"You paint 100 chimpanzees and they still call you a guerrilla artist.”

Image/Artwork: © Banksy 2021

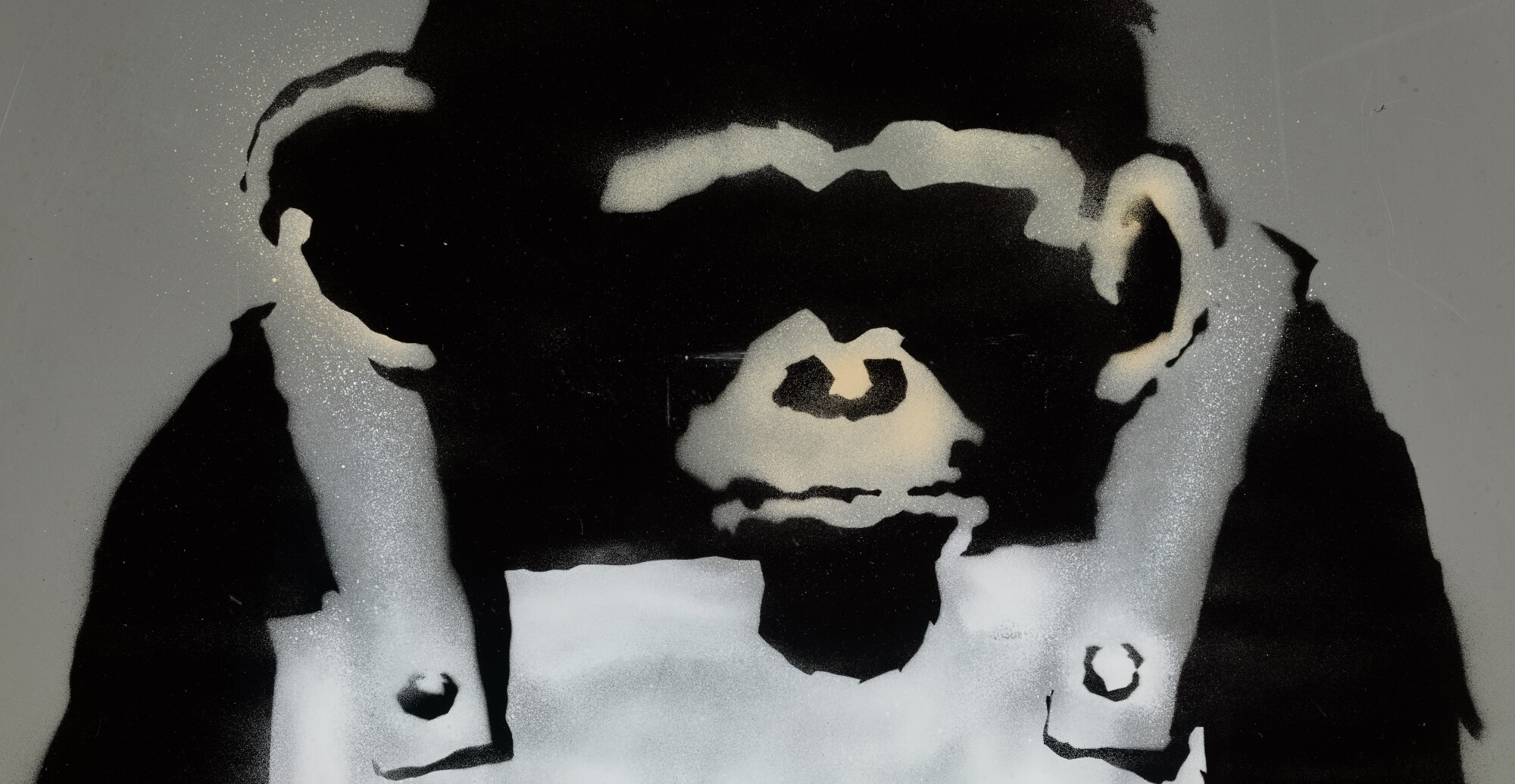

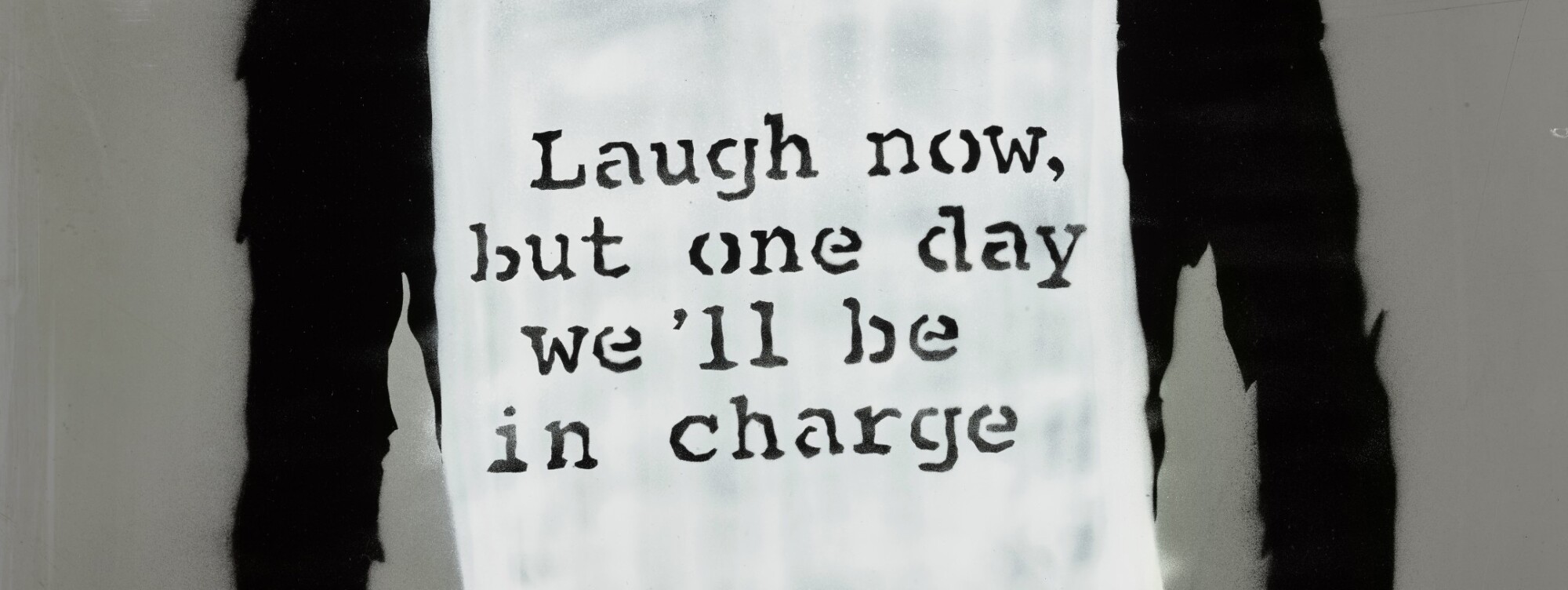

Alongside the rat, Flower Thrower, and Girl with Balloon, the sandwich-board-wearing Laugh Now chimp is one of Banksy's central icons. The present work represents its apotheosis: with a full and detailed stencil composition articulated in a wider than usual range of spray-painted tones and on large scale also unusual for this motif, this unique painting on metal is an exceptional and quintessential example of Banksy’s work. This piece also possesses an unparalleled exhibition history having made its debut in the artist’s paradigm-shifting LA exhibition, Barely Legal: a street-art take-over warehouse extravaganza that is today considered the most important exhibition of the artist’s career to date. In preparation for Barely Legal, Banksy created a concise series of works on identical sheets of metal shelving. These entailed a compendium of the most popular and significant motifs of his career so far, including the Kissing Coppers, Bomb Hugger, and the present work – Laugh Now. In its raw immediacy and use of a found-industrial material as the painting’s ground we are reminded of the central paradoxes of Banksy’s career: at once poignant and pun-fuelled, he toes the line between vandal and creator, creating works of acerbic impact that advocate for the marginalised in society. Simultaneously at the centre of the art world and entirely apart from it, he is, at once, the most famous artist working today and an anonymous outsider. In his own words: “You paint 100 chimpanzees and they still