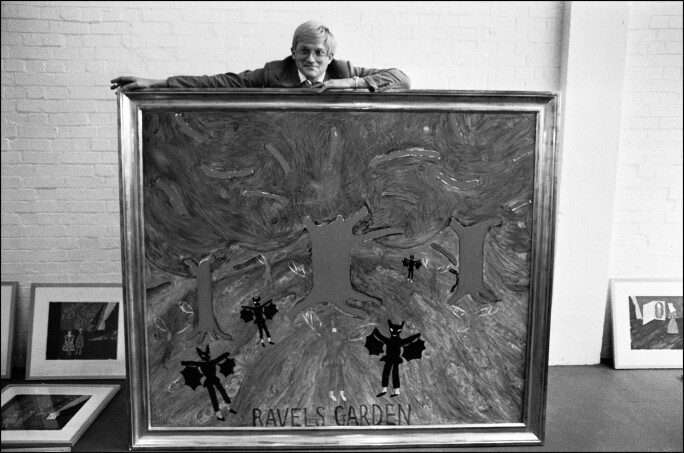

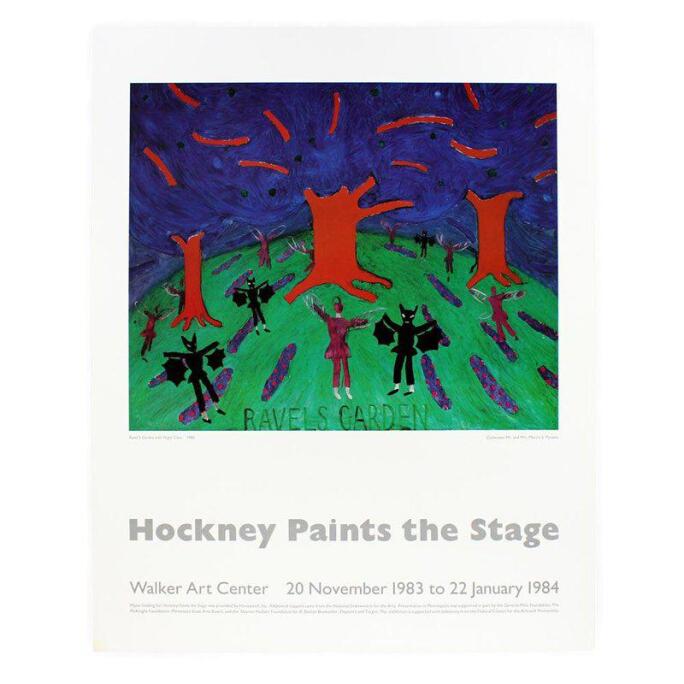

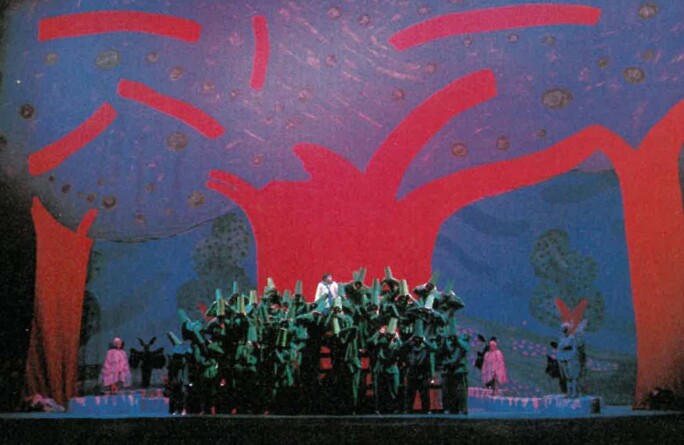

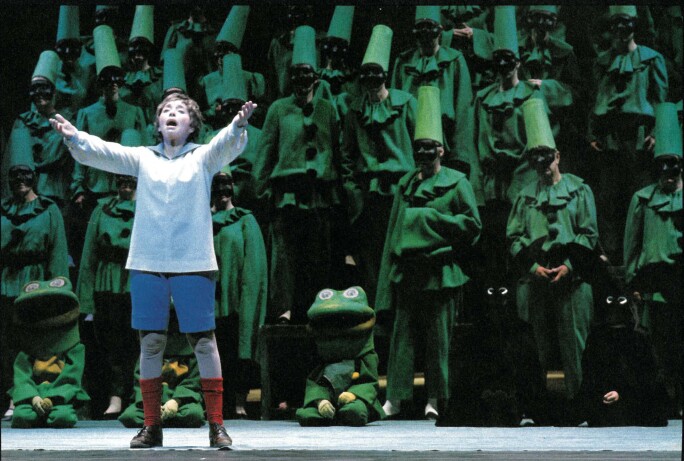

R avel’s Garden with Night Glow from 1980 is one of David Hockney’s most transcendent and deeply meaningful works depicting the jubilant final scene from Maurice Ravel’s 1925 opera L'enfant et les sortilèges. Through his iconic technique and the interplay of the colored lights, Hockney brings to life the fantastical world of his personal favorite opera, in which a rude child is reprimanded by the once inanimate objects in his room and then transported to a tree filled garden that comes alive with singing animals and plants once tortured by the child. Known for his mastery across a number of mediums, Hockney’s immersive theater designs and their correlating paintings, including the present work, mark the artist's ability to create entirely encompassing visual experiences within the confines of an otherwise two-dimensional canvas. The present work invites a multitude of senses to interact well beyond the canvas which ultimately creates an incredibly rich viewing experience. Hockney began losing his hearing in the 1980s and oftentimes has since said that his hearing loss has had an integral impact on his skill as an artist—"If you lose one sense, you gain other senses." It is through this highly personal experience and his lifelong love of the opera that the present work stands as a truly emblematic example of Hockey's ability to tap into the senses of his viewers. Throughout his oeuvre, Hockney uses vibrant color as a tool to express emotion, which adds new meaning to the visual intensity created between the canvas itself and the atmospheric glow created by the specially selected red and blue lights that truly set this work apart as one of Hockney’s most impactful paintings. Ravel’s Garden with Night Glow marks the pinnacle of Hockney’s theater paintings given his commitment elevating the all encompassing visual experience in order to create a truly thrilling sensory experience for the viewer.

