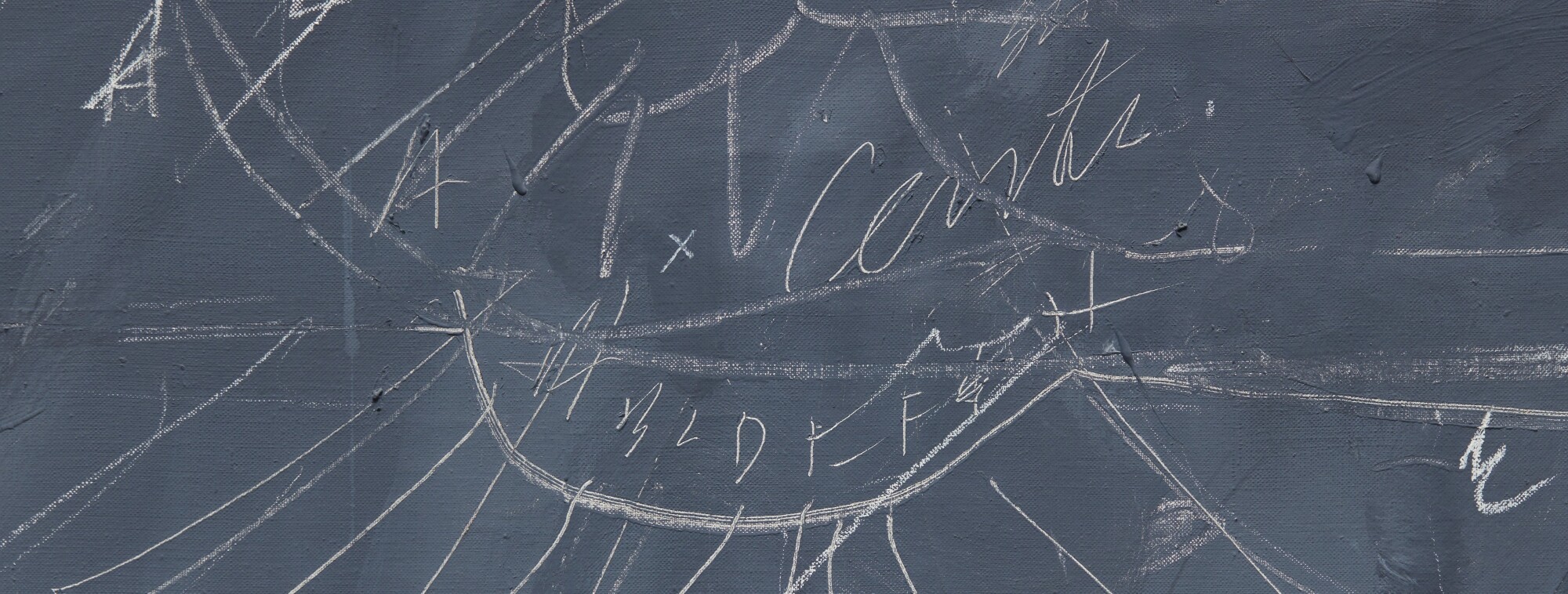

Created in 1968, amidst a period of profound inspiration and intense productivity, Synopsis of a Battle represents an intellectually rigorous yet poetically enthralling masterwork from Cy Twombly’s celebrated series of Blackboard paintings. At once calligraphic and painterly, this magnificent canvas cleverly evokes the chalklike notations of an educational lecture whilst remaining utterly illegible—an allover tapestry of quivering jots, dashes and lines. Set against its slate-gray background, the frenetic notations break free from logical understanding to declare their own autonomy. They are the heraldic symbols of an uncharted new pictorial mode that cleverly bridges the gap between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism.

Synopsis of a Battle belongs to a subset of the Blackboard paintings created between 1968 and 1970, partly inspired by Leonardo da Vinci's sketched prototype of a fighting vehicle, that seem to mimic architectural blueprints or mathematical schema. Whilst an earlier and later series, of 1966 and 1971 respectively, feature lasso-loop swirls, the present series relates to the historic battles of Alexander the Great. Another painting in the series refers to the Battle of Issus (333 BC), in which Alexander the Great defeated Darius of Persia’s much larger army. One of only five paintings bearing the same title, all painted in May and June of 1968, two of the others are found in museum collections, including The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, in Richmond, VA. The present painting has been held in The Macklowe Collection for over forty years and is further distinguished by being the only painting devoted to this theme to appear at auction in over thirty years. An enigmatic yet lyrically rendered composition, Synopsis of a Battle is positioned at the very apex of Twombly’s inimitable output.