call you a guerrilla artist” (Banksy cited in: Caroline Goldstein, ‘Banksy Is Giving His Painting of Chimpanzees Overrunning Parliament a Special Appearance to Mark “Brexit Day”’, Artnet News, 29 March 2019, online). As tremendously deployed in Laugh Now, Banksy is a master of surprising juxtapositions; using humour and biting satire, his work undercuts the elite to elevate the proletarian and shed light on the great issues of our time.

The chimpanzee or monkey is one of the most powerful motifs in Banksy’s arsenal. The present motif first made an appearance in 2001 in one of Banksy's first 'exhibitions', a showing of work staged under a railway bridge on Rivington Street in Shoreditch. Slump-shouldered and forlorn, Banksy’s chimp offers viewers the following maxim: ‘Laugh now, but one day we’ll be in charge’. Cartoon comedy quickly turns into biting social critique in Banksy’s hands as he invokes Charles Darwin’s theory of man’s evolution. Banksy’s tabard-toting ‘monkey’ thus takes on the arrogance of mankind. In homage to this iconic motif, Banksy would go on to create one of his most ambitious works: the grand-scaled history painting, Devolved Parliament. Depicting the house of commons run amok with chimpanzees, this painting offers both a stark realisation of Laugh Now's premonition and a comment on our current political situation. Considering Banksy’s practice, author Patrick Potter has stated, “These images can be really arresting at their best. They’ve evolved from the kind of cartoonish carnival of Banksy’s animal army to controlled irony, designed to reveal the foolishness hidden in plain view in our society’s values” (Patrick Potter, Banksy: You are an acceptable level of threat and if you were not you would know about it, Durham 2012, n.p.).