“I remember when I first showed my model to John Dexter, he said, ‘We’ll light it directly with white light.’ But I said, ‘No, I’ve worked out more than that.’ When I said we should use blue and red lights on it I must admit he showed little interest, yet I felt that was how we were going to get the visual equivalents of the music. He used to joke about ‘your colored lights’ and I said, ‘Well, to my eye, it expresses the music. When you see that color, with the blue light on the huge blue mass of the tree foliage, I think you physically take the color into your body as you take in the music. You can do this in theater in a way you can’t do in the cinema, because the cinema is not quite about color, it’s about light. But where there’s physical color, pigment, it’s a different matter isn’t it? A physical color is a physical thrill.”

The present work is a vibrant revival of the opera that Colette was asked to write for a fairy ballet during World War I. In 1916, Colette carefully chose the French composer Maurice Ravel to set her text to music. In the years that followed, Ravel was met with extreme bouts of poor health only to receive the inspirational spark he needed to complete his composition after following American composer George Gershwin’s musical successes. By 1925, Colette feared that her text would never be brought to life and was overjoyed that L'enfant et les sortilèges was finally to be performed in Monte Carlo on March 21, 1925. Ravel remarked, “Our work requires an extraordinary production: the roles are numerous, and the phantasmagoria is constant. Following the principles of American operetta, dancing is continually and intimately intermingled with the action.” Ravel’s Garden with Night Glow is the summation of Hockney’s love for and transformative powers over the stage as reflected by a lifelong interest in music and theater.

