“There is nothing to be said: There is only to be, to live.”

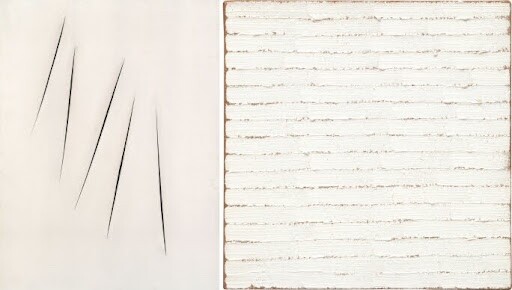

Executed in 1958, Achrome is a striking, gem-like example of Piero Manzoni’s revolutionary series of the same name—an oeuvre that came to define the artist’s radical vision and establish him as one of the most forward-thinking voices of postwar European art. A concise yet commanding example of Manzoni’s groundbreaking use of kaolin—a white porcelain clay—on canvas, the present work exemplifies his determination to strip painting of authorship, symbolism, and illusionism in favor of pure material presence. In Achrome, all narrative is silenced, all color drained, and all gestures reduced to the bare trace of a fold, allowing the elemental qualities of surface and structure to assert themselves with quiet authority.

With its intimate scale and unadorned monochrome surface, Achrome invites close, contemplative looking. The canvas has been folded horizontally, pleated with a subtle but deliberate rhythm across its width, and coated in an even layer of kaolin that both unifies and reveals the undulations beneath. The white clay, with its powdery matte finish, settles into the fabric’s topography, accentuating each compression and tension in the weave of the canvas. Light falls across these ridges and valleys, creating soft shadows and tonal shifts that animate the surface without the use of pigment. The result is a work that hovers between presence and absence, silence and eloquence.

Right: Robert Ryman, Untitled, 1965. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Art © 2025 Robert Ryman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In contrast to the gestural expressiveness of Abstract Expressionism or the emotive intensity of Art Informel, Manzoni’s Achrome deliberately evades subjectivity. Rather than asserting the hand of the artist, the work allows its materials and processes to guide the final form. In this way, Achrome aligns with contemporaneous experiments in European art that sought to neutralize the image and foreground the object, sharing affinities with the work of Yves Klein, Lucio Fontana, and the Zero Group. But whereas others reached for transcendence through dematerialization, Manzoni remained grounded in the tactility and autonomy of his materials. Here, canvas and kaolin are not vehicles for expression but are instead presented as ends in themselves—art stripped to its most elemental state.

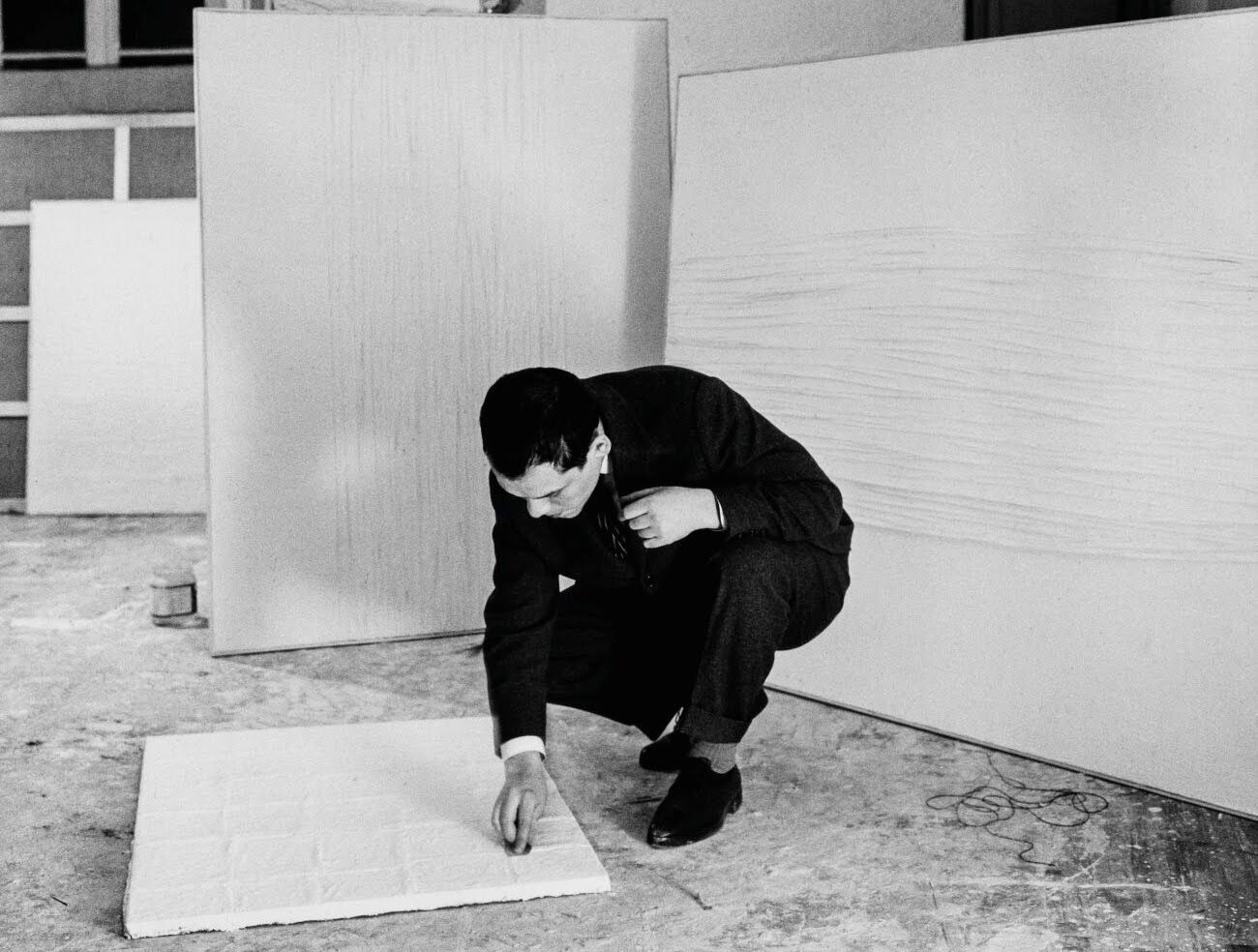

The year 1958 marks a critical turning point in Manzoni’s career. It was during this period that he began to systematically explore kaolin as a medium, recognizing in its chalky whiteness both a physical substance and a conceptual tabula rasa. Devoid of chromatic or symbolic associations, kaolin offered Manzoni a means of advancing his radical proposition: an art freed from representation, narrative, and the ego of the artist. The folds in the present work—likely formed by draping and pinning the untreated canvas before the application of kaolin—are among the most iconic of the early Achromes, a strategy he would expand upon in subsequent years through larger formats and more diverse materials, including cotton, fiberglass, and even bread rolls.

Despite its apparent austerity, Achrome is anything but static. The play of light across its surface subtly shifts with each change in angle or illumination, ensuring that no encounter with the work is ever precisely the same. This variability introduces an experiential dimension to the work, in which time and perception become part of the viewing. It is this tension—between fixity and flux, between emptiness and plenitude—that gives Achrome its enduring resonance.

Manzoni’s premature death at the age of twenty-nine cut short a career of immense promise, yet the Achrome series endures as one of the most influential contributions to postwar art. With its minimalist palette, anti-expressive stance, and radical materiality, Achrome foreshadowed the rise of Conceptualism, Arte Povera, and Minimalism in the decades that followed. The present work, executed at the inception of this trajectory, captures the clarity and audacity of Manzoni’s vision in its most distilled and potent form.