“If you believe that your art has a spiritual meaning and it helps you develop yourself, such art will truly be on the cutting edge of global culture.”

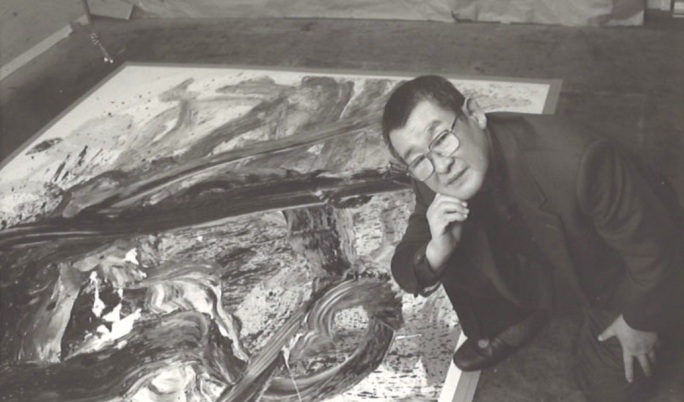

藝術家與本拍品合照

Hailing from Kazuo Shiraga’s post-Gutai period, Kosha from 1992 is a uniquely superlative piece executed in resplendent hues of radiant yellow and deep black, exhibiting one of the most charged, exuberant and exhilarating palettes within the artist’s highly acclaimed foot-painting lexicon. Created almost 40 years after the artist first swung across a canvas to kick and heave paint with his feet, Kosha remains as striking and powerful in its dynamic gesture as the artist’s earliest examples of abstract expression. Despite the thrilling visual tension of the two contrasting colours that are seemingly enthralled in a visceral struggle, Shiraga’s wide, loose strokes hold a natural elegance, reminiscent of the classical Japanese tradition of calligraphy. In his post-Gutai years, in the 1970s, Shiraga received intense training as a Buddhist monk, completing the training in 1974. The experience brought forth a significant evolution in his psyche as well as a heightened consciousness within his gestural art; emanating from Shiraga’s dexterous and dynamic action-based painting is a sense of transcendent wisdom enlightenment. The title Kosha refers to “yellow sand”, a meteorological phenomenon in Asia whereby high-speed surface winds and intense dust storms carry yellow sand from the deserts of Mongolia and Kazakhstan. As one of the few intensely electrifying yellow paintings Shiraga’s oeuvre, Kosha is a rare paradigm exhibiting the consummate choreography, centered balletic tension and sublime balance that communicate the artist’s spiritual mastery of his raw passions: in it we witness Shiraga raised from his angst, revelling in the authority of matter, body and spirit.

藝術家與本拍品合照

Born in 1924 in Aagasaki, Japan, Shiraga originally trained in Nihonga at the Kyoto City University of Arts. The artist soon turned to oil, creating markings or scratchings with his fingers; beginning with these early methods, Shiraga’s art form gradually abjured the brush and took its final form in his celebrated foot paintings. In the early 1950s, a period on par with Jackson Pollock’s action paintings, Shiraga shunned the orthodox artistic stance completely. Fastening a rope to the ceiling, the artist swung himself acrobatically across horizontally placed canvases, using his feet and body to cast, heave, kick and swirl thick slabs and layers of paint. Such uninhibited actions allowed the artist to immerse himself within his canvas as opposed to merely pouring or painting from above; by merging body with matter in a cathartic synthesis, Shiraga set himself apart from the mere gesturality of Western Abstract Expressionism and thrashed out an impassioned path of primal expression. Like no other artist before him, Shiraga’s performative abstractions were vehemently inspirited with movement—“not just the movement of his body […] but also the assertion of matter itself” (Ming Tiampo, “Not just beauty, but something horrible”, in Exh. Cat. Body and Matter: The Art of Kazuo Shiraga and Satoru Hoshino, New York 2015, pp. 21-22).

