Lot41 L24006 CY6Y2

-

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story -

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's -

Geek WeekA 54-Pound Martian Meteorite Just Landed at Sotheby's — But How Did It Get Here?

Geek WeekA 54-Pound Martian Meteorite Just Landed at Sotheby's — But How Did It Get Here?

“In landscapes I sometimes found a way to reconcile my idea of pure and divided colours…”

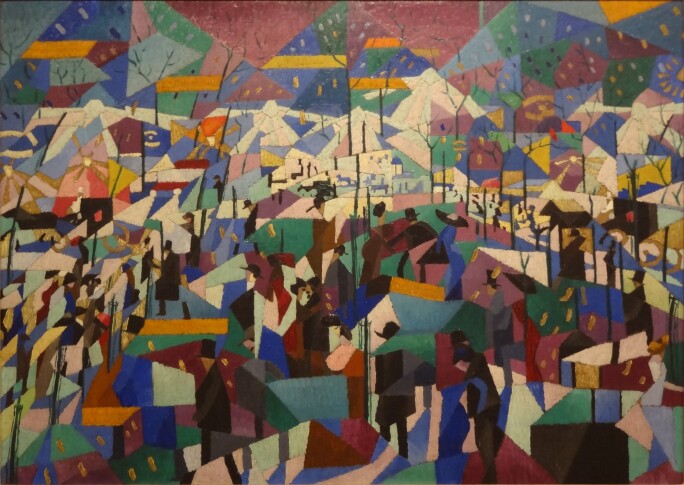

Conceived on an impressive scale at nearly two metres in length, Paesaggio di Civray is among the very best examples of Severini’s early work and the experiments with a Post-Impressionist idiom that would ultimately lead him to Futurism.

The young Severini arrived in Paris in October 1906, penniless and unable to speak French. He described wanting to “rejoice in the unforgettably grand surprise it offered” (Exh. Cat., London, Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, Gino Severini. From Futurism to Classicism, 1999-2000, p. 7) and although it must have been a daunting prospect for a twenty-three year old from a comparably provincial Rome, he quickly seized upon its many opportunities. He became good friends with Amedeo Modigliani and the artists of what would come to be known as the Ecole de Paris and immersed himself in the capital’s cultural circles. It was during this period that he came into contact with the doctor Pierre Declide and accepted an invitation to stay at his home in Civray in Western France. Severini stayed for three months, enjoying the change from city life and taking full advantage of the new subjects this setting provided.

Paesaggio di Civray dates from this visit and shows Severini tackling a serene landscape on a large scale. Art historian Piero Pacini describes the present painting as “the most significant work from his stay in Poitou [...] to be compared to some of the landscapes Seurat painted between 1880 and 1890. It constitutes a spontaneous, emotional encounter with a restful, natural but surprise-filled environment” (quoted in Exh. Cat., Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, De Fra Angelico à Bonnard, Chefs-d'œuvre de la Collection Rau, 2000-01, p. 202). Severini may have been inspired in this endeavour by the work of his Italian contemporaries including Giacomo Balla, who he had met through Umberto Boccioni not long before leaving for France. Balla was simultaneously working on a major commission for the Villa Borghese (fig. 1) and knowledge of that may have encouraged Severini in a similarly grand undertaking for the present work.

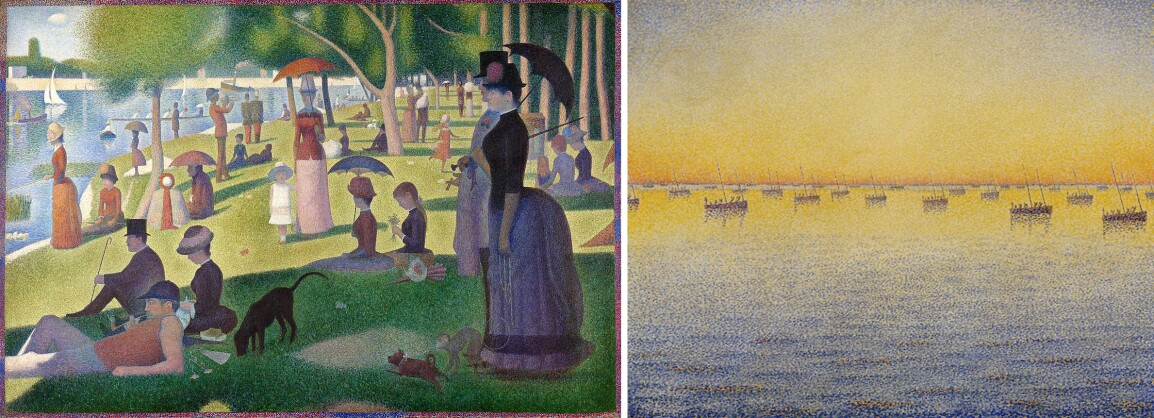

Right: Fig. 3, Paul Signac, Concarneau. Pêche à la sardine, 1891, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

However, stylistically speaking by far the most important influence on the young artist at this stage were the works he had been surrounded by in Paris. Although aware of the more recent developments of Fauvism, he made it clear that his focus was elsewhere: “I did not object at all to such explorations, nor did I consider them remote. Matisse may have already started to work in that direction, but I did not meet him or begin to appreciate his ideas until much later. I was interested in achieving creative freedom, style that I could express with Seurat’s and the Neo-Impressionists’ colour technique, but shaped to my own needs” (Gino Severini, The Life of a Painter: The Autobiography of Gino Severini, Princeton, 1995, p. 53).

“A veritable colour poem that gave the most ordinary landscape a definitive, grandiose expression.”

Severini’s interest in Divisionism and colour theory is fully realised in the present work. Applying dashes of pure colour he works them up in layers to create an abundant, vivid rural landscape that recalls the pioneering colour work of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac (figs. 2-3). Seurat’s use of the Golden Section as a means of ordering his compositions was also of real interest to Severini and again, the elegant, balanced proportions of Paesaggio di Civray seem to reflect this. The result is a landscape of almost classical harmony - stretching into the distance and bathed in a rich golden light, it is both inviting and powerfully evocative.

Although the tranquility of Paesaggio di Civray is far removed from the frenzied energy of the Futurist style that Severini would adopt only a year later, the overarching ambition and vision would endure. When the Manifesto of Futurist Painters was published in February 1910 it signalled a departure for Severini and his contemporaries - from then on they would be singularly devoted to a depiction of modern life characterised by “universal dynamism”. Yet, Severini would continue to use the same staccato brushstrokes (now an indicator of speed as much as a diffusion of light) and in works like Le Boulevard of 1911 (fig. 4) there are traces of the same balanced perspective that make the present work so successful. With very few of Severini's early landscapes surviving, Paesaggio di Civray offers a rare insight into this key formative period in the artist's career.