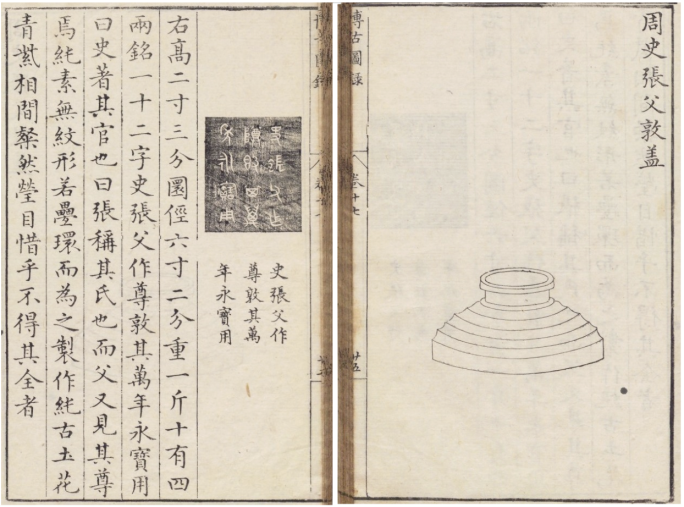

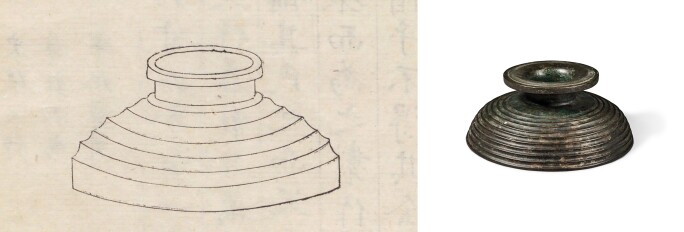

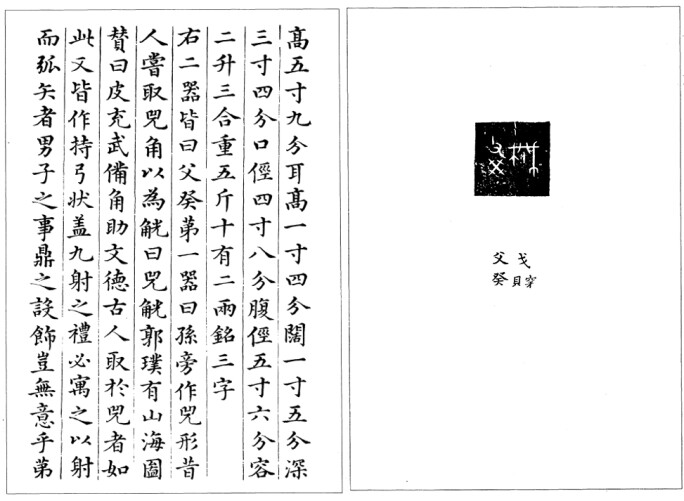

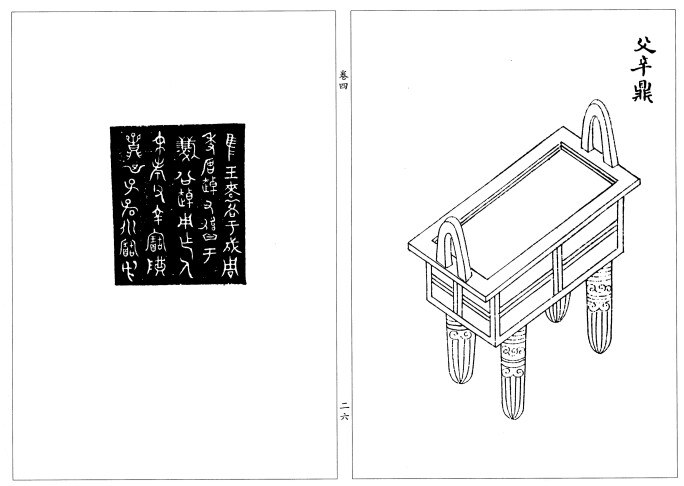

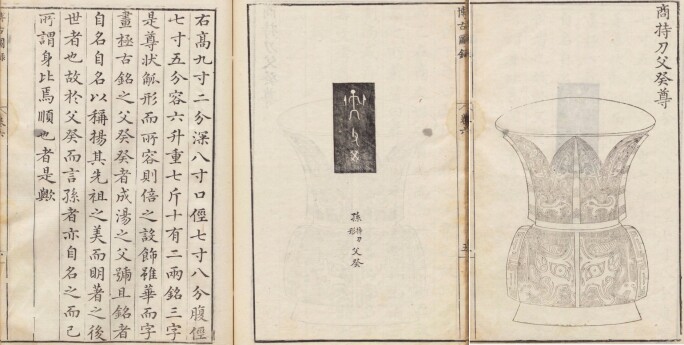

The form and the inscription of the present cover closely match the Shi Zhang Fu dui cover illustrated in Xuanhe bogu tulu [Illustrated catalogue of antique treasures from the Xuanhe hall], Boruzhai chongxiu edition, Wanli 16th year (1588), vol. 17, pp 25-26 (fig. 1). The two inscriptions have some minor discrepancies in the details of a few characters, as can be expected, since the book illustration is a woodblock print instead of a rubbing that is directly taken from the piece. It is also noticeable that the measurements of the present cover is slightly inconsistent with the records from the book. This inconsistency can also be seen on another example, the Cheng Fu Gui ding, where the current published diameter does not match the record from the Xuanhe bogu tulu. The Cheng Fu Gui ding is now in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and illustrated in Wu Zhenfeng, Shangzhou qingtongqi mingwen ji tuxiang jicheng [Compendium of inscriptions and images of bronzes from the Shang and Zhou dynasties], vol. 2, Shanghai, 2012, no. 00924.