Cy Twombly's Synopsis of a Battle Series

As in Twombly’s oeuvre as a whole, allusions to classical mythology often serve as a jumping-off point for the artist’s largely personal ruminations, adding yet another layer of meaning to an already elaborate tangle of references and allusions. “What I am trying to establish, is that Modern Art isn’t dislocated, but something with roots, tradition and continuity,” Twombly has explained. “For myself the past is the source (for all art is vitally contemporary).” (The artist quoted in Exh. Cat., Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, Cy Twombly, 2016, p. 99) However, in addition to this fixation on the past, another reference point for Twombly’s work, particularly evident in Synopsis of a Battle, derives from his fascination with advanced mathematics and the design of rocket-propelled spacecraft, popularized in newspapers, magazines and even in commemorative stamps during the ramp up to the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing. “The conical diagrams and engineering-style figures of Synopsis of a Battle uncannily resemble NASA designs and cyanotype blueprints for Gemini and Apollo spacecraft,” the esteemed British scholar Mary Jacobus has explained. “Visualizations, diagrams and photographs of space capsules proliferated during the 1960s, along with photographs of NASA scientists at their blackboards.” (Mary Jacobus, Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint, Princeton 2016, p. 117)

Twombly’s interest in advanced mathematics prefigures the Bolsena series of the following year. Twombly painted these fourteen paintings over the summer of 1969, whilst in seclusion in the Palazzo del Drago, a 16th Century Farnese palace overlooking the lake of Bolsena, about eighty miles north of Rome. The Bolsena paintings feature an array of cryptic mathematical references. “Tumbling forms, calculations and scribbled-out numbers like incorrect sums proliferate,” explained the curator Nicholas Cullinan. “[The] topic of ascent and descent is particularly applicable to the Bolsena paintings.” (Nicholas Cullinan, in Exh. Cat., London, Tate Modern (and traveling), Cy Twombly: Cycles and Seasons, 2008-09, p. 112). Indeed, Twombly painted the Bolsena group in the months following the Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20, 1969. Like Synopsis of a Battle, the Bolsena paintings correspond to the ramp-up of the Apollo launch and the scientific analysis of the sophisticated mathematical calculations required to send the spacecraft into orbit and bring it safely back to Earth.

“The conical diagrams and engineering-style figures of Synopsis of a Battle uncannily resemble NASA designs and cyanotype blueprints for Gemini and Apollo spacecraft,” the esteemed British scholar Mary Jacobus has explained. “Visualizations, diagrams and photographs of space capsules proliferated during the 1960s, along with photographs of NASA scientists at their blackboards.”

RIGHT: Jasper Johns, Map, 1962. Image © Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Art © 2022 Jasper Johns / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Twombly’s first Blackboard paintings date to 1966, at which time he began to switch over from an empty white ground to one colored in subtle gray using an oil-based house paint. Its look mimicked the appearance of an elementary-school chalkboard. While his earlier paintings and drawings on a predominately white background might feature scattered daubs of vermillion, purple or even pink, the Blackboard paintings are notably restrained. Limited to only two colors, their signature white-and-gray “chalkboard” look evokes the formal austerity of Minimalism, while still retaining the idiosyncratic touch of the artist’s hand. In the present work, the viewer is left to puzzle over the intricate arrangement of Twombly’s notations, which take the form of an outwardly expanding flowchart. Working from the top of the painting and projecting downwards, a series of diagonal lines fan outward in three separate series that become ever larger as they proceed.

Cryptic numbers and phrases are interspersed throughout. The numbers “1 thru 8” and the letters “A thru F” seem to follow a certain logic; elsewhere, letters and numbers begin to lose their comprehensibility. “A + T,” for example, and “H Σ F,” are less clear; they may indicate the abstruse equations of advanced mathematics or simply the nonsensical doodles of a child. Twombly's fondness for the elusive and cryptic was honed by his work as an Army decoder during the Korean War, and here we see him creating his own code through symbols and signs. In this as in all of Twombly’s oeuvre, the viewer wrestles with these bizarre notations. One might find meaning in some of them, but meaning is slippery, and one is never quite able to wrest it completely free from the chaos. As a result, Synopsis of a Battle courts legibility and illegibility in equal measure. Cryptically scrawled in a bewildering array that evokes both the genius outpourings of a NASA scientist or the ravings of a madman, Twombly’s canvas exemplifies the particular finesse with which he has brandished his signature Blackboard style. “Twombly's hard-to-read hand invites the viewer (sometimes tantalizingly) to decipher the meaning of his script. But deciphering is not quite right,” Mary Jacobus reminds us. Going on, she explains that Twombly’s notations depart the legible field of writing or mathematics and instead move into another realm entirely. “The effect... is like that of a musical score... Twombly's composition becomes a kind of ‘open form,’ inviting the viewer to participate in a temporal experience like that of modern music." (Mary Jacobus, op. cit., p. 51)