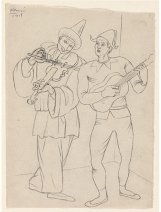

With their fantastical costumes and exaggerated pantomime, the figures of the Commedia dell’arte provided Picasso with a theme to which the artist would continually return throughout his long and prolific career. Picasso was particularly captivated by the characters of the Harlequin and the Pierrot, both of whom reminded Picasso of French saltimbanques (see fig. 1).

Executed in 1917, Pierrot reflects a pivotal moment in the artist’s career. Despite the turmoil and political upheaval triggered by the great war, Picasso was engaged in a variety of artistic projects, working with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and balancing a more naturalistic style—as championed in the present work—alongside his cubist developments. Pierrot recalls Picasso’s enduring love for theater, whilst inviting reflection during uncertain times. Delineated using soft and feathery strokes of ink, Pierrot is a beautifully executed and poignant portrait that recalls the artist’s early love of performance, while adopting a style that anticipates his later Neoclassical period.

Picasso began featuring the stock characters of the Commedia dell’arte as early as 1901, when he painted Les Deux Saltimbanques and Arlequin accoudé (see fig. 2). It was, however, during a trip to Italy in the spring of 1917 that the artist’s interest in the creative possibilities afforded by this subject was reignited. Picasso traveled to Italy alongside Jean Cocteau, Serge de Diaghilev, Léonide Massine and Igor Stravinsky. Together the group were working on the ballet Parade, but it was while exploring the ancient cities of Naples and Pompeii that a vision for a new ballet came into being, for which Picasso would design the sets and costumes. Stravinsky’s Pulcinella was directly inspired by the Commedia dell’arte performances to which the group was exposed. It was, therefore, in this state of creative fervor that Picasso returned to France to embark upon a series of drawings that would culminate in a number of large scale works—to which the present Pierrot belongs—that take the figures from the Commedia as their sole focus.

Picasso took great joy in depicting Pierrots and Harlequins, confusing their roles to suit his compositional needs. While some bear the influence of his friend and creative associate Léonide Massine, others are less instantly recognizable as they take on more universal human attributes. These traveling performers from whom Picasso initially drew inspiration, typically held a low social status, living hand to mouth as outsiders from society, a position that frequently resonated with the artist. Speaking of a similar Pierrot executed by Picasso early in 1918, Picasso scholar Josep Palau i Fabre commented: “His legendary capacity for work thus acquires one of its deepest meanings: he decants his own person, with his problems and his emotional burdens, into the work. Not through overflowing, as a romantic would have done, but through restraint of this overflowing” (J. Palau i Fabre, op. cit., p. 90). In its restrained color palette, which draws the focus to a delicate use of line and allows for the subtleties of light and expression to be felt more keenly, the same can be said of the present Pierrot. With the light falling across one side of his mouth and nose and illuminating his eyes, Picasso's figure is replete with emotional depth.

Picasso’s Pierrots

Executed on an impressive scale is, Pierrot is especially significant amid Picasso’s extensive oeuvre for its inclusion in the artist's exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1939, organized by Alfred H. Barr (see fig. 4). In the exhibition catalogue the work is noted as a study for a large 1920 oil of the same name in the museum’s permanent collection (see fig. 6). Both the oil and the work on paper present a strikingly contemplative Pierrot. Although both Pierrots are dressed in the traditional oversized white jacket and wide-brimmed conical hat of the role, their expressions offer a sadness that is both haunting and comical through the juxtaposition with their elaborate clothing.

Art historian Douglas Cooper has commented upon the artist’s keen reading of his subjects in his early theatrical pictures: “Picasso's interest in the theater as a source of paintable subject showed itself early: to be exact, in a group of paintings executed in Barcelona, Paris and Madrid between the ages of eighteen and twenty.... Picasso seems to have enjoyed the spectacle, whatever it was, for its own sake and to have relished the gay, excited atmosphere of these places of public entertainment, where he gained many insights into human nature and could find relief from the drabness of his own impoverished existence. Nevertheless, Picasso was no mere passive observer we can see from the liveliness, the intensity and the acute observation of the movements and facial expressions of the performers, which characterize these works” (D. Cooper, Picasso Theatre, New York, 1968, pp. 13-14).

As with these very early works, it is Picasso’s shrewd understanding of the human condition that is felt so strongly in the present Pierrot. Looking wistfully away from the viewer, with an expression that stands in contrast to his outfit, Picasso manipulates stock characters in order to approach a universal subject matter from conflicting viewpoints of sensitivity and humour. In a statement made by the artist in 1921, and printed in the aforementioned catalogue, Picasso stated “… it is in our subjects we keep the joy of discovery, the pleasure of the unexpected; our subject itself must be a source of interest” (Picasso: Forty Years of his Art (exhibition catalogue), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1939, p. 12).