Commissioned by the Emperor Huizong of Song (r. 1100-1126), Xuanhe bogu tulu is the first systematic catalogue of archaic bronzes from an imperial collection in China's history. Highly influential, the book has been referenced frequently by scholars. If the present cover is indeed the same one from this publication, it also appears in the following literature:

Wang Qiu, Xiaotang jigulu [Collection of antiquities from the Xiaotang], Song dynasty, vol. 2, p. 61.

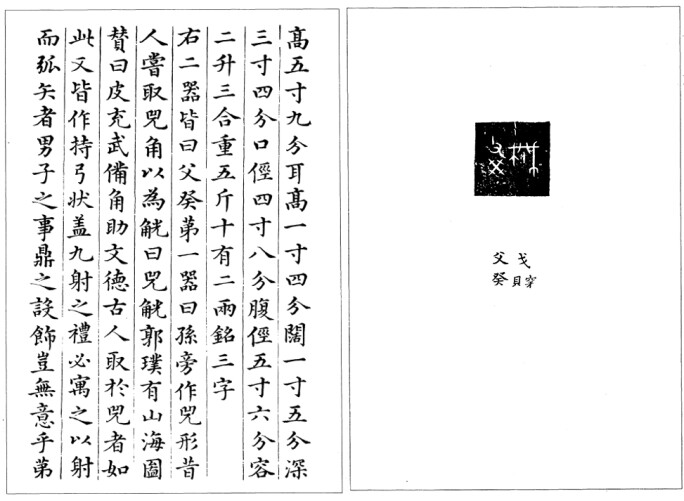

Xue Shanggong, Lidai zhongding yiqi kuanzhi fatie [Rubbings of the inscriptions from the archaic bronzes of the past dynasties], 1935, p. 121.

The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed., Yinzhou jinwen jichengshiwen [Interpretations of the compendium of Yin and Zhou bronze inscriptions], vol. 3, Hong Kong, 2001, no. 3789.

The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed., Yinzhou jinwen jicheng [Compendium of Yin and Zhou bronze inscriptions], Beijing, 2007, no. 03789.

Wu Zhenfeng, Shangzhou qingtongqi mingwen ji tuxiang jicheng [Compendium of inscriptions and images of bronzes from the Shang and Zhou dynasties], vol. 9, Shanghai, 2012, no. 04667.