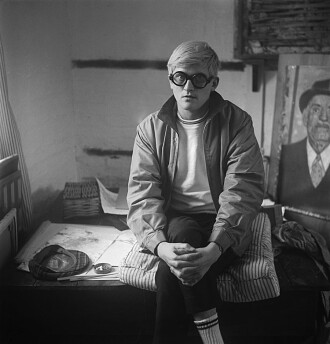

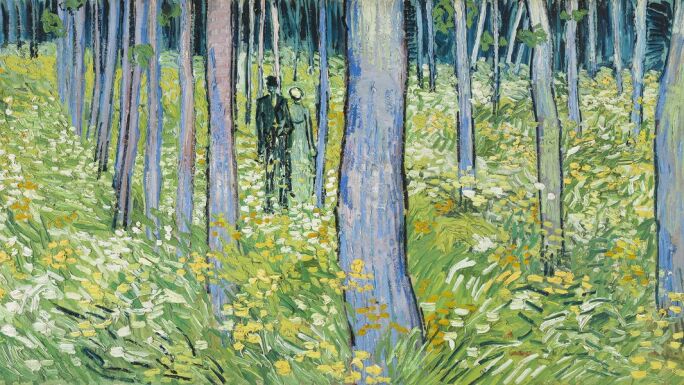

As one of the most prolific artists of our generation, David Hockney’s career is marked by his iconic mastery across various mediums. What is perhaps less known about the artist is his lifelong appreciation for music and the role it has played in the creation of many of his greatest paintings. Stephen Spender explains, “The fundamental reason for the extraordinary success of Hockney’s designs for the opera is that his passion for music is at least as great as his passion for painting. An intense and close observer, whose most constant facial expression is that of his eyes being screwed up with looking, he listens with as great intensity as he looks. He is an addict of the Sony Walkman, and with earphones over his head, walks along the pavement or drives his car or lies upon the floor of his house, listening perhaps to The Barber of Seville or perhaps The Magic Flute or perhaps to Oedipus Rex or perhaps to the music he most cherishes—Ravel’s L’Enfant” (Stephen Spender, ‘Text to Image,’ in Exh. Cat., Hockney Paints the Stage, London 1985, p. 61). The present work, Ravel’s Garden with Night Glow, encapsulates a true marriage of the arts and stands as a testament to Hockney’s lifelong commitment to creating works of art that are truly transformative and immersive. The canvas pulsates with vivid immediacy and a vivacious energy created by the swirl of Vincent van Gogh-like brushstrokes that possess the power to create a truly three dimensional space much like the Metropolitan Opera’s lively stage. It is through this deep appreciation for the artists who came before him that Hockney is able to fully embody the true artistic prowess of his creative genius.

