“Plastic Tubs pivots on the delectability of the shiny plastic vessels; the painting is attractive in part because the colorful goods are tantalizing, even in their incompletion.”

Executed in 1964, Sigmar Polke’s vibrant painting Plastik-Wannen [Plastic Tubs] has become a seminal icon of the artist’s early works from the 1960s. Exhibited extensively between 1971 and 2015 in shows across Germany, America, and the UK, this work has garnered great critical attention as an example of Polke’s early foray into the language of advertising. The painting is one of a handful of oil paintings Polke made in the 1960s, depicting banal, everyday objects—culled from newspapers and magazines—that are nevertheless rendered as glossy and alluring objects of desire. With its Pop inspired execution, vivid palette, tonal shading and contouring, strikingly juxtaposed against deliberately unfinished elements, Polke’s depiction of a series of plastic tubs offers a tongue-in-cheek contemplation of both the seductive façade and empty promises of a consumer driven society. As curator Lanka Tattersall has stated, “Plastic Tubs pivots on the delectability of the shiny plastic vessels; the painting is attractive in part because the colorful goods are tantalizing, even in their incompletion.” (Lanka Tattersall, ‘Eight Days a Week’ in: Exh. Cat., New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Alibis: Sigmar Polke, 1963-2010, 2014, p. 101) Notably, the present work, alongside three of the other Polke paintings in The Macklowe Collection, was previously held in the collection of Charles Saatchi in London, who was one of Polke’s first major patrons and owned a number of the artist's most important paintings.

If Pop art probed the saturation of consumer culture within modern society, post-World War II Germany presented the ideal case-study. A nation quite literally divided in two, the Eastern block was shielded from all capitalist media while West Germany struggled toward economic revitalization following wartime devastation. At just 12 years of age, Polke surreptitiously crossed with his family from East Germany to the West: his experiences of life on either side of the Iron Curtain, each characterized by staunchly oppositional dogmas, were to profoundly impact his artistic practice. Born in 1941, Polke grew up within a climate of severe political instability, devastating poverty, and state repression. His architect father was conscripted to build covert military facilities by the Nazis, the purpose of which he never revealed. The seventh of eight children, Polke and his family fled from the Polish region of Silesia to Soviet-occupied Thuringia in 1945 during the German expulsion following World War II. Eight years later, the Polkes escaped Communism under the GDR, settling in Düsseldorf by way of Berlin.

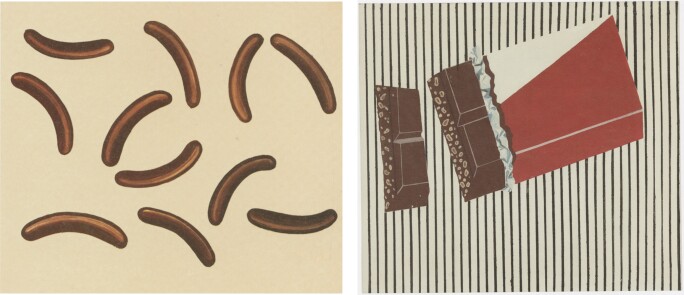

As a teenager growing up in West Germany, the artist bore captive witness to the proliferation of newspapers and magazines rife with images depicting a prosperous, modern nation, and experienced, firsthand, the manipulative power of propaganda and the media. During the late 1950s and early ’60s, West Germany promoted what was coined the Wirstchaftwunder—the ‘economic miracle’ supporting the accelerated reconstruction of the nation’s economy—through the printed press, a cheap and infinitely reproducible vehicle for collective nation-building. Commercial printing became the most inconspicuously powerful socializing force shaping this ideological reformation. Reconstruction in West Germany after the fall of the Third Reich, however, was not as prosperous as the media purported. Two years after the war ended, food production stalled at only 51% of what it had been in 1938. While Polke was painting advertisements of nougat-centered chocolate bars as a reflection of the alleged lifestyle of increased affluence and consumption, potatoes still remained a dietary necessity for the majority of the German population. Thus, Polke was highly critical of the mass media imagery adopted by the country as its primary instrument for socioeconomic and political reprogramming.

Polke’s early works of the 1960s galvanized not only West Germany, but the entire landscape of post-war painting. Capturing the social acuity that Lichtenstein and Warhol brought to their renderings of everyday commodity culture, Polke infused his own practice with the weight of Germany’s postwar, guilt-ridden socioeconomic state. Appropriating the pictorial shorthand of commercial printing, Polke illustrated the consumer provinciality of West Germany in contrast to the dazzling allure and seductive elegance of his American contemporaries. Indeed, the candies, cakes, chocolates, and sausages that dominate Polke’s earliest paintings were in reality not easily obtainable in the Germany of the 1950s and 1960s. In depicting these luxury items, Polke uncovers the experience of living with such imagery, without having the means actually to access the commodities themselves. In Plastik-Wannen, Polke at once draws upon this sense of the unattainable, as expressed through the commercialization of products, whilst shattering the illusion by leaving the top segment of the painting deliberately and jarringly incomplete. In embracing the American preoccupation with commercial imagery whilst subverting the attraction with an inflected irony concerning the political agenda at the heart of such representations, Polke at once captures the sensation of desire and concomitant absence of fulfilment characteristic to the consumer society of West Germany. As Kathy Halbreich described, “Polke’s love-hate relationship with the political and economic power of the United States began here, with an abundance both unattainable and unwanted. Even as the flood of consumer products in the 1950s operated like a narcotic, dulling memories of recent need and longing, there was a chill in the air. Increased prosperity had its own cost, and Germany, like postwar Japan, experienced what Ian Buruma has described as ‘bourgeois conformism… with its worship of the television set, the washing machine, and the refrigerator (‘The Three Sacred Treasures’), its slavish imitation of American culture, its monomaniacal focus on business, and the stuffy hierarchies of the academic and artistic establishments.’” (Kathy Halbreich, ‘Alibis: An Introduction’, Ibid., p. 77)

RIGHT: SCHOKOLADENBILD, 1964. GLENSTONE, POTOMAC, MARYLAND

BOTH © 2022 The Estate of Sigmar Polke, Cologne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In works such as Plastik-Wannen, Polke potently adopts the pictorial style of advertising in order to depict the consumer society’s highly prized objects of desire, harnessing the vivid block colors and simplified forms used to promote such aspirational, unattainable images. Polke clearly understood how differently affecting this iconography was to a German reality recently freed from the shackles of oppressive socialism, in stark contrast to the functional impression of these advertising ideals to an American public. The artist’s keen unravelling of the disjuncture inherent in the connections between consumerism and repression informed his best pictures, most notably Plastik-Wannen. Simultaneously appropriating and disrupting the language of advertising, Polke produces an arresting and timeless image that is at once reductive, seductive and resolutely quotidian.