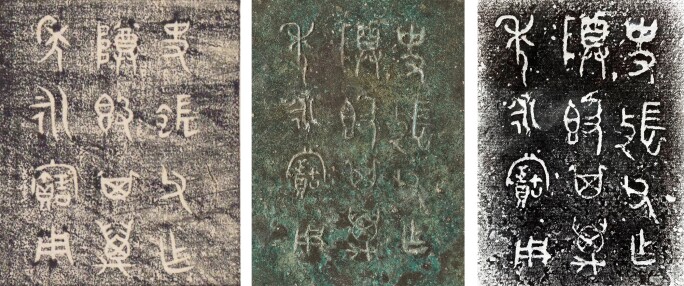

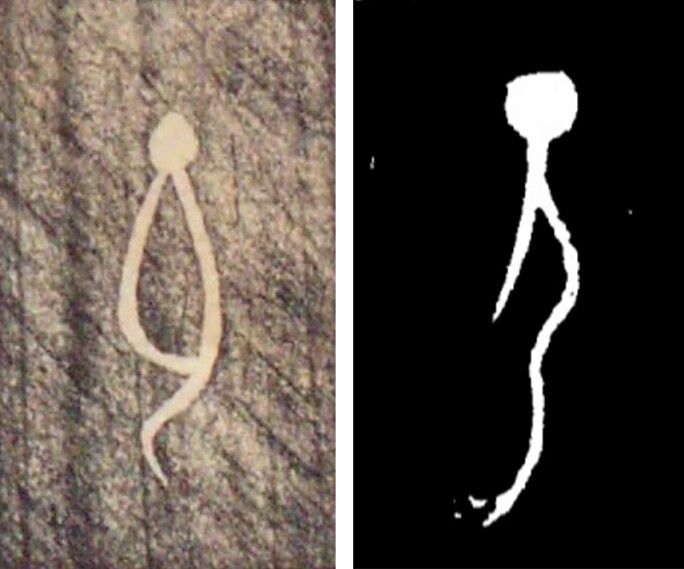

Interestingly, there have been different interpretations of the the second character in the inscription. The Xuanhe bogu tulu records it as zhang 張, with 弓 being the left radical. The more modern publications identify it as chang 立長, with 立 as the left radical. This is probably caused by the slight variation of this character in the different versions of the Xuanhe bogu tulu. The original Xuanhe bogu tulu from the Song dynasty does not appear to be preserved. The only available versions now are later reprints of the Song edition, and there are usually some discrepancies amongst the different versions. A closer examination of this particular character on the present cover, however, reveals the left radical, although closely resembling both 弓 and 立, is actually 攴/攵. It should then read 攴長/攵長, which does not appear to be a previously recognized character.

Emperor Huizong’s Bronze?

No collection of Chinese art has ever come close to that formed by the emperors. Finding a work that can be traced to an imperial collection is the holy grail of Chinese art. Now, in the upcoming Wou sale (A Journey Through China’s History. The Dr Wou Kiuan Collection Part 1 | 22 March 2022) in New York is an inscribed bronze (lot 1) that can possibly be the same one treasured by the Emperor Huizong (r. 1100-1126) of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) and recorded in the imperial collection of the Song court.

The Wou cover and its inscription closely match a bronze cover illustrated in the renowned Northern Song dynasty imperial catalogue of the court bronze collection treasured in the XuanheHall 宣和殿, Xuanhe bogu tulu 宣和博古圖錄 [Illustrated catalogue of antique treasures from the Xuanhe hall] (vol. 17, pp 25-26), which was compiled under the direct order of the Emperor Huizong. The likelihood of another bronze cover with this same inscription being preserved without its vessel is extremely slim. Whilst challenging to prove definitively, this article explores why the Wou cover is likely the same one from the Xuanhe bogu tulu.

The possibility of the present bronze being the one from the Xuanhe bogu tulu has significant implications:

- The first ever surviving bronze from the Northern Song imperial collection appearing in the market.

