Alongside Rembrandt and Van Gogh, Munch is one of greatest self-portraitists in all art history, ruthlessly interrogating his image and identity in a series of paintings that began in 1882 when he was just eighteen and continued for the rest of his life. This masterpiece from 1926 is arguably the finest self-portrait remaining in private hands and epitomises Munch’s sustained exploration of identity, life and death and the role of man in a modern age. It is part of a journey that would transform the genre of the self-portrait, focusing on the artist-as-individual in a way that would prove deeply influential to a subsequent generation of artists who would increasingly come to see themselves and their life experiences as core subject matter for their art.

From his earliest works to the troubled years prior to his breakdown in 1908, Munch’s self-portraits were always intended to communicate a deliberate message to the viewer; Self-Portrait with Palette is no exception. By 1926 Munch had long been settled at Ekely, the estate and former market garden he had bought in 1916. There he created both indoor and outdoor studios, the latter explaining the striking outdoor setting of the present work. This new home would be of huge importance to Munch in his later life, as Elizabeth Prelinger explains: 'Ekely became for Munch what the villa and garden at Giverny meant for the Impressionist painter Claude Monet: a rich source of inspiration for his art and nourishment for his soul. Drawing upon the many vistas throughout Ekely, Munch replaced the cycle of human emotional experience - the frequent subject of his early art - with the age-old tradition of celebrating the grand cycle of life as seen through the seasons and seasonal activities. Although many of the images seem like simple depictions of simple activities, they are layered with the issues that the artist had been confronting since returning to Norway. These include the politics of subject matter and painting style' (E. Prelinger, After the Scream: The Late Paintings of Edvard Munch (exhibition catalogue), High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 2002, p. 51).

Both subject matter and painting style are addressed in the present work. The brighter palette is typical of this period, but the application of colour suggests a particular scrutiny of technique. The yellow of his mottled smock is a melody that picks up again in the house in the background and in the self-assured lines of the artist’s face. The clouds follow an undulating treeline that is purest Munch and their purples and blues find an echo in the curve of the artist’s skull and the line of his shoulders. There is a cohesiveness to the whole that speaks of an artist at the height of his powers. Discussing this work and its counterpart, painted in the same year and now in the Munchmuseet, Oslo (fig. 4), Iris Müller-Westermann writes: ‘he completed two self-portraits in the summer of 1926 in which he depicts himself full of strength and willpower. One shows him as a painter, the other as a thinker […]. The technique and bright colours of this self-portrait [the present work] reveal the continuing strength and energy of the sixty-two-year-old artist. Munch reasserts himself as a painter […]. In the context of the picture, the brushes and palette form a screen or barrier to the outside world […]. The painter can only reach the outside world with the help of his painting equipment. His roles in the ‘real’ world are marked by grave doubts. As a painter, however, and only as a painter, Munch feels strong and safe; as a painter, he can face the world’ (I. Müller-Westermann, Munch by Himself (exhibition catalogue), op. cit., p. 163).

‘I sensed an enormous energy which is largely based on his technique and execution […]. It’s all about brushstrokes, variation in thickness of paint layers and areas of ground left exposed as part of the motif. It’s about precise and sudden paint strokes […]. The technique bears witness to an eager and energetic painting process and it moves me […]. This is truly expressionism […]’

The same year that he painted Self-Portrait with Palette, Munch sent the work to the Kunsthalle Mannheim in Germany where it was exhibited before being acquired by the museum. Most of Munch’s self-portraits were not exhibited during the artist’s lifetime, they were painted not for public display but as an act of artistic introspection. That Munch chose to send this work back to Germany – the country where he had experienced his first commercial and critical successes – tells us much about both the work and Munch’s own state of mind at the time. From his earliest days when as a young and largely unknown artist he organised his first monographic exhibition, Munch had always been a clever self-publicist. Self-Portrait with Palette is an assertion of artistic confidence and was evidently intended as a direct communication to patrons and collectors in Germany.