Private Collection

Artwork: © Banksy 2021

By the early 2000s Banksy had earned a cult following for his subversive stencilled street pieces that would appear overnight on vacant walls around Bristol, London and increasingly further afield. Serving pithy social commentary via lightning-quick dark-humoured punchlines in public places as controversial as the Segregation Wall in Palestine, Banksy became immensely popular with a broad cultural base. By the decade’s mid-point, his work began to veer increasingly towards more traditional artworld territories. Losing none of his satirical bent, however, his foray into the artworld establishment was to remain just as dissident and subversive, operating on paradoxical levels that further served to heighten the underlying political and satirical impetus of his work.

Banksy Icons at Auction

Via the handful of exhibition projects that comprise Banksy’s back catalogue of solo shows – beginning in 2003 with Turf-War, then the 2005 Crude Oils, Barely Legal in 2006, his takeover of the Bristol Museum in 2009, and the pop-up ‘bemusement park’ Dismaland in 2015 – Banksy has debuted paintings and sculptures on platforms that utterly defy the traditional artist/gallery model. From vandalised warehouses and rat-infested gallery spaces, to an overrun museum and an apocalyptic theme park, these immersive art-happenings propelled Banksy’s name to greater heights of popularity and notoriety. Of these, it was Barely Legal, the artist’s full-scale Stateside debut of 2006, that truly cemented his status far beyond that of Bristolian graffiti-tagger.