- One of the only two surviving bronzes from the Northern Song imperial collection ever known today.

- A surviving relic from the genesis of jinshixue 金石學 (epigraphy) in the history of China.

- A historic rediscovery of a lost treasure that has not been seen for nearly a millennium.

- An academic breakthrough in unravelling the true name of the maker of this bronze.

Provenance

Collection of Zhao Ji (1082-1135), Emperor Huizong of Song (r. 1100-1126).

The Northern Song Court Collection, treasured in the Xuanhe Hall.

Collection of His Excellency Hugues Le Gallais (1896-1964).

Sotheby's London, 11th November 1958, lot 80.

Collection of Dr Wou Kiuan (1910-1997).

Wou Lien-Pai Museum, 1968-present, coll. no. E.6.4.

Literature

Song dynasty publications:

Wang Fu et al., Xuanhe bogu tulu [Illustrated catalogue of antique treasures from the Xuanhe hall], Daguan reign (1107-1110) to Xuanhe reign (1119-1125), vol. 17, pp 25-26.

Wang Qiu, Xiaotang jigulu [Collection of antiquities from the Xiaotang], Song dynasty, vol. 2, p. 61.

Xue Shanggong, Lidai zhongding yiqi kuanzhi fatie [Rubbings of the inscriptions from the archaic bronzes of the past dynasties], Southern Song dynasty, p. 121.

Modern publications:

The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed., Yinzhou jinwenjichengshiwen [Interpretations of the compendium of Yin and Zhou bronze inscriptions], vol. 3, Hong Kong, 2001, no. 3789.

The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed., Yinzhou jinwenjicheng [Compendium of Yin and Zhou bronze inscriptions], Beijing, 2007, no. 03789.

Wu Zhenfeng, Shangzhou qingtongqi mingwen ji tuxiang jicheng [Compendium of inscriptions and images of bronzes from the Shang and Zhou dynasties], vol. 9, Shanghai, 2012, no. 04667.

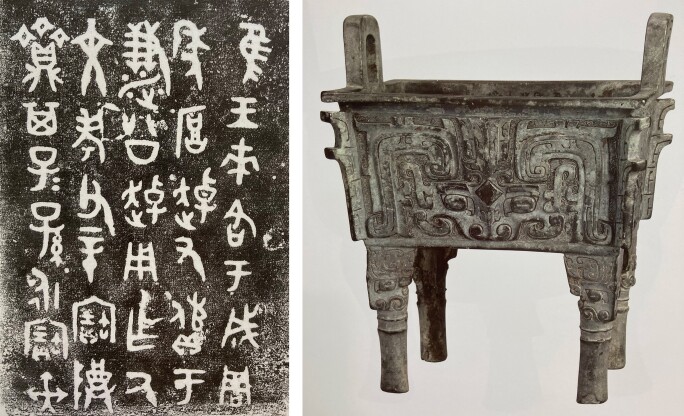

Both the form and inscription of the Wou cover display a remarkable resemblance to the one (referred as the Shi Zhang Fu dui cover) from the Xuanhe bogu tulu.

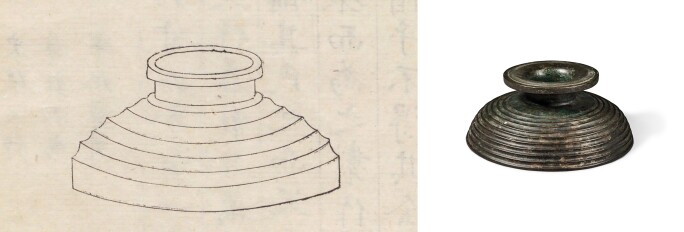

Comparison of the form

Right: Photo of the present lot

Comparison of the inscription

Center: Inscription of the present lot

Right: Rubbing of the inscription of the present lot

Attributing any bronze to the Xuanhe bogu tulu is not an easy task, due to inaccuracies in the details of the works illustrated and the fact that the original versions of the catalogue are no longer extant. Our knowledge of what was retained in the collection is based purely on later versions of the catalogue, which not only illustrate variations with the pieces themselves but also from edition to edition. This article explores some of these discrepancies and the likelihood that the Wou Kiuan cover is indeed the same one illustrated in the Xuanhe Bogu tulu.

