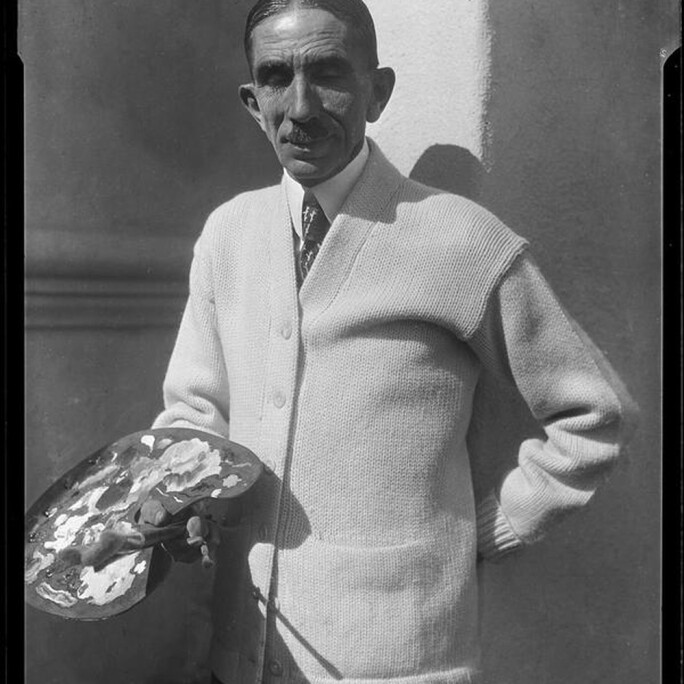

Alfredo Ramos Martínez came from humble beginnings to become one of the foremost figures in Mexican twentieth-century modernism. Born in Monterrey, Mexico in 1871, he showed artistic promise from a very early age, winning a scholarship to study at the Academia San Carlos in Mexico City at age fourteen. One of the Academia’s top students, he was commissioned in 1899 to decorate a set of hand-painted menus for a dinner hosted by Mexican president Porfirio Díaz for Phoebe Apperson Hearst (mother of the American publishing magnate). Hearst was taken with Ramos Martínez’s designs and offered on the spot to sponsor the artist to live and study in Paris. Later that year, Ramos Martínez was plunged into the artistic hotbed of bohemian Europe. He was quickly immersed by his friend, Modernist poet Ruben Darío, within Paris’ avant-garde circles, frequented by characters ranging from artists Claude Monet and Henri Matisse to the Symbolist poets Paul Verlaine and Remy de Gourmont. In 1905 Ramos Martínez began to show at the Salon d’Automne and in 1906, he won its gold medal.

He was called back to Mexico in 1909 as the Mexican Revolution broke out; immediately afterwards, Ramos Martínez was appointed director of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes under the new populist administration, and he established a series of ‘Aire Libre’ (Open Air) schools of painting in which he pioneered new methods of art pedagogy based in open-ended, outdoor artistic expression, free to all students. Ramos Martínez’s return to post-revolutionary Mexico had critical consequences for his artistic production. Abandoning the Rococo-esque scenes of his European years, Ramos Martínez’s approach became direct, powerful and thoroughly modern. His works on newspaper and canvas were marked by heavy, intentional lines and textural patterning, a dramatically flattened picture plane and a collage-like overlapping of compositional elements. Ramos Martínez’s philosophy regarding subject matter was likewise deeply affected by the revolution; motivated by waves of nationalism and anti-European sentiment sweeping Mexico City, he (like his contemporary Diego Rivera) dove into study of pre-Columbian art and history, and devoted his work to themes from the daily lives of Mexico’s indigenous people. He taught his students, “Our Mexico does not have to be tired… What the Indian does today is a marvel of significant expression, containing forms, lines, colors composed and handled without any other factor than a continuation of that superb artistic past, precolonial, never surpassed…the marvel of the simple, direct expression that Europe seeks today in its cultivated men and that we never abandoned” (quoted in George R. Small, Ramos Martínez, His Life & Art, Westlake Village, 1975, p. 81).