威廉·德庫寧,《女-48》,約1950年代

Concurrent to the development of his foot-painting technique, Shiraga’s career took flight in the late 1950s and 1960s as a result of iconic and internationally acclaimed performances. In his seminal 1955 Challenging Mud, Shiraga plunged himself into a vat of clay and sludge, engaging in a raw and vehement battle with the earth. Afterwards, fellow Gutai artist Akira Kanayama wrote that Shiraga arose from the mud “as if emerging from a bath, refreshed” (Akira Kanayama, “Shiraga Kazuo”, Gutai, no. 4, 1955, p. 9). Another pivotal performance was Shiraga’s 1957 Ultra-Modern Sanbasō. The 1957 “Gutai Art on the Stage” exhibition opened with Shiraga emerging alone on a lit stage, donning a theatrical red costume with a pointed hat and performing dramatic bodily movements. Accentuated by elongated wing-like sleeves, Shiraga’s arm actions created slashes of undulating color against the stage backdrop, constituting an homage to Japan’s oldest celebratory dance, Sanbasō ('divine dance'). As Alexandra Munroe notes, while Euro-American Happenings fused art with life as a critique of commoditized culture, Shiraga’s Ultra-Modern Sanbasō was an “affirmation of art in life after [the country’s] near annihilation of culture” (Alexandra M

unroe, “To Challenge the Mid-summer Sun”, in Japanese Art After 1945: Scream against the Sky, Guggenheim, 1994, p. 97).

These performances underscore the centrality of Shiraga’s gesturality within his oeuvre, which is grounded in the concept of shishitsu, meaning “innate characteristics and abilities”, which serves as the driving force behind the shaping of the self. Making art was a way for the legendary master to fully connect with his shishitsu - a means to connect with himself, through himself. Such an understanding is crucial to a full appreciation of Shiraga’s body-based oeuvre: while Klein also utilized the body as paintbrush in his Anthropometries works half a half a decade later, Shiraga’s art utilized his irreducible corporeality to battle with and awaken the raw vitality of matter itself. Such a paradigm epitomized the mission of the post-war Gutai artists who, literally uniting ‘instrument’ (gu) with ‘body’ (tai), rose fearlessly from the rubble of post-Hiroshima Japan to advocate a reinvigorating philosophy of ‘concreteness’ in their war-torn country. Shiraga once said that his art “needs not just beauty, but something horrible” (Kazuo Shiraga, interview with Ming Tiampo, Ashiya, Japan, 1998); by engaging with, and transcending, violence, Shiraga was able to “wrestl[e] with the demons that haunted him and his generation, at the same time opening the possibility of hope for the years ahead” (Body and Matter: The Art of Kazuo Shiraga and Satoru Hoshino, New York, 2015, p. 23). In his post-Gutai years, Shiraga not only received training in Buddhism but also re-engaged with traditional ink and brush calligraphy to complement his technique and breadth of style. Such a re-embracing of his oriental roots lends Shiraga’s feet-strokes the essence and soul of masterful ink brushwork, gracing his by-then universally acclaimed canvases with transcendent traces of his Eastern origins.

「如果你相信自己的藝術有精神意義,而且有助你成長,這樣的藝術才真正站在全球文化的浪尖上。」

《Kosha》作於1992年,是白髮一雄後具體時期獨特而優秀的作品。此作以鮮黃色和深黑色為主調,光彩照人,用色風格展現激烈狂亂的力量,洋溢熱情且令人興奮,實屬藝術家廣受讚譽的足畫系列當中最出色的作品之一。藝術家以足繪畫時會懸吊在畫布上方,來回擺盪,或踢踹、或踩踏顏料。在他初次創作足畫近40年後,他創作了《Kosha》,而此作貫徹他早期的抽象表現風格,其動勢仍然強而有力,震懾人心。畫中兩種色彩對比鮮明,似乎陷入交纏搏鬥,形成強烈的視覺張力,儘管如此,白髮一雄寬闊、鬆散的筆觸卻又散發著自然的優雅氣息,讓人聯想到日本古典書法傳統。在白髮一雄的後具體時期,亦即1970年代,他接受了嚴格的佛教僧侶培訓,直至1974年方完成訓練。這次經歷使他的心理出現重大的變化,並且提升了其動勢藝術所蘊含的意識;白髮一雄靈巧而極富動感的動態繪畫乃源自於一種超凡智慧的啟迪。本作題為《Kosha》,意為「黃沙」,即亞洲的一個天氣現象,其發生之時,高速的地面風和沙塵暴猛然捲起蒙古和哈薩克斯坦沙漠之黃沙。作為白髮一雄作品中極少數的黃色畫作之一,《Kosha》堪作難得一見的範例——從構圖可見圓滿的編舞,中央呈現芭蕾舞步姿的張力和絕妙的平衡,傳遞出藝術家精神上對於原始激情的掌控:我們可在作品中見證白髮一雄從焦慮煩憂中解脫,繼而陶醉於對物質、身體和精神的掌握之中。