Inscription of the Shi Zhang Fu dui cover in the different versions of the Xuanhe bogu tulu

Boruzhai edition, Wanli 16th year (1588)

Yu Daonan edition, Chongzhen bingzi year (1636), Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA

Yizhengtang edition, Qianlong 18th year (1753)

Siku quanshu edition, Qianlong 40th year (1781)

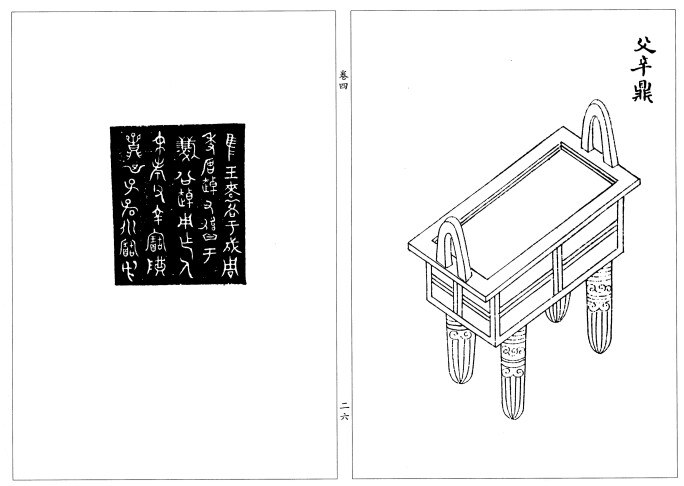

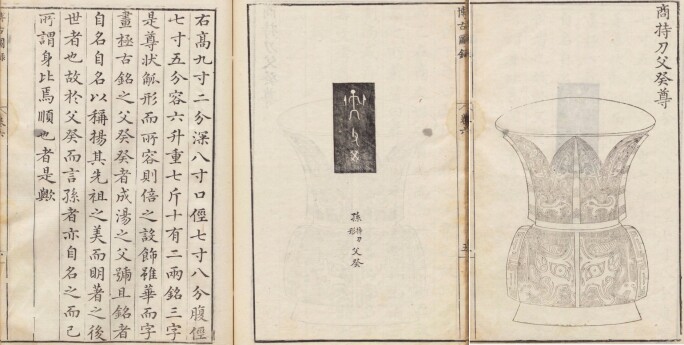

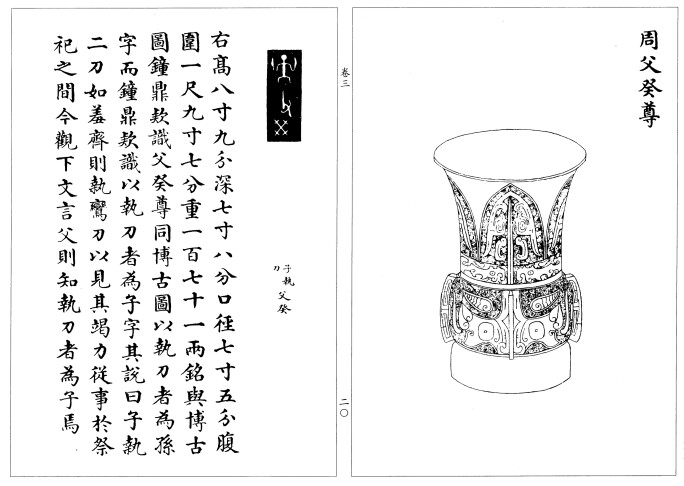

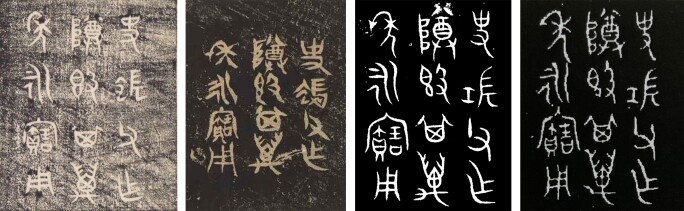

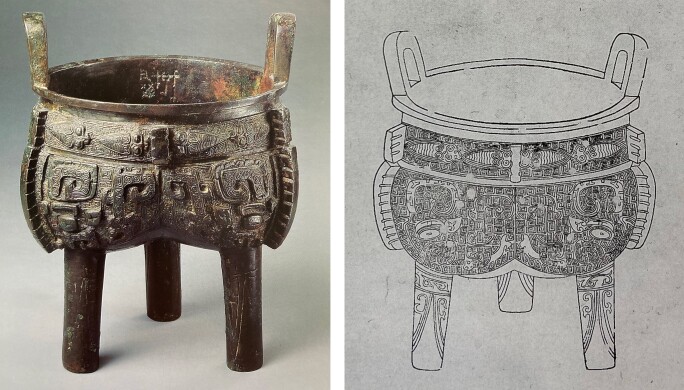

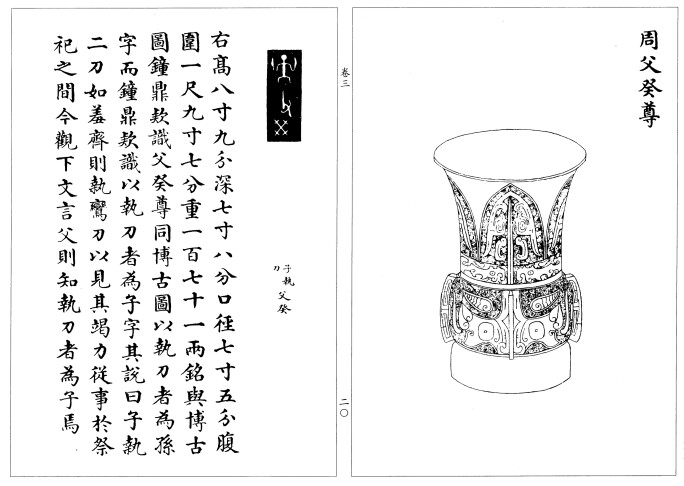

Such discrepancies can also be seen from another example, the Zhou Jie ding 周節鼎, published in the Xuanhe bogu tulu, vol. 3, p. 15, where the single pictogram of the bronze is inconsistent in the different versions of the book.