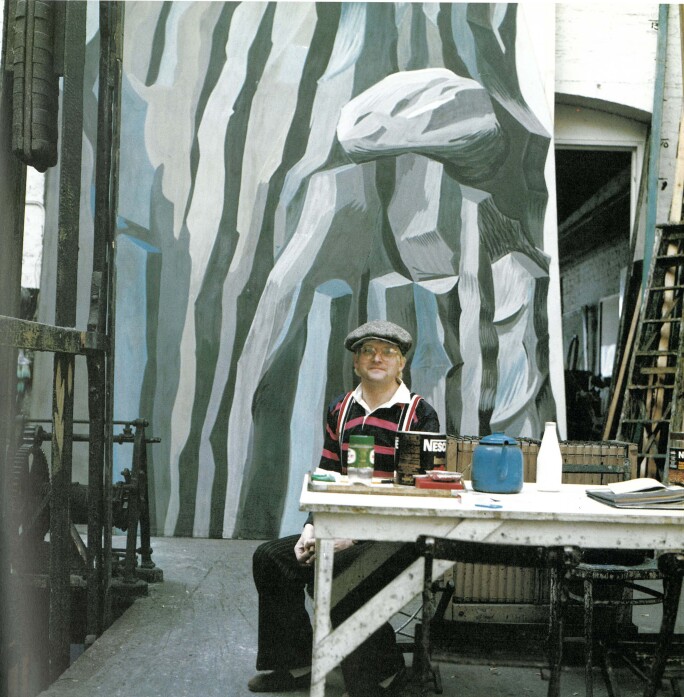

Hockney’s first exposure to designing theater sets and costumes came in 1966 under the tutelage Ian Cuthbertson for Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi at the Royal Court Theatre in London. Hockney found his work on Ubu Roi to be a near seamless transition from studio to stage, as reflected in his own words: “I had played with those ideas before and thought of all my pictures as drama. Even the way I was painted at that time was a kind of theatrical exaggeration” (David Hockney in Martin Friedman, ‘Painting into Theater’, in Exh. Cat., Hockney Paints the Stage, London 1985, p. 11). The immense success of Hockney and Dexter’s collaboration for the Met Opera opened the door to another triple bill just one year before the present work was painted. Hockney was approached by famed theatre, opera and film director John Dexter and tasked with the project of creating the set designs for the Metropolitan Opera in New York spanning the best of 20th Century French musical theater including Parade by Erik Satie, Les Mamelles de Tirésias by Francis Poulenc and finally Maurice Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortilèges. Years before, Pablo Picasso had famously designed the set for the same triple bill, which coupled with the Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art gave Hockney an abounding surge of creative energy. Hockney was flooded with inspiration and his seemingly spontaneous mark-making and textural brushstrokes employ an almost primitive energy that is deeply evocative of our childhood perceptions that bring to life Colette and Ravel’s fantastical world.

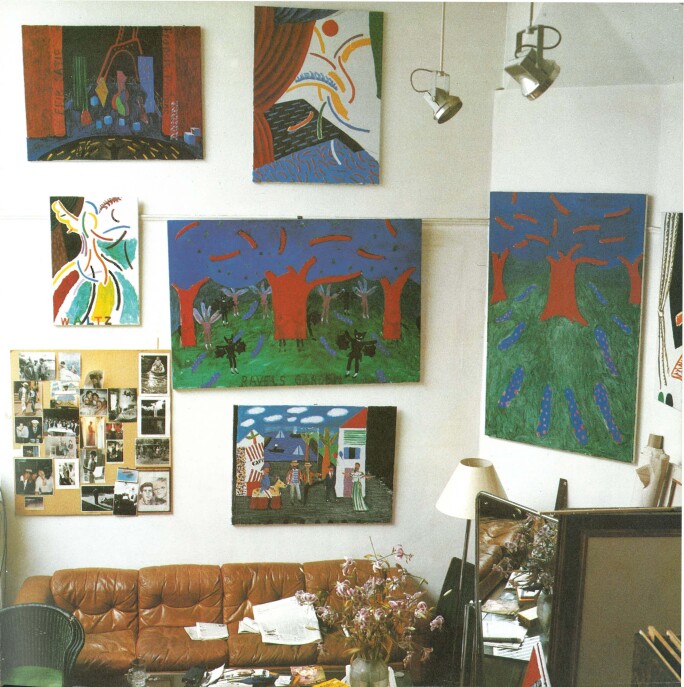

As an artist once so prominently identified with Pop related imagery, Hockney found himself exerting strong and much welcomed influence over the artistic direction of the Metropolitan Opera’s New York stage as encapsulated through each of Hockney’s highly gestural brushstrokes. In the catalogue for the Hockney Paints the Stage exhibition, Hockney remarks on the inspiration behind the present work saying “I drew the forms of the tree while listening to the garden music. When the cats finish their duet, the music goes mad, the room disappears and a great sweep of beautiful music fills the space. I drew directly on the cardboard model with a brush while listening to it. When I first began working on the garden, the trees were much smaller. At first I was thinking about a child in an intimate garden, but it suddenly dawned on me that in the child’s view, everything should be gigantic” (David Hockney in ‘Designing Parade,’ in Exh. Cat., Hockney Paints the Stage, London 1985, p. 173).

