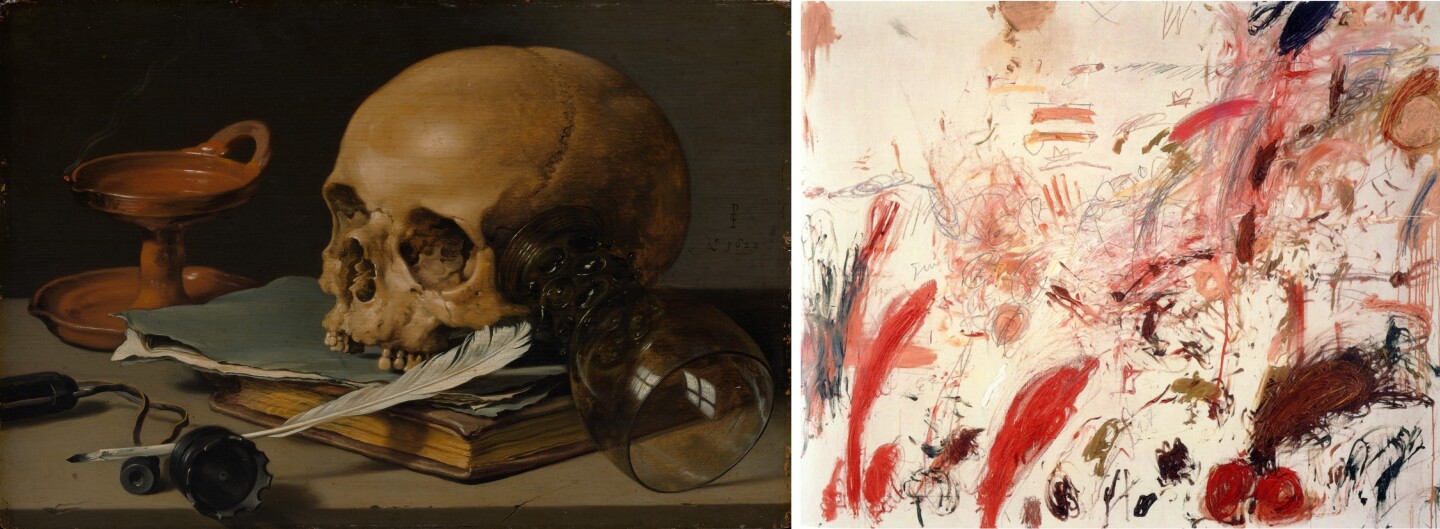

Right: Cy Twombly, Ferragosto IV, 1961. Private Collection. Art © Cy Twombly Foundation

The depiction of the mask-like head also represents Basquiat’s relentless exploration of cultural identity: the artist, who was born to a Haitian father and Puerto-Rican mother, often expressed his feelings of racialised otherness in a white-dominated art world. Basquiat’s use of the mask, a sacred object which historically functions in the Black diaspora as a mediator between the physical and spiritual realms, now becomes an unapologetic visual metaphor for black identity.

Moreover, Basquiat makes further references to the vanitas paintings of the Old Masters through his usage of the iconic skull motif: invoking the symbolism of memento mori lends these forms preternatural potency as they channel anguished psycho-spiritual states of being. As Hoffman writes, “These figures are unsettling, leaving the viewer with the feeling that they exist in another realm. Peering out into our space, they are oracles conveying a message from another dimension” (Fred Hoffman, The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York, 2017, p. 79).

The intensity and dynamism of Untitled (Indian Head) is largely indebted to Basquiat’s instinctive and idiosyncratic mastery of line. All the artist’s most celebrated works, whether ‘Heads’, ‘Warriors’ or text heavy masterpieces such as Hollywood Africans, are defined by his use of oilstick. Basquiat was always drawing, whether he was working on paper or canvas, and it is as a function of this that his works on paper became a cornerstone of his practice, privileged with a status far beyond the preparatory. As Hoffman again attests: “With the exception of Picasso, few acclaimed painters of the Twentieth Century invested the same time or energy to works on paper that is evidence in their painting. The search for pictorial solutions would have been fought out in front of the canvas. Yes, Twentieth Century painters drew and made masterful works in this medium, but drawing was always a secondary concern. For Basquiat, in contrast, there is often less of a distinction, in terms of intent, between working on paper and on canvas” (Op. cit., 2014, p. 33).

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Glenn, 1984. Private Collection. Art © 2025 The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat Licensed by Artestar

From 1983, as collage became one of his principal media, Xerox-ed drawings from his studio would become the substrate for his paintings. Indeed, the present work reappears as a Xerox in later masterpieces on canvas such as Glenn from 1984, illustrated on the cover of the artist’s recent Taschen monograph. Without the possibility of correction through overpainting, the ferocity of Basquiat’s works on paper fuse the aggressive urgency of Willem de Kooning’s Women of the 1950s with the graphic ciphers of Cy Twombly’s Ferragosto suite, as vividly demonstrated by Untitled (Indian Head).

Vibrating with immediacy, consummate draughtsmanship and undeniable self-reflection, Untitled (Indian Head) is a masterful example of Basquiat’s revered corpus of works on paper. Capturing the expressive urgency of his street art origins, the visual voltage of the present work offers explicit reference to Basquiat’s idiom of the warrior figure that embodies the young artist’s fierce ascent to the heights of critical and commercial acclaim. With impassioned, almost compulsive vigour, the frenzied streaks of colour achieve a remarkably heightened power – with the present work, Basquiat delivers a fusion of internal and external sensory experiences with the electrifying force of a live wire.