Right: Yizhengtang edition

In addition to the discrepancies between the different versions of the book, inaccuracies and errors are also prevalent in the Xuanhe bogu tulu, as well as in other related early bronze publications.

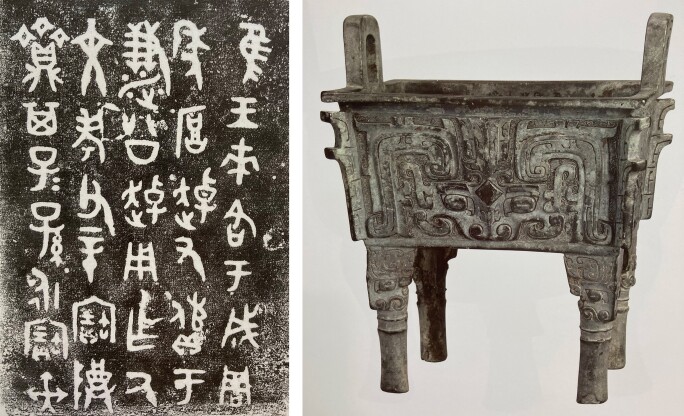

One of the bronzes, the Xiao Chen Ling ding 小臣夌鼎, from the Xuanhe bogu tulu (vol. 2, p. 14) has a rubbing of its inscription included in Liu Tizhi’s Xiaojiao Jingge jinwen taben [Rubbings of bronze inscriptions in the Xiaojiao Jingge], 1935, vol. 3, p. 17. A comparison of the rubbing and the woodblock print clearly demonstrates that the illustration from the Song catalogue is not a precise transcription of the actual bronze inscription. In addition to the numerous inaccuracies on the characters, there is even an extra ci 賜 mistakenly included in woodblock print.