Image: © James Pfaff

Artwork: © Banksy 2021

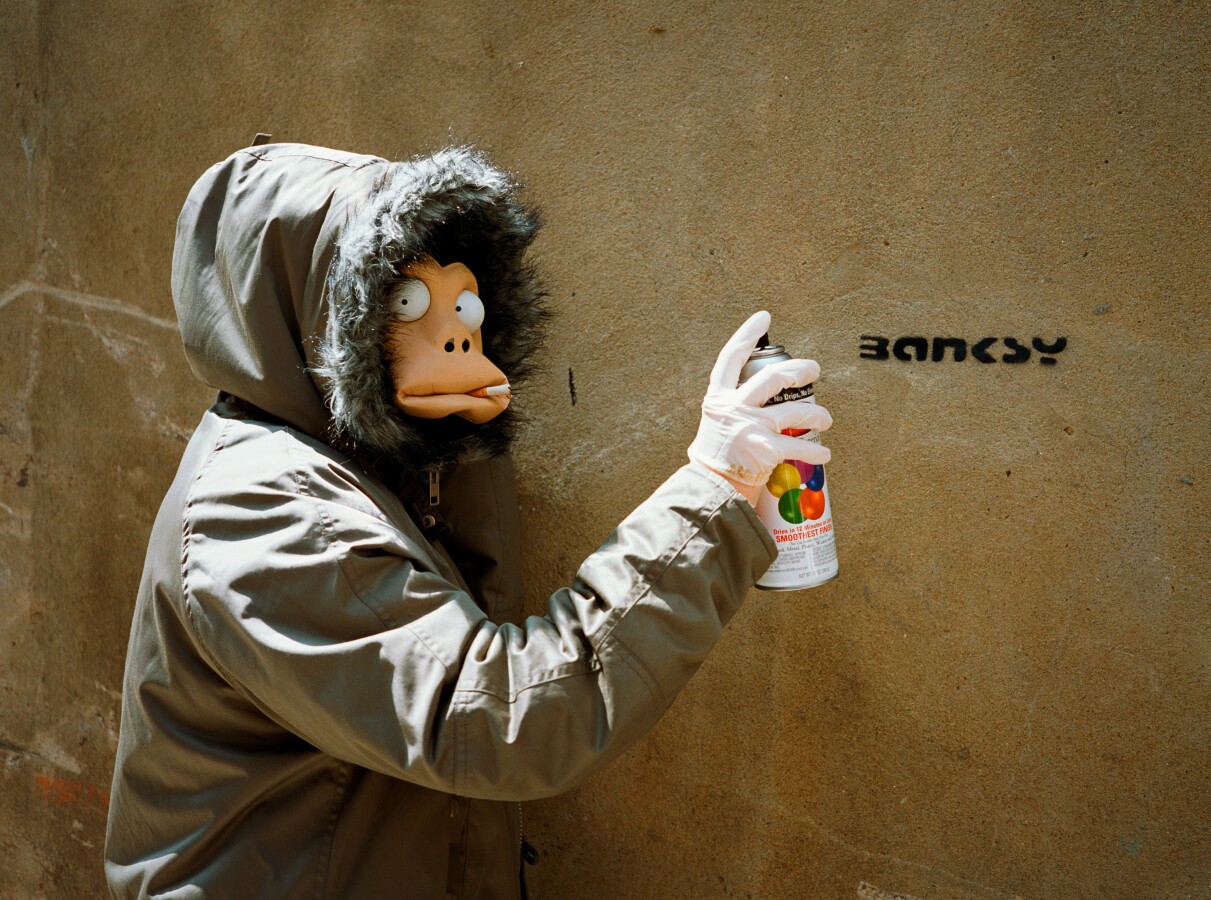

LA is a city of extremes: home of Hollywood and the silver-screen it also boasts one of the highest rates of violent crime and homelessness in the United States. It is this very paradox that offered the perfect setting for Banksy’s caustic anti-establishment art event. Three years before, Banksy had transformed a rundown warehouse off the Kingsland Road in Dalston into his first major exhibition, Turf War, in which graffiti-tagged livestock, a vandalised police van and large-scale stencil pieces turned a disused industrial space into an ostentatious street art spectacle. Taking inspiration from this breakout event, Banksy ramped it up for his first large-scale show in the United States. Like Turf-War, the location of Barely Legal was kept a secret until just hours before it opened, having been promoted all over the city using a poster in which Banksy represented himself as a pregnant Demi Moore in a monkey mask. Belying the superficial camp parody and provocation of the event and its works, however, the paradoxical social consciousness at the heart of this show achieved new heights of conceptual meaning and, also, notoriety for the anonymous artist.

