In Untitled, executed in 1984, Albert Oehlen presents a vision both blunt and evasive. The face of an owl, rendered with gestural heft, looms from a wall-like backdrop, its eyes void, its beak diamond-cut and inert. The subject hovers between form and collapse, image and refusal. This ambiguity is not an accident of expression, but a calculated rejection of clarity.

Painted at a moment when Oehlen was actively unlearning the conventions of painting, the work sits at the crossroads of figuration and abstraction that shaped much of his early 1980s practice. It is a period that resists tidy classification. While the Spiegelbilder would occupy him from 1982 to 1990, this canvas is not of that series. Yet it shares the series’ combative spirit, its determination to obstruct rather than illuminate. “This mirror idea allowed me to make an ‘original’ invention, but one that is bearable because it is so hackneyed” (The artist quoted in: Sean O’Hagan, Albert Oehlen: The Change Artist, 15 May 2015, online). A statement equally applicable to the owl, a motif freighted with cultural symbolism and yet rendered here with unceremonious detachment.

There is nothing ornamental about the execution. The paint, scraped and laid thick in parts, is not decorative but aggressive. Colour appears as residue rather than decision in tones of muted browns, greys and gold. “I had always used color - but not with my heart, my eye, or my aesthetic judgment,” Oehlen recalled. “I just didn’t care about color, and I was happy not to think about it” (The artist quoted in: Sean O’Hagan, Albert Oehlen: The Change Artist, 15 May 2015, online). The indifference is palpable in Ohne Titel, where chromatic harmony is avoided in favour of a palette that feels unearthed rather than selected.

If the composition suggests a creature, it does so reluctantly. The suggestion of an owl is barely sustained. The large, hollow circles that imply eyes are neither emotive nor inviting; they are pits. The diamond-form beak sits like an architectural intrusion. Around these features, the canvas is alive with agitation, as though the act of painting were less about depiction than about unmasking the act itself. “I put a lot of labor into making paintings that do not make sense to some and may appear ugly to others,” Oehlen says. “But really, what is ugly?” (The artist quoted in: Sean O’Hagan, Albert Oehlen: The Change Artist, 15 May 2015, online).

“A lot of people are looking for the intensity of my work or the struggle of the artist or some deeper meaning. I’m trying to get away from meaning. I don’t mean anything; I just do something.”

This embrace of dissonance was not simply stylistic, but philosophical. In the early 1980s, Oehlen, alongside Martin Kippenberger and Werner Büttner, aligned himself with the so-called Junge Wilde - an informal group of artists determined to challenge ideas of taste, mastery, and artistic seriousness. The group saw painting not as a revivalist gesture but as a field open to demolition. “Painting is impure,” Philip Guston once wrote (Philip Guston quoted in: Clark Coolidge, ‘From Panel at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art’ in Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, p. 31.). Oehlen challenged that idea by pushing it to its most extreme limits.

Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

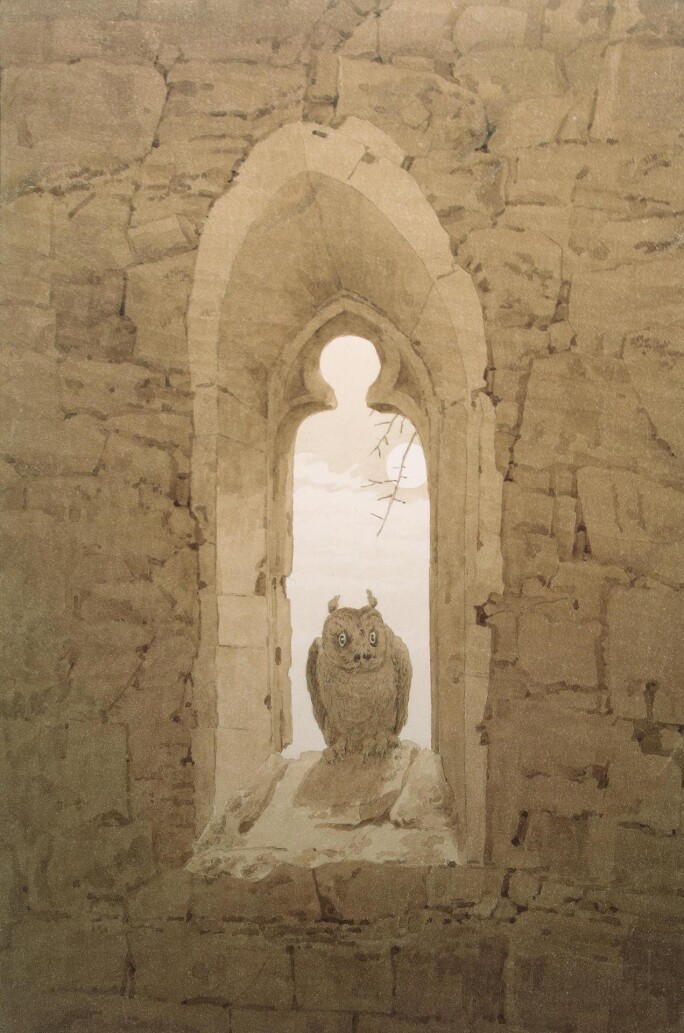

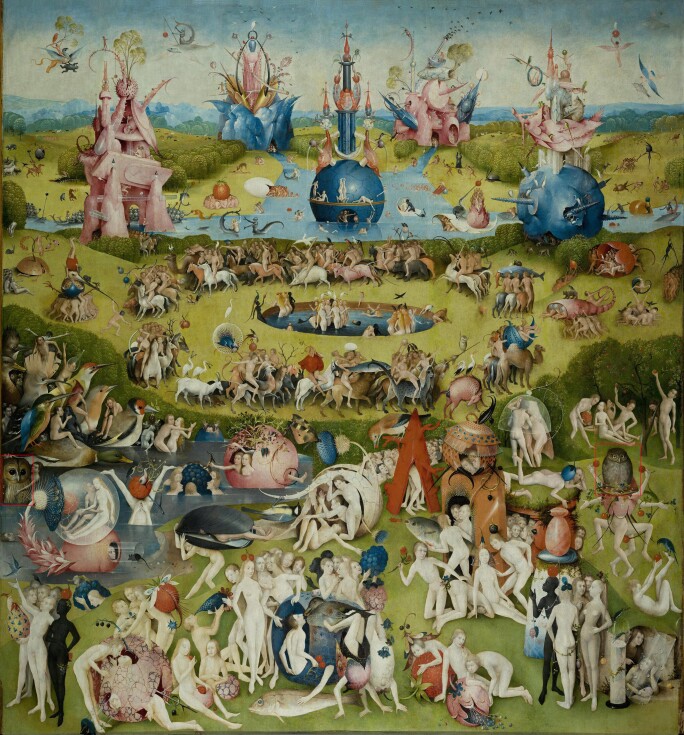

Oehlen’s rebellion was often waged through self-imposed constraints. He set himself rules in order to break them. He made deliberately ugly paintings, then asked what ugliness meant. He paired abstraction with figuration, not to harmonise them, but to provoke their friction. The owl, a symbol of wisdom since antiquity, has long been used in European art to evoke themes of knowledge, night, and introspection. In Albrecht Dürer’s The Owl in a Gothic Window (c.1500), the creature perches as a quiet, melancholic observer, while in Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (c.1490–1500), an owl lurks ominously amid chaos, often interpreted as a sign of hidden truth or even deceit. Oehlen’s owl, by contrast, is emptied of those allegorical depths. He lifts the motif from the lexicon of cultural meaning and returns it as a blunt icon, hollow-eyed and unmoored.

Museo del Prado, Madrid

Yet Untitled is not apolitical. The decision to paint like this in West Germany in the early 1980s was itself a provocation. Neo-Expressionism was ascendant, its muscular figuration dominating the critical discourse. Oehlen’s response was to parody its excesses while absorbing its scale. He painted large because Polke had not. “I was thinking, How can I go one stage further? How can I be even more free?” he said, viewing his opposition as a generative force (The artist quoted in: Sean O’Hagan, Albert Oehlen: The Change Artist, 15 May 2015, online). The freedom he sought was not liberation from history, but freedom from having to resolve it.

Untitled is a rare and illuminating example of Oehlen’s transition into what would become his lifelong interrogation of painting itself. It sits at the fault line of several movements - postmodern pastiche, Neo-Expressionism, Conceptual subversion - but it never lands squarely in any of them. Its power lies in its refusal to cohere. What remains is not an image, but a gesture. Not a painting of an owl, but a painting of the impossibility of painting an owl.