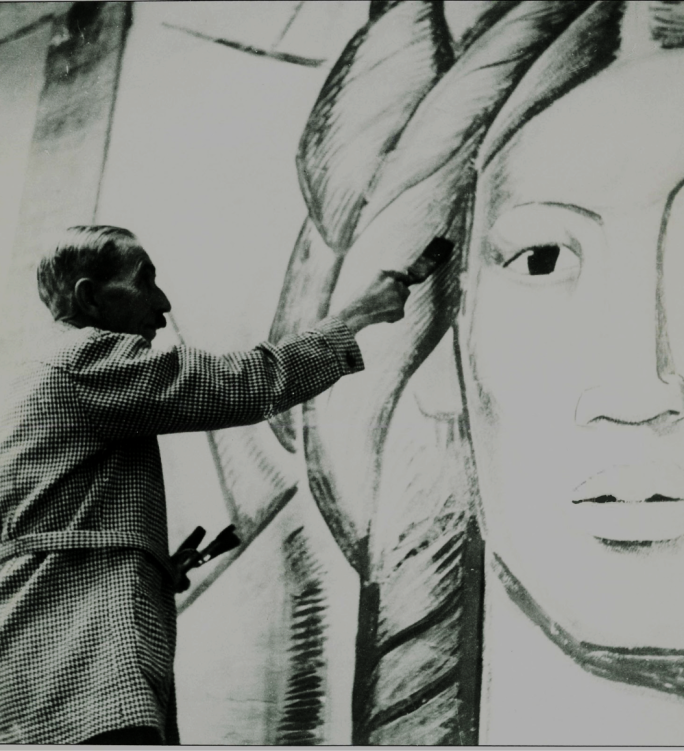

In 1929, Ramos Martínez faced two radical changes: his infant daughter María’s diagnosis with a rare bone disorder, and a subsequent move to Los Angeles recommended by her doctors. moved his young family to Los Angeles, where the climate was better suited to his ailing infant daughter María’s needs. Immersed in a foreign and rapidly changing environment, he found professional aid in his friendship with William Alanson Bryan, director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, who had known and admired the artist since his work was included in the 1925 Pan American Exhibition in New York, and quickly connected him with the flourishing artistic community there. Ramos Martínez’s images of beautiful indigenous women and tropical flora were popular with Los Angeles’ artistic crowd, paralleling the rise in popularity of Latin American-themed stories in Golden-Age Hollywood as actors like Dolores del Río, Carmen Miranda and Ramón Navarro became increasingly famous through the late 1920s and early 1930s. The nostalgic and lyrical quality of his paintings of this time appealed to Californians’ modern sensibilities, their style rooted in the present while the imagery harkened to an imagined simpler, more beautiful world “across the border.” Many of Mexico’s most important artists visited and worked in Los Angeles during these years, including Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, the latter two executing major mural commissions in this period that would have lasting influence on young American artists. Ramos Martínez likewise accepted mural and painting commissions from regional public organizations; María entre las flores shortly predates his renowned murals at Scripps College near Los Angeles, which can still be seen there today.

Kneeling against a backdrop of gently waving banana palm fronds, María entre las flores holds aloft a basket filled with jewel-toned hibiscus. The rich royal blues of her striped skirt offset the bright whites of the potted flowers behind her, acting as a foil for her rich, terra-cotta skin. A few key characteristics mark María entre las flores as a particularly special work within Ramos Martinez’s oeuvre. His subjects often gaze directly out of the picture plane with a transfixing power; here, María’s wistful, captivating glance falls just beyond the viewer’s shoulder. She kneels not amongst a forest, as his figures often do, but in a backyard garden. The attentively rendered wood paneling of a garden shed, sweet geometric earthen flower pots and softly cascading hibiscus vines contribute to the intimate domesticity of the scene. Similarly unusual is the title of the work, not an anonymous figure but María, the same name as the artist’s ailing infant daughter. Painted during a period of difficult transition from the life he knew in Mexico and marked by worry for his daughter’s future, María entre las flores may offer an imagined vision of her as a young woman, placidly gathering flowers to bring home to her family.

Ramos Martínez’s work of this period is often compared with Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings, not only for their similar subject matter but for both artists’ drive to conjure emotional states in the viewer driven by symbols and signs, rather than by a realistic depiction of nature, seeking to find ‘imagination signs and plastic equivalents capable of reproducing those emotions or states of mind without necessarily having to furnish a copy of the initial sight” (ibid., p.124). However, where Gauguin’s Tahitian women like the subject of Nafea faa ipoipo (see fig. 1), ooze sensuality, representing an eroticized and mysterious Other, Ramos Martínez’s figures are architectural and in the case of María, independent, built along an ascetic and sacred geometry. Unlike Gauguin, Ramos Martínez mined his own native culture and history for spiritual resonance. His sensibility can be related at once to Giotto’s (see fig. 2), driven by a divine inspiration to portray ideally proportioned human forms as well as to the geometric order underlying much pre-Columbian sculpture. María here does not entice us to enter a sensuous world of lush idylls; she presents a pure vision of a timeless Mexico, where modernist sensibilities echo against ancient forms. Her kneeling posture and hand holding the overflowing basket of hibiscus, tilted at nearly a right angle and overlapping flatly against the palm fronds behind her, is a clear visual reference to visual conventions of pre-Columbian art, in particular Veracruz stone sculpture.

Ramos Martínez’s ruthless reduction of forms and exceptionally careful arrangement of them into harmoniously balanced and heavily drawn compositions “reveals the influence of cubism percolating through Picasso, Léger, Braque, and others from 1908 on” (ibid., p. 131). However, unlike these artists, Ramos Martínez’s geometry was built upon a spiritual motivation closer akin to Gauguin’s drive to uncover emotional truth through evocative symbols. In the pre-Columbian sculpture he loved, geometric elements are not pure forms detached from meaning; “The Aztec pyramids, spheres, cubes and cones, far from retaining, as did the cubist ones, a whiff of classroom dampness, were cogs, pistons, and ball bearings that one suspected had cosmic functions.” (Jean Charlot, quoted in George Smalls, ibid., p. 136) The stillness of forms creates a meditative silence, beckoning the viewer to contemplate their Arcadian beauty.

The simplicity of Ramos Martínez’s forms belies the extraordinary complexity of his color. The soft golden warmth of the hibiscus and textural vibrations of the figure’s azure and white garments against the richly patterned backdrop elevate María entre las flores out of the mundane into a world of pure beauty. These jewel-like colors and evocative patterns are chosen not only for their visual effects but for their evocative qualities, the contrast of blue and white conjuring classical Western depictions of the Virgin Mary while the rich green of the leaves recalls jade, a deeply revered material for the Olmec and Mayan cultures symbolically associated with the eternal cycle of life and death. Ramos Martínez draws on the deep psychic sonority of the colors and images in María entre las flores to transport us to a transcendent plane, marked by peace and domestic bliss.