Artwork: © Banksy 2021

Barely Legal took place in Skid Row – an impoverished part of Downtown LA that contains one of the US’s largest homeless populations. Over three days in September, the exhibition was attended by hordes of people. Reportedly the entrance queue at one point stretched a mile-long and the opening night even attracted the most glamorous and celebrated among the A-list glitterati: Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Jude Law, Dennis Hopper and Cameron Diaz were said to have attended. The striking juxtaposition of Hollywood glamour and street art on Skid Row brilliantly underscores how Banksy consistently calls out radically asymmetrical power relations in his work. To this end, at the very centre of the exhibition Banksy devised and staged an installation piece involving a live elephant. Fenced-off into a living room area complete with a chintzy-sofa, Turkish rug, crystal chandelier, and red and gold flocked wallpaper hung with gilt-framed vandalised oil paintings, was a large thirty-seven-year-old Indian elephant, painted (with non-toxic face paint) to match the room’s ersatz bourgeois interior. As a punchline to this installation, exhibition attendants handed out a card with the following text: “There’s an elephant in the room. There’s a problem that we never talk about. The fact is life isn’t getting any fairer. 1.7 billion people have no access to clean drinking water. 20 billion people live below the poverty line. Every day hundreds of people are made to feel physically sick by morons at art shows telling them how bad the world is but never actually doing something about it. Anybody want a free glass of wine?” (Banksy, Los Angeles, 2006).

“Central to Banksy’s work is an attempt to re-frame global issues through the use of irony, and ironic inversion. His work interrupts mainstream narratives of global ethics, of an unfair world that needs reform, by juxtaposing familiar icons of western capitalism… Banksy may not provide ready solutions to some of the problems he identifies, but he certainly provides credible pointers as to the kinds of power structures and hypocrisy that global ethical agendas must contend with.”

Here lies the central paradox of Banksy’s work: it operates both inside and outside of the establishment, it skirts the boundary between good and bad taste, and courts mass appeal whilst commenting on potentially marginalising political and cultural issues. Utilising a mainstream comedic framework that employs an ironic critical distance, Banksy is able to effectively approach a complicated and multifaceted discussion that prompts us to rethink our assumptions and, perhaps, even resist them. To quote James Brassett who focuses on the work of Banksy in his analysis of ‘British Irony and Global Justice’: “Central to Banksy’s work is an attempt to re-frame global issues through the use of irony, and ironic inversion. His work interrupts mainstream narratives of global ethics, of an unfair world that needs reform, by juxtaposing familiar icons of western capitalism (for example Disney, Ronald McDonald) with icons of western imperialism (for example bombed villagers in Vietnam)… Banksy may not provide ready solutions to some of the problems he identifies, but he certainly provides credible pointers as to the kinds of power structures and hypocrisy that global ethical agendas must contend with” (James Brassett, ‘British Irony, Global Justice: A Pragmatic Reading of Chris Brown, Banksy and Ricky Gervais’, Review of International Studies, Vol. 35, No. 1, January 2009, pp. 232-33). As typically at stake in works such as Laugh Now, despite the cynical puns, witty punchlines, and an espousal of anti-taste and shock tactics, there is a sense of ambiguity that more often than not authentically challenges issues concerning representation and power structures in contemporary life. This is what makes his work so fascinating, appealing, and ultimately so enduring.