The Cheng Fu Gui ding from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, is currently the only surviving bronze that has been widely accepted by scholars to be from the Northern Song court collection and the Xuanhe bogu tulu (vo. 1, p. 26). The ding was included in the exhibition Possessing the Past. Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1996, p. 221, pl. 96. In the exhibition catalogue, James C.Y. Watt acknowledges (p. 220) that there are usual minor misinterpretations of the details of the decoration in the illustrations from the Xuanhe bogu tulu (1752 edition). In addition to the minor inaccuracies in the design, the diameter of this ding (16.5 cm) was also incorrectly recorded in the Xuanhe bogu tulu by about 10% less.

Another example is a bronze zun (Fu Gui zun) included in both the Xuanhe bogu tulu (vol. 6, p. 5) and the Ningshou jiangu 寧壽鑑古 [Antiquity appraisal of Tranquil and Longevity] (vol. 3, p. 20), a bronze catalogue commissioned by the Qianlong emperor on the imperial collection of archaic bronzes housed in the Ning Shou Palace 寧壽宮. The same bronze was recorded in the two books with numerous discrepancies in the details of the design and inscription. Comparing the recorded weight of this zun from both books, there is also an approx. 35% difference in the numbers after the conversion.

Lastly, the Hou Chuo fang ding 厚趠方鼎 in the Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, is included in the exhibition Mirroring China’s Past. Emperors, Scholars, and their Bronzes, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 2018, cat. no. 58. This bronze was published in a Southern Song dynasty bronze catalogue by Lü Dalin 呂大臨, Xu Kaogutu 續考古圖 [Supplement to the illustrated investigation of antiquity] (vol. 4, p. 26), which features the line drawing of a completely different vessel. Dr. Wang Tao notes in the exhibition catalogue ‘as the book is known to contain errors, it could be a mismatch, or a case of the author drawing an imagined illustration without actually having seen the vessel’ (op. cit., 2018, p. 97).

問宋詰古:史□父簋蓋淺談

在中國藝術品收藏當中,要論極致大宗,莫過於帝王的皇家收藏。今見之古物,但凡出自皇家舊藏者,必定是備受珍視,價值無量。今季紐約蘇富比「藝萃流芳:吳權博士藏珍」專場(2022年3月22日)中所呈的一件青銅簋蓋(編號1),頗有研究意趣,其有可能為北宋宮廷之舊藏、宋徽宗之遺珍。

本次專場中的簋蓋與《宣和博古圖錄》中所錄的一件器蓋極為相似(卷17,頁25至26)。《宣和博古圖錄》可謂是中國歷史上皇家金石收藏圖錄的鼻祖,由宋徽宗敕撰,收錄了當時北宋皇室在宣和殿所珍藏的大量青銅器,是中國金石學上的一部具有里程碑意義的曠世鉅作。

本器若確為《宣和博古圖錄》所著之器,其價值將不可估量:

-目前市場上出現的唯一存世的北宋宮廷舊藏青銅器

-目前僅知的兩件存世的北宋宮廷舊藏青銅器之一

-見證中國金石學之始的歷史文化遺存

-沉寂近千年的金石遺珍再現於世

-對於研究金石學史有著重要的學術意義

來源

宋徽宗趙佶(1082-1135)收藏

北宋宮廷收藏,宣和殿藏珍

Hugues Le Gallais 閣下 (1896-1964) 收藏

倫敦蘇富比1958年11月11日,編號80

吳權博士 (1910-1997) 收藏

吳蓮伯博物院,1968年至今,編號E.6.4

著錄

宋代著錄

王黼等,《宣和博古圖錄》,宋大觀(1107-1110)至宣和(1119-1125)年間,卷17,頁25至26

王俅,《嘯堂集古錄》,宋,卷2,頁61

薛尚功,《歷代鐘鼎彝器款識法帖》,南宋,頁121

現代著錄

中國社會科學院考古研究所編,《殷周金文集成釋文》,卷3,香港,2001年,編號3789

中國社會科學院考古研究所編,《殷周金文集成》,北京,2007年,編號03789

吳鎮烽,《商周青銅器銘文暨圖像集成》,卷9,上海,2012年,編號04667

本品簋蓋無論從形制還是銘文均與《宣和博古圖錄》中的器蓋(書中舊名「史張父敦蓋」)極為相近。以下為《宣和博古圖錄》中刻版印刷與本器實物照片及拓片的對比。

器形

本品照片

銘文

本器銘文

本器銘文拓片

存世青銅器若想確定為《宣和博古圖錄》中所載之器絕非易事。蓋因此書年代久遠,此類早期書籍多有不甚嚴謹之處。更為關鍵的是此書宋代原版今已不可見,目前所見者均為後世刻版,其對於器物、銘文的記載及圖示與實物常有些許誤差,此早已被學術界所公認。有時同一器物在不同的版本當中亦可見到不小的差異。此文將通過一些示例,嘗試構架出一個合理的誤差範圍,從而為本簋蓋或為《宣和博古圖錄》中所載之器的可能性提供一些參考。

以下為不同版本的《宣和博古圖錄》中史張父敦蓋之銘文對比。通過對比,可見不同版本中的銘文在細節上都有明顯差別,因其均為刻版印刷而並非實物拓片。

于道南版,明崇禎丙子年(1636年),哈佛燕京圖書館藏,劍橋,麻省

亦政堂版,清乾隆十八年(1753年)

四庫全書版,清乾隆四十六年(1781年)

另見《宣和博古圖錄》中所著錄的周節鼎(卷3,頁15)。以下兩個版本中對於該器器銘的記錄更是大相徑庭。

亦政堂版

《宣和博古圖錄》中著錄的小臣夌鼎(卷2,頁14),同銘拓本可見於劉體智的《小校經閣金文拓本》(1935年,卷3,頁17),近時多認為同器。通過對比實物銘文拓本及《宣和博古圖錄》中的銘文刻版,我們不難發現後者並非是實物銘文的完全複製,其中多個銘字在細節上可見明顯差別,並且刻版當中還多出了一個「賜」字。

目前被學術界普遍接受的已知存世北宋宮廷舊藏、並著錄於《宣和博古圖錄》(卷1,頁26)的青銅器為台北國立故宮博物院所藏之成父癸鼎。此鼎曾見於重要展覽《Possessing the Past. Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei》,大都會藝術博物館,紐約,1996年,頁221,圖版96。展覽圖錄中,學者屈志仁在介紹此鼎時曾表示《宣和博古圖錄》(亦政堂版)所錄器物的紋飾與實物常常存在一些細小差別(頁220)。除紋飾上的差別之外,值得注意的是此鼎於《宣和博古圖錄》中所記的口徑亦有誤差,經過換算可知其比實物口徑(16.5公分)小了約10%左右。

成父癸鼎線描圖,《宣和博古圖錄》,亦政堂版

另可參考一尊例(父癸尊),同錄於《宣和博古圖錄》(卷6,頁5)及《寧壽鑑古》(卷3,頁20)。《寧壽鑑古》,「西清四鑑」之一,清乾隆帝敕撰,梁詩正、王傑等奉命編著,收錄乾隆御藏寧壽宮之吉金。同器錄於兩書之中,其器形、紋飾及銘文細節處明顯可見些許差異。另外,對比兩書所錄之器的重量,其數值在統一度量後亦相差了約35%左右。

除《宣和博古圖錄》之外,其他同時期金石著作當中也不乏差誤之處。上海博物館藏之厚趠方鼎,曾展於《吉金鑒古》,芝加哥藝術博物館,芝加哥,2018,編號58。此鼎錄於宋代的《續考古圖》(卷4,頁26),但書中的線描圖明顯錯錄。汪濤博士於展覽圖錄中記「眾所周知此書存在一些錯誤,此圖或為錯配,亦或作者在未見實物的情況下憑想像所繪」(前述出處,2018年,頁97)。