1924年,白髮一雄生於日本長崎市。最初,他學習傳統日本畫(Nihonga),後轉向油畫,以手指或指甲蘸取顏料創作,從那時起,他便摒棄畫筆,將自己的藝術形式昇華到一個新層次,最終演化成著名的足繪作品。1950年代初,亦是傑克森·波拉克發展其行動繪畫的重要時期,白髮一雄終於摒棄傳統藝術規限,將畫布平鋪於地面上,在天花板上固定繩子,自己則執繩盪於空中,以足蘸濃稠的顏料,層層地踢抹、摔摜於畫布上。畫家並不滿足於把顏料潑或畫在畫布表面,而是藉著這種大膽狂放的創作方式,全身心投入到作品中去,將身體與物質融為一體,流暢迅疾、勢如流星。如此一來,他將自己與西方抽象表現主義的動勢繪畫區分開來,為當代藝術界闖開一片新天地。這位具體派畫家在當年青春正盛之時破天荒以足繪畫,開闢了一種狂野原始的藝術表達方式,其抽象藝術表演充滿激烈狂亂的動作——「不只是身體的動作…… 物質亦隨之騷動起來。」(蔡宇鳴撰,〈Not just beauty, but something horrible〉,《身體與物質:白髮一雄與星野曉的藝術》展覽圖錄,紐約, 2015年,頁21-22)

另一位具體派藝術家金山明寫道,當白髮一雄從泥土中站起身來,彷彿剛剛沐浴過一般,煥然一新。(金山明撰,〈白髮一雄〉,《具體》,第4期,1955年,頁9)繼《挑戰泥土》後,白髮一雄在1957年進行另一場前衛藝術表演《超現代三番叟》。在1957年「具體藝術舞台」展覽的開場上,白髮一雄在亮著燈的舞台上獨自現身,套上紅色戲服、頭戴尖帽,劇烈地舞動身軀。如巨翼般的兩袖在舞台背幕前掀起一陣色彩的波浪,模仿並向日本最古老的祭典舞蹈「三番叟」致意。本作用色狂艷奔放,與藝術家標誌性的表演的狂歡色彩互相呼應。孟璐(Alexandra Munroe)認為,歐美的「偶發藝術」將藝術與生活合而為一,以批判當前的商品文化;但白髮一雄的《超現代三番叟》卻「在(其國家的)文化近乎消滅之後,肯定生活中的藝術。(孟璐撰,〈挑戰仲夏驕陽〉,《1945年後的日本藝術:向天空吶喊》,古根海姆,1994年,頁97)

這些表演強調白髮一雄全部作品中的中心主題,即以「個人本質」(shishitsu)的概念為基礎,是一種自我塑造的驅動力。藝術創作就是白髮一雄與自己的「個人本質」完全聯繫的方式——一種通過自己與自己聯繫的方式。這個概念對於理解白髮一雄以身體為創作工具的做法可謂至為關鍵。伊夫·克萊因也在《身體繪畫》系列裡以人體代替畫筆;白髮一雄則用自己純粹的身體力量對抗、喚醒物質內在的生命力。日本戰後具體派的理念在他的作品中被前所未有地實現並達到高峰;他將工具(「具」)與身體(「體」)結合,無懼地走出日本原爆後的頹垣廢墟,他要讓因戰爭而撕裂的日本社會重新振作,高呼一種「具體」的新生哲學;他曾言其藝術「不只需要美,更要可怕」(白髮一雄,與蔡宇鳴對談,1998年)。 白髮一雄通過與暴力交戰,並戰勝它,得以「與纏繞著他與那一代人的夢魘鬥爭,並打開了未來的希望之路。」(《身體與物質:白髮一雄與星野曉的藝術》展覽圖錄,紐約, 2015年,頁23)

離開具體藝術協會後,白髮一雄不僅學佛,也重新開始學習傳統水墨書法,以拓展藝術風格和技巧。這段回歸本源的經歷,為他那標誌性的足繪藝術增添了幾分水墨神韻,點明了他的東方本源。本畫構圖精微熟練,而且取名自一個與佛教傳播息息相關的中亞民族。畫面旋舞的張力集結在中央而得到平衡,儼然宣告藝術家精神上的提升、對喜怒哀樂的自如釋然——他擺脫了焦慮與不安,沉醉於身體、繪畫與精神當中。