What sets this work apart from his entire oeuvre is the boundaries he pushed with the inclusion of the lights installed personally for the Pynoos family and the fact that the title reflects this very artistic vision as an integral part of the true intent and enjoyment of the painting. Hockney explained, “I always knew that moment would be magic” (David Hockney in ‘Designing Parade,’ in Exh. Cat., Hockney Paints the Stage, London 1985, p. 176). As an avid experimenter, the play between the colored lights and the royal blues of the foliage, jade greens and brilliant reds of the monumental trees within the canvas create a powerful sensory experience that celebrates the power of Hockney’s creative vision and the life his designs have given to Ravel’s magical world. Hockney’s Ravel’s Garden with Night Glow marks the ultimate symphony between one of Hockney’s most beloved operas, his phantasmagorical ability as an artist and his commitment to pushing boundaries through his ongoing artistic practice in which the viewer is invited to step into Hockney’s magnificent and vibrant world.

Throughout the time in which Hockney collaborated with Dexter on designing theater sets, the artist found himself in situations requiring constant compromise. Though he was occasionally torn between his own artistic urges and the functional needs of the theater world, Hockney nevertheless found himself “unable to resist the seductive, glittering realm of the stage, [and demonstrated] a willingness to adapt to its special demands” while keeping true to his artistic vision for each of the three operas (Martin Freidman, ‘Painting into Theatre’, in Exh. Cat., Hockney Paints the Stage, London 1985, p. 15). Hockney’s reflection on this push and pull encapsulates the very essence of the labor of love that these theater works are rooted in — as captured in his statement: “The theater world tends to think that a strong artist won’t cooperate enough—that he’s not used to such an approach and tends to do things his own way, and other people simply have to fit in with this. It’s true when you’re painting a picture you don’t really have to defer to anybody, whereas in the theater, you do. On the other hand, although I understand the need to listen to someone else’s ideas in the theater, I’m not going to do something that goes against what I think should be there” (David Hockney in Martin Friedman, ‘Painting into Theater’, in Exh. Cat., Hockney Paints the Stage, London 1985, p. 15). The present work stands as a testament to the pure artistic intent that Hockney brought to the production of Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortilèges and his commitment to each detail and carrying his vision to completion as seen in the very moving final scene.

“There was no question about Parade’s French ambience. The large, free-form blue, red and green shapes in L’Enfant’s garden scene are as evocative of Matisse as of childhood perceptions. Like the fauve painters, Hockney allowed himself to regard the world with innocent eyes. The final image of the garden scene is an enormous tree whose thick red trunk and branches are abstract shapes that vibrate against dense blue foliage. Because he “sees” music colouristically, he sought to match Ravel’s tonalities in colour in his opera design. It is as if the child-hero of L’Enfant had envisaged the garden"

To stand before Ravel’s Garden with Night Glow and experience the way in which Hockney’s vibrant use of color and vivid brushstrokes intermingle with the atmosphere created by the colored lights is an invitation into the world so fantastically created by Collete and Maurice Ravel nearly a century ago. Hockney’s handling of space and depth together possess the visual equivalent of a magnetic force of their ability to bring the viewer deeper and deeper into the canvas and thus into the garden brought to life through Ravel’s timeless compositions. As a viewer, one almost imagines him or herself as an actor onstage during the final scene in which the animals help to reunite the child with his mother. David Hockney’s ability to create such an immersive viewing experience through the sensory experience created in dialogue between the painting itself and the aura of the lights is a summation of Hockney’s decades-long artistic genius in which he brings new worlds to life through the magic of his brush. To see this work illuminated as Hockney intended and as the Pynoos family enjoyed the work for so many years is like a trip to the Metropolitan Opera—exactly how Hockney envisioned it following years spent listening to the operettas on his Sony Walkman.