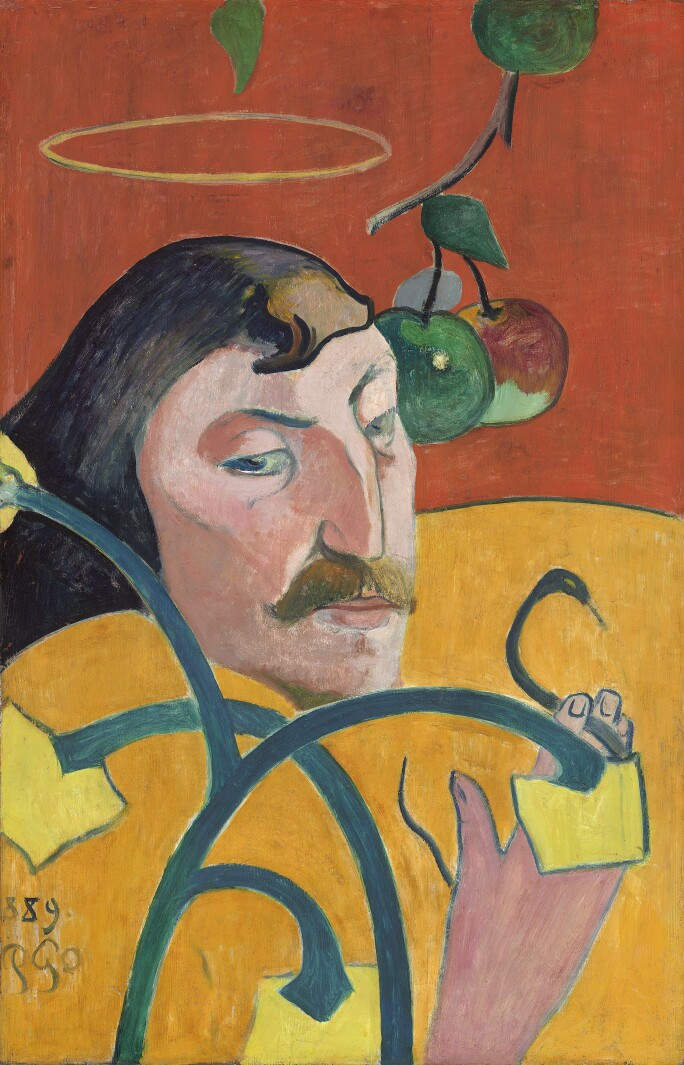

Centre: Fig. 6, Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait as Painter, 1888, oil on canvas, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Right: The present work

In so far as Self-Portrait with Palette tells us about the artist at a specific moment in time, it conforms to Munch’s use of the self-portrait throughout his career, and indeed to the role of self-portrait in art history. From Rembrandt through to the present, artists have turned to themselves as subject. Often these works were not dissimilar to the status portraits made for rich patrons; they were an act of signalling, with the artist dressed in his work clothes (fig. 5) or with palette in hand (fig. 6) announcing his profession and vision. Artists right into the twentieth century have continued this tradition and in depicting himself in this guise Munch was undoubtedly painting himself into an artistic canon that included masters such as Rembrandt, Velázquez, Fragonard and Manet. At the same time, Munch’s virtuosic technique underscores his critical role in Modern art; absorbing the experiments of Matisse and the Fauves, Munch adopted a non-naturalistic use of colour and expressionistic mark-making that then in turn had an important impact on German Expressionism. The bold and distinctive style evident in the present work acts as a reminder of his essential role in this respect. However, there was also a marked shift in the attitude towards self-portraiture around the turn of the century as artists began to use it not to show what they were, but who they were. For example, Gauguin’s self-portrait of 1889 (fig. 7) shows the artist with a halo and serpent in the garden of Eden; he envisages himself as Adam, the origin of Man – it is a bold statement of ego. If there were these murmurings of change in the 1890s, arguably it was Munch who would fully realise the potential of the self-portrait.

Bridgeman Images

His obsessive and varied exploration of the self-portrait spans all medium and provides us with countless images of the artist, tracking the experience of a single human life. His treatment of the self-portrait would inspire some artists to direct borrowings, as in Warhol’s Self-portrait with Skull (figs. 1 & 2) and his prints after Munch or Robert Mapplethorpe’s haunting self-portrait of 1988 (fig. 3). For others, his treatment of the self would open up the possibility of centering themselves at the core of their art (figs. 8 & 9). In this preoccupation with the self, Munch was ahead of his time. Sue Prideaux argued that The Scream represents a ‘portrait of the soul stripped as far from the visible as possible – the image of the reverse, the hidden side of the eyeball as Munch looked into himself […]. It has come to be seen as a painting of the dilemma of modern man, a visualisation of Nietzsche’s cry, “God is dead, and we have nothing to replace him”’ (S. Prideaux, Edvard Munch. Behind the Scream, New Haven & London, 2005, p. 151). But Nietzsche asked a further question; if God is dead and mankind killed him, ‘Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?’. The latter half of the twentieth century has made his remark seem prescient. As access to cameras has become ubiquitous we have become our own artists, with ourselves as subject and our lives captured from cradle to grave. We have entered a new age of the self and Munch was there before us all.

As part of the Kunsthalle Mannheim’s collection, Self-Portrait with Palette was included in a number of major Munch exhibitions in the late 1920s and early 1930s. However, in 1937 as Munch’s art was declared degenerate by the Nazi propaganda ministry, the work was deaccessioned by the National Socialist government. It was bought by Harald Horst Halvorsen who along with a number of Munch’s other friends and supporters were trying to recover the considerable number of Munchs that had been in German museum collections and were at risk of being destroyed by the Nazis. When Halvorsen sold it at auction in 1939 it was purchased by Thomas Olsen. Olsen was a friend and neighbour of Munch’s in Norway, and with the artist’s encouragement was instrumental in the rescue of many of his works from Nazi Germany. He built one of the most important private collections of Munch’s work, including this self-portrait which has been with his family ever since. It has been widely exhibited including in the seminal exploration of Munch’s self-portraits Munch by himself held at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Munchmuseet, Oslo and Royal Academy of Arts, London in 2005.